Executive summary

-

There is an extensive body of evidence suggesting that low managerial quality and poor people management practice is a key part of the UK's productivity puzzle, particularly in smaller organisations. Managers often lack the skills and confidence to prevent, contain and resolve problems at work. In total, Acas research has estimated that workplace conflict costs UK business around £30 billion per year (Saundry and Urwin, 2021).

-

The Skilled Managers Productive Workplaces research programme aimed to explore this issue and assess whether an online training intervention designed to provide managers with the skills they need to handle complex and difficult workplace issues could start to address this problem, by building conflict confidence and competence. The research involved a robust ESRC-funded randomised controlled trial (RCT) in 24 organisations, and a 'before and after' evaluation in 38 small and micro organisations funded by Acas. More than 1,000 managers and 7,000 staff took part in the programme.

-

The research revealed that managers entered the programme with relatively 'collaborative/problem solving' conflict management styles. However, there was also evidence of 'avoidant' approaches to conflict management. Experienced managers were more likely to have problem-solving styles and less likely to avoid conflict. Female managers were less likely to be avoidant/competing, but this seems driven by a greater likelihood that they were in organisations where managers in general were less likely to adopt these approaches. This reflects our general finding that organisational effects are particularly important in shaping managerial styles, consistent with studies that suggest persistent differences in management practice across organisations help explain productivity differences.

-

There was strong evidence that the Skilled Managers training had a positive impact on managers' confidence in handling conflict. Average avoidant scores reduced by 17% in the main sample, and by 22% among managers in micro/small organisations; and nearly half of managers in the main sample (47%) and 64% of those working in micro/small organisations had less avoidant conflict management styles after training. In addition, 7 out of 10 managers across the programme adopted a more problem-solving approach to conflict. However, this effect appeared to be greater in smaller organisations, where there was clear support from organisational leaders, and in those organisations in which HR had good relations with managers. This points to the importance of culture and context in enhancing or limiting the impact of the training intervention on managerial approaches.

-

Feedback from managers indicated high levels of satisfaction with the training. Managers cited the level of interactivity, accessibility and flexibility that allowed them to fit training around existing work pressures. In micro/small organisations, 8 out of 10 managers intended to change the way they managed as a result of the training, and 4 out of 10 had already put learning into practice by the time they finished the training.

-

In 14 of 24 organisations in the RCT study, staff reported a relative improvement in their support for the statement that, 'If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly'; compared to any change among staff of managers who did not receive training. There were also changes that suggest positive impacts on work-related stress; relative improvements in the 'net promoter score' (a measure of company loyalty that looks at people's likelihood of recommending their organisation) and the extent to which staff feel the organisation respects individual differences. In micro/small organisations, there were post-training improvements in engagement survey scores across a range of measures, particularly relating to performance and timely intervention in conflict.

-

Positive impacts were more likely where there was visible organisational support for managers completing the training and where there was a high degree of connection between the HR function and line managers. There was also evidence of 'spillover effects' in some organisations where elements of learning had been shared with managers in the control group or used for additional training and coaching.

-

Interventions such as Skilled Managers have the potential to extend training access to 'hard-to reach' managers, particularly those in smaller organisations. By making training available to the entire managerial team in the same period, Skilled Managers offers an opportunity to have a positive impact on the culture of conflict management in organisations. However, the intervention is not a panacea, and more holistic and long-term approaches may be needed in certain contexts to embed and sustain change.

-

The research also pointed to the potential of new technology to make people management training more flexible and interactive. It also offers opportunities to integrate skills development with organisational support, guidance and advice. Skilled Managers provides government with a possible evidence-based blueprint for making high quality training and advice available to UK managers at scale and low cost.

1. Introduction

This report considers key findings of two projects from the Skilled Managers Productive Workplaces research programme (see endnote 1). The programme involved development and testing of an online skills intervention (Skilled Managers) designed to boost managers' conflict confidence and competence; and explored the relationship between managerial capability and the management of workplace conflict. We draw together key findings from the research to answer the following questions.

a) What are the conflict management styles of managers, and how are these shaped by key contextual and demographic factors?

b) What is the impact of the Skilled Managers intervention on conflict management style?

c) Does the Skilled Managers intervention fulfil the needs of line managers and what are the wider lessons from this?

d) How does the Skilled Managers intervention impact on managerial practice and staff experience, and what can explain any variations across organisations?

e) What are the main implications of the Skilled Managers research for workplace practice and the role of Acas?

The first step in the Skilled Managers Productive Workplaces research programme was the development of an online training intervention, designed to provide managers with the skills they need to handle complex and difficult workplace issues. An intensive period of development and pilot testing – involving 5 organisations, 150 managers and Acas advisers – uncovered clear demand from managers for a more flexible, accessible and interactive approach to training (Neves et al, 2023). Therefore, the research team refined and distilled online content to focus on the skills needed by managers to:

- have good quality conversations

- address poor performance and misconduct

- decide how to respond to potential conflict

- resolve team-based conflict

The resulting Skilled Managers intervention used short videos, scenarios and simulations that could be completed in around 3 hours at a pace and time to suit the manager. Managers were also given access to an accompanying online toolkit to support learning, on completion of the initial course.

Project details are outlined in Table 1. The first study was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, and following the period of pilot testing, 24 organisations of varying sizes and sectors (see endnote 2) were recruited to take part. Initial interviews were conducted with senior leaders in each organisation to provide a range of contextual information. Each organisation was then divided into discrete units (based on function or location) headed by managers with several staff reports, and units were then randomly allocated to either 'treatment' (where managers received the Skilled Managers training) or 'control' (where they did not).

Following initial interviews with senior leaders in each organisation, the research process comprised 5 initial stages of mainly quantitative data collection, and a final qualitative stage with selected organisations:

- All staff across each of the 24 organisations – both treatment and control – were asked to complete a 10-item engagement survey.

- Managers in treatment units were given access to the Skilled Managers intervention.

- Before starting the intervention, managers completed a questionnaire to assess their conflict management 'style'.

- Managers were given 4 weeks to complete the course, and they were asked to complete the conflict management 'style' questionnaire again, at the end of training. They were also asked to provide feedback on their experience of the training.

- 6 months later, all staff were asked to complete the engagement survey again (see endnote 3).

- Interviews were conducted with selected organisations to shed further light on impacts and outcomes from the intervention.

Design of the study resulted in some very small or micro-organisations not taking part as they did not have discrete units that could be allocated to treatment and control. Therefore, a separate Acas-funded project was undertaken using the same research tools, focusing on Micro and Small Businesses. However, in this case all managers within the organisation were trained over the same period, with staff engagement measured before and after. Details of the two studies are summarised in Table 1.

| Project | Skilled Managers Productive Workplaces | Skilled Managers – Micro and small businesses |

|---|---|---|

| Funder | ESRC | Acas |

| Purpose | To explore the impact of training on the conflict confidence of line managers and consequent impacts on staff experience. | To explore the impact of training on the conflict confidence of line managers and consequent impacts on staff experience. |

| Design | Cluster Randomised Control Trial (RCT) (see endnote 4) | Event study – before and after comparison |

| Data collection | Data collected at all stages from 1 to 5. | Data collected at all stages from 1 to 5. |

| Sample |

|

|

2. Overview of Existing Research Evidence

- Poor management is seen as one reason for low UK productivity, particularly in smaller organisations.

- Workplace conflict creates significant productivity losses, estimated in 2021 to cost UK business £28.5 billion annually.

- Line managers play a key role in managing conflict, but low levels of skill and confidence are a barrier to effective conflict resolution.

- There is a lack of robust evidence in relation to the impact of developing the conflict management skills of UK managers.

- The Skilled Managers Productive Workplaces programme tests whether a 'light touch' conflict management training offer boosts conflict confidence and changes managerial practice.

For many years, governments and policymakers have tried to unpick the puzzle of low productivity. The poor record of the UK has often been linked to managerial capability (Productivity Institute, 2023). Research has consistently shown that managers play a key role in shaping experiences of work and staff engagement. In fact, a recent report from the Chartered Management Institute found that for most employees, their manager has a 'deep impact on…their motivation, satisfaction, and likelihood of leaving the job' (CMI, 2023). This has led some commentators to argue that improving managerial quality, in less productive areas of the economy, especially smaller and family-owned firms, is a crucial missing piece of the puzzle (Haldane, 2020; Productivity Institute, 2023).

However, the precise source of low productivity is hotly debated (Oliveira-Cunha et al, 2021) and there is also uncertainty over the exact role played by management practices (Gosnell, List, and Metcalfe, 2020).

Nonetheless, we know that workplace conflict creates significant productivity losses. A recent Acas-funded study estimated that individual conflict at work resulted in a cost to UK employers of £28.5 billion per annum (Saundry and Urwin, 2021); moreover, 4 in 10 workers experiencing conflict report reduced motivation and 56% report stress, anxiety or depression (CIPD, 2020).

Furthermore, it has long been recognised that line managers play a pivotal role in building trust, perceptions of organisational justice and worker engagement (Purcell, 2014). Line managers are most likely to be the source of conflict (CIPD, 2020:7) and, at the same time, managers are also best placed to identify, address and resolve conflict at an early point, minimising negative organisational impacts.

But it is widely acknowledged that there is a substantial skills gap among UK managers. Research conducted by the Chartered Management Institute found that four in five of those moving into management positions have no formal management or leadership training (CMI, 2023). The problem appears particularly acute in relation to the management of people (CIPD, 2020; Saundry et al, 2016).

Indeed, some commentators argue that management training tends to focus on leadership development at the expense of core operational competences needed to implement high quality management practices (Saundry et al, 2017).

More specifically, research over the last 15 to 20 years has consistently shown that line managers often lack the confidence needed to address and resolve problems at an early stage, before they start to negatively affect performance and productivity (Saundry, Fisher and Kinsey, 2022). A 2019 survey conducted by the CIPD found that fewer than half of a representative sample of employees agreed that 'if there is conflict in my team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly'.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of a deficit in the provision of the skills needed to manage conflict, there is a lack of robust data which explores whether these skills make a difference. There are studies that consider the impact of managerial interventions (Ichniowski, Shaw and Prennushi, 1997; Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007; Bloom et al, 2013, 2018), but these focus on the existence of management practices rather than the confidence and capability of managers to address and resolve people management problems. Therefore, the Skilled Managers programme was designed to start to fill this important gap.

3. What are the conflict management styles of managers?

- On average the dominant conflict management style before training was 'problem-solving'.

- The data suggest high levels of managerial 'avoidance', particularly in smaller organisations; but we also find higher levels of problem solving in the smallest (micro) organisations.

- More positive conflict management styles are linked to managerial experience.

- Organisational effects are particularly important in shaping managerial styles, consistent with studies that suggest persistent differences in management practice help explain productivity differences.

3.1 Conflict management styles

Managers were asked to complete a questionnaire at the beginning and end of the course to assess their conflict management style based on an inventory developed by Rahim (1983). The inventory measures conflict management style across five dimensions.

Problem-solving

The extent to which managers develop collaborative solutions to problems based on the mutual interests of all parties, including those of the manager themselves, and the organisation.

Obliging

This suggests a deference to demands of parties in conflict. Obliging managers tend to accommodate the wishes of parties to smooth over conflict, possibly at the expense of their own interests and needs.

Dominating/competing

The tendency of some managers to make decisions without involving staff and imposing decisions on the parties in conflict situations.

Avoiding

Refers to conflict avoidance. Managers may adopt a 'wait and see' approach rather than address issues at an early stage.

Compromising

Developing solutions by seeking compromise and working through a process of negotiation. This may involve 'splitting the difference' between the positions of parties.

Measuring conflict management style

The questionnaire contains 25 statements and managers were asked to rank these from 1 to 5, where 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree. Each question relates to one of the five dimensions of conflict management, allowing an average score (out of 5) for each style to be obtained.

In practice, the approach a manager takes is likely to include some elements of each dimension. However, it is generally accepted that successful and sustainable conflict resolution revolves around collaborative ('problem-solving') approaches (Rahim, 2002; Teague and Roche, 2012; Saundry et al, 2015) and Skilled Managers also seeks to minimise avoidant behaviours, emphasising early and informal resolution.

'Obliging', 'dominating' and 'compromising' dimensions all reflect some positive attributes such as listening, decision-making and negotiation, but problems arise if these styles become dominant.

3.2 Skilled managers? Collaborative but also avoidant

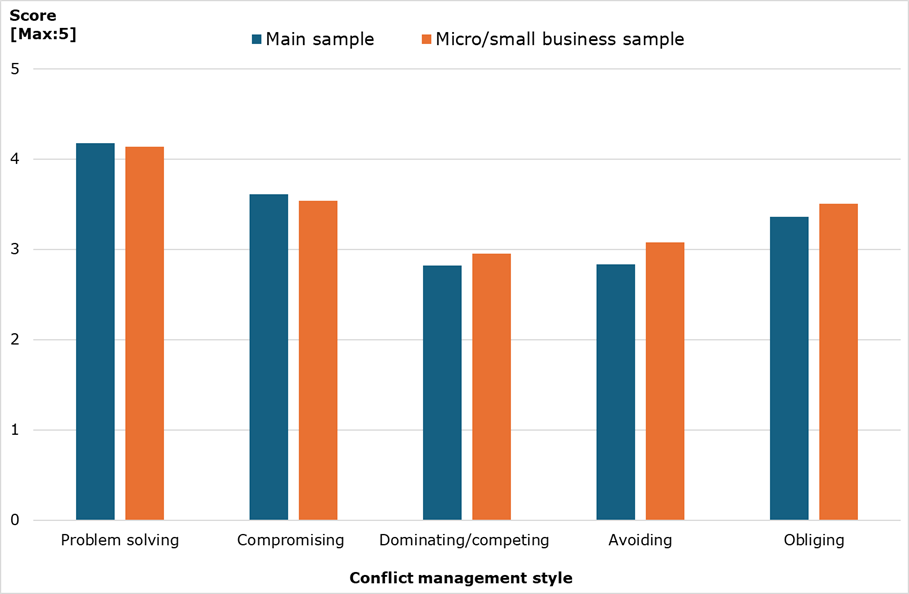

Figure 1 describes the conflict management styles of all managers in both projects within the programme, before they undertook the Skilled Managers training.

Source: Skilled Managers Rahim Inventory data, 703 manager responses Main sample and 171 Micro/small business sample (see endnote 5)

These profiles have some positive aspects, namely highest scores for 'problem-solving' and lower scores for 'obliging', 'dominating' and 'avoiding'. However, 'avoiding' scores are relatively high, particularly in micro/small-organisations; this initial picture is of lower levels of conflict competence in micro/small-organisations, with lower average 'problem-solving' and 'compromising' scores, and higher 'avoiding', 'obliging' and 'dominating' scores.

Our sample is not necessarily representative of UK organisations and whilst this finding is in line with concerns in the existing literature, we return to consider the role of company size further.

We use regression analysis (see endnote 6) to identify some of the main factors that are associated with the extent to which we see managers adopting different conflict management styles:

- There is a strong relationship between managerial experience and positive conflict management attributes. Managers with longer service were more likely to have lower 'avoiding' scores and higher 'problem-solving' scores at the start of the training.

- We found that organisational effects were important, reflecting existing literature that suggests persistent differences in management practice 'help explain…productivity differences' (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007; Bloom et al, 2013, 2019). The suggestion in our study is that some organisational environments fostered more avoidant and less problem-solving conflict management styles (see endnote 7).

- We uncovered interesting differences in the approaches of male and female managers. For instance, in our regression analysis we found that female managers are on average less likely to be avoidant, but this seems at least partly driven by a concentration of female managers in certain organisations (where managers in general are less likely to be avoidant). Similarly, in an academic study of gender differences (Bowyer et al, 2024a) female managers were less likely on average to be 'competing' than male managers, but this was again driven in some part by organisation-level factors.

Returning to our consideration of company size, the suggestion from Figure 1 is of lower levels of conflict competence in the study of micro/small organisations. When we carry out a regression analysis for the combined micro/small and main samples, the picture is more complicated.

Thus, whilst we do find that managers in small organisations [10 to <50 employees] have significantly higher average 'avoiding' inventory scores (compared to managers in larger organisations); managers in micro-organisations [fewer than 10 employees] have significantly higher average 'problem-solving' scores. Again, our sample is not necessarily representative, so we need to be careful of jumping to conclusions.

4. The impact of Skilled Managers on conflict management style

- There were significant improvements in average scores across each dimension of conflict management style following Skilled Managers training.

- Average ‘avoiding’ scores reduced by 17% in the main sample and by 22% among managers in the sample of micro/small organisations.

- Nearly half of the managers in the main sample (47%) and almost two thirds of those working in micro/small organisations (64%) were less likely to avoid conflict after completing the training.

- 71% of managers in the main study and 69% in the sample of micro/small businesses adopted a more problem-solving approach to conflict.

- We again find that variation across individual organisations provides a strong explanation – pointing to the importance of culture and context.

4.1 Transforming approaches to conflict management?

The next stage of the research was to explore the impact of Skilled Managers training on conflict management, as measured by the conflict confidence and competence of line managers (based on their pre- and post-training questionnaire responses, as described at Section 3.1). A high 'problem-solving' score is interpreted as reflecting conflict competence and a low 'avoiding' score implies confidence to address conflict (see endnote 8).

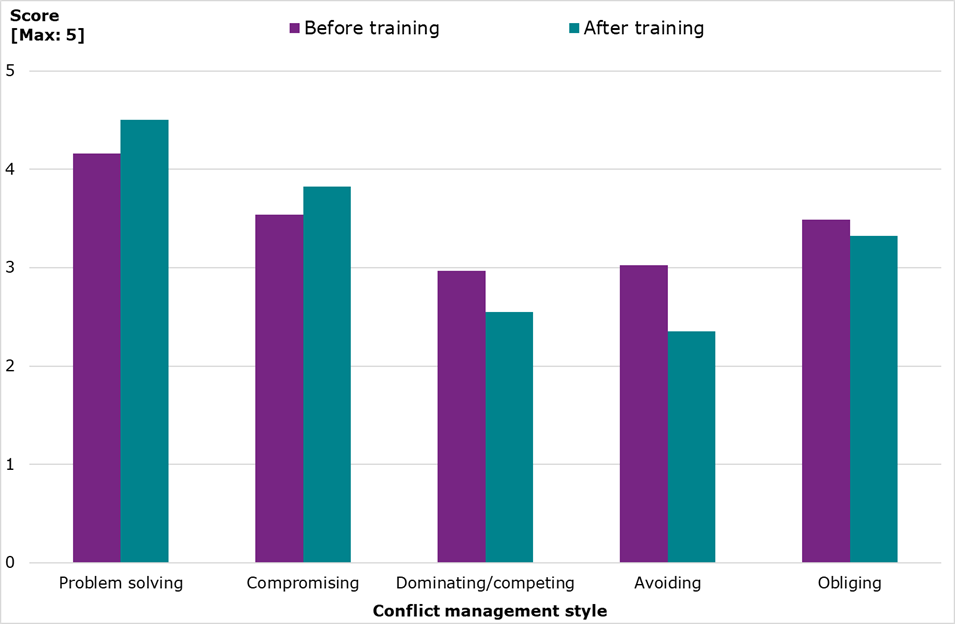

Figures 2 and 3 show the average scores of managers' conflict management styles before and after training. The results clearly demonstrate that there were positive changes across each dimension and each of these changes is statistically significant at the 1% level. There were significant increases in 'problem-solving' and 'compromising' scores and reductions in 'obliging', 'dominating' and 'avoiding' styles. Importantly the largest change was the reduction in 'avoiding' scores (by 17% for the main sample and by 22% for managers in the micro/small-business sample).

Source: Skilled Managers Rahim Inventory data Main Project, 703 manager responses Before Training and 594 After Training (see endnote 9)

Across both Figures 2 and 3 we observe a change in approaches that gives a much greater emphasis to early intervention and collaboration in managerial approaches, suggesting a positive impact by the training on conflict confidence and competence. The scale of change in average scores was larger for managers in the study of micro/small organisations than for organisations in the main project.

Regression analysis on a combined sample across both projects captures the extent to which these findings persist. Managers in small organisations [10 to 50 employees] saw the greatest improvements in terms of their move towards greater 'problem-solving' and away from 'avoiding'. However, once again variation across individual organisations provided some of the strongest explanations and we return to consider this in more detail.

Source: Skilled Managers Rahim Inventory data, 171 manager responses Before Training and 164 After Training (see endnote 10)

These findings suggest that Skilled Managers is effective in stimulating more collaborative and proactive approaches, with effects greatest in smaller organisations. Nearly half of the managers in the main sample (47%) and almost two thirds of those in the micro/small-organisation study (64%) reported being less likely to avoid conflict after completing the training. 71% of managers in the main study and 69% in the study of micro/small organisations adopted a more problem-solving approach to conflict.

5. Skilled managers: fulfilling line manager needs?

- The training was designed to provide support to managers with limited access to conflict management training and little time.

- The most common (modal) time spent on the platform was just under 3 hours, and most managers spent between 2 and 4 hours.

- However, in larger organisations there was a greater tendency for managers to spend less time on the platform.

- Feedback from managers indicated high levels of satisfaction with the intervention, highlighting its interactivity and accessibility.

- Managers emphasised the benefits of being able to fit training around existing work pressures.

- In micro/small-organisations, 8 out of 10 managers intended to change the way they manage as a result of the intervention; and 4 out of 10 had put learning into practice by the time they finished the training.

5.1 Developing the training

The Skilled Managers training was designed in an iterative process across 2021 and 2022. The starting point was to examine conventional approaches to the development of conflict management skills among managers.

The content of such training courses is relatively consistent, tending to revolve around an examination of the skills required for difficult or challenging conversations. Such courses tend to be delivered online or face-to-face across a half day or day and there is currently no experimental evidence of the impact of this type of training.

Findings from our previous research indicated (Saundry et al, 2016) that most organisations failed to provide training of this type or offered it as an optional development opportunity.

The initial versions of the Skilled Managers course were based on a full day online course, but as beta testing and piloting progressed redesigns resulted in a light touch intervention (of around 3 hours), focusing on core essential skills and providing managers with a series of micro-processes they could apply when faced with challenging situations.

In addition, accessibility and flexibility have been maximised, enabling participants to access via a tablet/smart phone using an app.

5.2 Engagement with the intervention

Between Oct 2022 and April 2023, 510 managers were invited to complete the course as part of the main study treatment group and 80% of these carried out the training. In the study of micro/small businesses, 235 managers were provided with licences and 77% carried out the training.

The most common (modal) time spent on the platform was just under 3 hours and most managers spent between 2 and 4 hours. However, once again we identify interesting differences between smaller and larger organisations. In organisations with 250 staff or fewer (in our case these are mostly micro and small organisations), 22% of managers spent less than 2 hours on the platform, whilst in larger organisations this figure is 32%.

As we shall see, this is one of several pieces of evidence raising concerns that in some larger organisations, engagement with the research and promotion of the training was less effective. There are a range of other findings that we do not have space to consider in this report, for instance the differences we observe by gender, with female managers spending on average much more time than male managers. These can be found in accompanying research publications (Bowyer et al, 2024a; 2024b) (see endnote 11).

5.3 Feedback from managers

Feedback on the training was overwhelmingly positive. A total of 621 managers from the main study (across treatment and control groups; managers in the latter were given access to the training as part of a second wave of the project) completed the feedback form; 520 responses (84%) were overtly positive with just 10 managers responding negatively to the course (see endnote 12). For many less experienced managers, the course provided new practical skills and greater confidence:

‘I found the whole course useful seeing as this is my first management role. Having never dealt with these type of situations I found the scenarios particularly helpful.'

(Manager, Social Care)

However, managers with more knowledge and experience also found the training refreshed and embedded existing practice (with some requesting more unpredictable and complex situations, particularly how to navigate legal challenges and how to manage more extreme employee responses):

'As a seasoned Manager/Senior Manager for over 25 years, I really wasn't sure that I would get much insight…. However, this was very wrong. I thoroughly enjoyed each exercise, especially the few instances where the software cited that I had provided an incorrect answer.'

(Manager, Healthcare)

A small number of managers gave a more mixed response and these tended to be senior, with 5 years or more experience in management; citing that the course was good but should be aimed at less experienced managers:

'Everything in the course were things I have already learnt in my 20 plus years of being a manager […]. I feel the course would be very helpful for people who are new to supervising and managing staff.'

(Manager, Social Care)

Respondents were positive about the overall course, with the most cited elements being the videos, scenarios and simulations:

‘I have thoroughly enjoyed the course. I have found it to be high quality, well presented and engaging. I liked the interactive scenarios and knowledge checks throughout… for me it will be helpful to have the [toolkit] at the end as I like to re-visit material and reflect.'

(Manager, Industrial)

'The course gave me space to reflect on my leadership skills. The delivery of the course and the ability to start and stop it allowed me to fit this around my diary but also factor in the unexpected being a manager in a clinical health service.'

(Manager, Social/ healthcare)

These quotes also highlight key design features of the intervention – the ability to maintain an on-going resource and source of guidance; and the ability to fit with a demanding and unpredictable work schedule. Several managers also emphasised the importance of concise, clear and straightforward messaging, focussed on practice:

'Great real-life scenarios. Info was clear and well presented. Well structured. Logical progression through different techniques. No jargon. Realistic. Not patronising/good tone. Practical application. It was better than I expected it to be.'

(Manager, Social Care)

Although the content of the course was the same for all organisations, managers working in very different contexts (Industrial, Social Care, Building contractors, Education, Healthcare and Insurance) felt that the examples reflected the challenges they faced.

5.4 Intention to change practice

There is clear evidence that the intervention created an intention on the part of managers to change their approach to management of conflict. This was evidenced through qualitative feedback in the main project. The following quote is from a manager with over a decade of experience:

'I enjoyed participating in this course as it has made me reflect on my practice, I have been a manager for a number of years and this course has made me realize that I have been stuck in my ways. I always considered myself to be competent and capable in the subjects we covered, some of which I am, and others have left me realizing its time for change and further training. I have taken notes of ways to improve my practice in the areas needed and I intend to apply them in a meaningful way…I found all the material relevant to the role I have within the team.'

(Manager, Social Care.)

Table 2 shows that 80% of managers in the micro/small study intended to change the way they managed their team and over a third had already put this learning into practice. These questions were asked in the micro/small business study to provide additional research insights, given the lack of a randomised control group - this suggests an immediate effect on practice. In the next section we consider whether this translates into action in the workplace, with a particular focus on results from the main study, where we have a more robust experimental design.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Number of managers (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Having completed the training, I intend to change the way I manage my team | 24% | 56% | 16% | 4% | 0% | 164 |

| I intend to put what I have learnt during the course into practice when the opportunity arises | 52% | 46% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 164 |

| I have already put some of the learning from Skilled Managers into practice | 13% | 26% | 42% | 17% | 2% | 164 |

Base: 180 managers carried out the training (of the 235 registered)

6. Impacts on managerial practice and staff experience

- Across most organisations, staff whose managers received the training reported a relative improvement in their agreement for the statement that, 'If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly', compared to any change among the staff of untrained managers.

- There were also changes that suggest positive impacts on work-related stress; relative improvements in the 'net promoter score' (a measure of company loyalty) and the extent to which staff feel their organisation respects individual differences.

- In the micro/small-business study there were post-intervention improvements in engagement survey scores across a range of measures, particularly relating to performance and timely intervention in conflict.

- Positive impacts were more likely where there was visible organisational support for managers completing the training and where there was a connection between the HR function and line managers.

- There was evidence of 'spillover effects' in some organisations, with elements of learning shared with managers in the control group.

- Outcomes appeared less positive in organisations where there were lower levels of trust between HR and line managers; when training had been mandated; and where there was a significant amount of organisational flux and high turnover of staff.

6.1 Did staff see improvement in early intervention and resolution?

The primary outcome measure for the main experimental study was the proportion of staff who agreed with the statement: "If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly" (on a scale with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree). This measure of manager willingness to tackle and resolve conflict reflects the main objective of the Skilled Managers training.

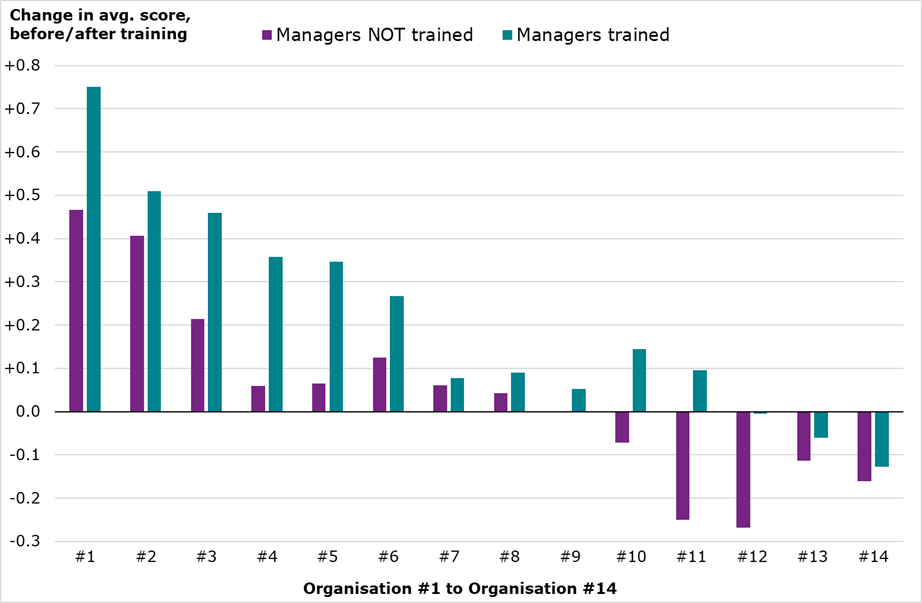

As the following discussion makes clear, in 4 of the 24 participating organisations we have evidence of positive impacts, but the experimental research design does not seem to have been followed; and 6 organisations underwent significant disruption during the period of research. Whereas Figure 4 sets out evidence that in 14 of the 24 organisations that took part in the study and the experimental design was followed, managers put lessons into practice, with the staff of trained managers more likely to agree that "If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly".

Source: Skilled Managers Engagement Survey, Main Study 2022/2023

- The green (rightmost) bars represent the change in responses to this statement, among the staff of managers who were given access to the Skilled Managers training. The change is measured from a point before the managers were trained, to a point 6 months later.

- The purple (leftmost) bars represent the change in staff responses to this statement, among the staff of managers who were not given access to the Skilled Managers training. The change is recorded over the same 6-month period.

- For instance, in Organisation 1 when staff of trained managers were asked the extent to which they agreed with the statement (with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree) before training and 6 months after, their average responses went up by just under 0.8. In contrast, in the control group the responses went up by just over 0.4. In this organisation there seems to be a general improvement in this aspect of managerial capability over the period, but the improvement among staff of managers who received the training is greater (see endnote 13).

- In contrast, across organisations 12, 13 and 14 we observe falls in average responses across all staff who responded, but the decline is less pronounced among staff whose managers were given access to the training. In these organisations there seems to be a general decline in this aspect of managerial capability over the period, but the fall among staff of managers who received the training is lessened.

A statistical test which compares the average organisation-level change for the staff of treated managers, with those of staff in the control in Figure 4, identifies a statistically significant difference (at the 10% level). Therefore, across most organisations, staff of trained managers reported a relative improvement in their manager’s willingness to intervene in a timely way to tackle conflict, and this was significantly better than any change seen among staff of managers who did not receive training. The experimental design means we have more confidence that this change is due to the Skilled Managers training.

Why did we see impacts in these 14 organisations? Several factors appear to be important. First, most organisations which experienced clear positive impacts were small to medium sized businesses where HR or L&D leads were geographically close to their managers and enjoyed high trust relationships. This helped to improve communication and build manager engagement. Second, all but one of these organisations had very limited alternative resources to fund training. This arguably created a greater demand for, and commitment to, the project. Third, it was noticeable that in this group of organisations there was a relatively high level of senior leadership support for the project.

In 4 additional organisations senior leaders ensured effective communication, co-ordination and support for staff and managers, ensuring good take up; but evidence suggests the experimental design was not followed. These organisations were enthusiastic and very positive about its impact on their managers, but enthusiasm for the training was such that they shared insights from the Skilled Managers intervention across all managers. We observed increases in the proportion of staff reporting that their managers resolved conflict quickly, in both treatment and control groups.

In 6 of the organisations there were more substantial issues, with some in crisis during the study, and/or experiencing extensive change. For example, one organisation experienced major disruption between the two surveys, acquiring a new business, resulting in job roles changing, departments being re-organised and a significant influx of new employees. This impacted the research team’s ability to differentiate treatment and control unit outcomes, and respondents reported that they felt this had a detrimental impact on staff satisfaction. Two of the organisations were large, with more fragmented structures, and there was evidence of a disconnect between HR and managers.

This study produced compelling evidence of the efficacy of Skilled Managers, but it also shows that it is not a panacea. Our research shows the importance of organisational context, and in some settings face-to-face and more holistic offers may be needed, to tackle the challenges organisations face. By giving managers the confidence to intervene earlier and resolve conflict, we can create healthy employment relationships and more productive workplaces, but one size does not fit all.

6.2 Did staff report other improvements in management practice?

We must be careful in our consideration of impacts on the other 9 items of our 10-item engagement survey (reproduced in the appendix to this report) beyond the primary indicator that "If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly". Put simply, statisticians caution that the more we attempt to find an impact using different indicators, the less confident we are about the strength of apparent impacts (see endnote 14). However, to counter this we may have some concerns over our primary indicator – specifically, if managers are more likely to intervene quickly to resolve conflict, how many of their staff would notice this and report it in feedback?

Focusing on the 14 organisations in Figure 4, responses to other parts of our 10-item engagement survey suggest three additional findings of note (see endnote 15):

- Among staff whose managers received the training, there was a statistically significant fall in support for the statement that, "I often experience work-related stress that impacts my health and job performance". This fall was not observed among the staff of managers who did not receive the training.

- We also observed a significant fall in the 'net promoter score' (a measure of company loyalty, based on the question "On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being most likely, how likely is it that you would recommend this company to a friend or family member?") among the control group, that is not seen among the staff of trained managers.

- Similarly, staff in the control group become less likely to agree with the statement "I think that my organisation respects individual differences (for example, cultures, working styles, backgrounds etc)" over the period of the study, compared to the staff of trained managers (where there is increasing agreement over the period - though not a statistically significant increase).

As our more detailed discussion in accompanying papers suggests, in some ways one may consider these findings more compelling than those impacts we uncover for our primary indicator (see endnote 16). Even adopting a cautious approach, we have compelling evidence of the efficacy of Skilled Managers.

Whilst we must note the lack of experimental design in the parallel study of micro/small businesses, before and after findings from the 10-item engagement survey in this sample are similarly encouraging:

- In the study of micro/small businesses, we observe a statistically significant improvement across many of the indicators that consider performance, such as "It's easy for me to get feedback on my performance”; “Good performance in my team is recognised" and "Talking to my line manager helps me improve my performance".

- This is in addition to significant improvements in staff reporting "If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly" (the primary outcome measure for the main study), and reinforces our findings that Skilled Managers seems particularly impactful in smaller organisations, where training all managers (and often owners and leaders) can create an organisation-wide change in managerial style and approach.

6.3 Organisational feedback – what works?

Organisations were generally positive about participating in the project and developing managerial skills that would have otherwise been difficult to embed. Follow-up interviews revealed a variety of approaches to engagement, with some organisations inviting managers to undergo the training as a benefit to themselves, but with little encouragement or 'push':

'We didn't go mandatory with it, but we set aside an expectation that you should set some time aside […] I suppose we used more of a sales pitch with it really, with what you stand to gain from it […]'

(Construction sector)

At the other end of the spectrum, organisations made completion of Skilled Managers an expectation and followed up with managers, asking to see certificates of completion or discussing conflict management scores and feedback. This approach however, received a mixed response from managers, in particular from one organisation who reported in their feedback:

'The management team weren't consulted on the use of their time, they were told they had to spend up to half a day doing this course by a certain date and that was that. This means that there is likely negativity going into this course and a reluctance to participate in full.'

(Insurance sector)

Organisations confirmed during interviews that their own feedback from managers mirrored that provided through the platform. Furthermore, some respondents reported they felt that managers were more prepared to address issues and conduct difficult conversations. For example, in one organisation HR had noticed that managers appeared to be less dependent on HR advice when dealing with relatively straightforward issues:

'Throughout this project there's definitely been an increase, I think, in manager skill set […] a little bit more of a proactive approach to managing conflict within teams.'

(Education/ Social Care Organisation)

However, there was less evidence that organisations had experienced notable impacts on team culture or performance. This points to the complexity of transmitting changes in managerial style and approach to wider organisational outcomes. It also suggests that a wider range of factors beyond conflict management may be influential.

7. Implications for policy and practice

- Interventions such as Skilled Managers have the potential to extend training access to ‘hard-to reach’ managers, particularly those in smaller organisations.

- By making training available to the entire managerial team over the same period, Skilled Managers offers an opportunity to transform organisational culture.

- There is potential for new technology to make people management training more flexible and interactive and to integrate with organisational support, guidance and advice.

- The Skilled Managers intervention is not a 'silver bullet' solution, and more holistic long-term approaches may be needed in certain contexts to embed and sustain change.

- Skilled Managers provides a possible blueprint for making high quality training and advice available to UK managers at scale and low cost.

7.1 Learning, development and delivery

Skilled Managers was developed as an online intervention as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic (see endnote 17), and this research study suggests that such low-burden approaches to training can have a significant impact. This may be of particular benefit in sectors (such as retail, hospitality, construction and social care) in which managers have limited access to the time needed for conventional longform training and development. Managers welcomed the flexibility, speed and accessibility of the course. Many participants commented on the level and nature of interaction, but very few indicated a preference for face-to-face contact, for instance:

It is important to note that the pilot version of Skilled Managers included group discussions via Microsoft Teams (Neves et al, 2023). This element was removed because engagement with these sessions was limited by constraints on managers' time. However, the need for this seems to have been counteracted somewhat by a virtual instructor who delivered most of the content and was the main 'contact' for individual managers. This seemed to give managers the sense of personal interaction they may otherwise have lacked:

'The way you framed the course around the main presenter talking directly to camera - and doing it well - made it feel like I was learning directly from him.'

(Manager, Social Care)

As discussed earlier, the research clearly points to the effectiveness of the intervention within smaller organisations. Budgetary restrictions and a lack of access to HR support meant that Skilled Managers was seen as a significant opportunity and implies a need that conventional long-form training is not meeting. Perhaps most importantly, Skilled Managers potentially enables all managers in an organisation to be trained in a time- and cost-efficient way. This makes it more likely that training can have a transformational approach on organisational cultures.

7.2 Closing the capability gap?

The evidence clearly suggests that Skilled Managers can play a role reducing managerial capability deficits in many UK workplaces. Perhaps most importantly, it provides an opportunity for high quality training to be provided by subject experts at scale and at relatively low cost. It also points to ways in which new technology can be used to enhance skills development - participants in the project found the use of short video content, interactive scenarios and simulated conversations particularly helpful. Moreover, using online delivery makes it easier for organisations to gather a range of data regarding engagement and impact of training. For example, it is possible to measure responses to questions and scenarios and track the amount of time spent on the course. This in turn can help to inform organisations' learning and development strategies.

In addition, the use of online learning platforms has the potential to integrate learning and development and systems of HR advice and guidance. In the Skilled Managers intervention, learners had the opportunity to link to their own organisational procedures and/or Acas advice and guidance while learning. They could also download templates and planning tools; they had the opportunity to message tutors in real time; and could arrange 1-2-1 video coaching sessions. This could easily be adapted to organisational systems so that managers had a one-stop-shop to access learning, policy, guidance, documentation and direct access to HR advice. This would be particularly powerful given the increasing centralisation and remoteness of many HR functions.

7.3 Challenges, limitations and barriers

The research highlighted the challenges of conducting robust evaluations within workplaces. Undoubtedly, the research would have been strengthened by conducting the evaluation over a longer period. However, maintaining engagement with organisations and participants is difficult, particularly when the method involves withholding potentially beneficial training from a group of managers. Moreover, maintaining a strict demarcation between treatment and control groups was problematic in some organisations.

Although the Skilled Managers intervention had a positive impact on most managers and organisations that took part in the research, this was context-specific. In larger organisations with more complex structures, it may be difficult to drive manager buy-in, placing a premium on senior leadership support. Good relationships between managers and HR will also create an environment in which managers view the offer of training positively. Therefore, where organisations have deep-rooted problems and where there is a lack of trust between line managers, HR and senior leadership, more extensive solutions may be needed to drive significant cultural and organisational change.

7.4 The wider policy agenda

There is a compelling case for building the conflict confidence and competence of managers. Improving these line management skills will not only minimise the cost of conflict but also help to make UK workplaces more productive. However, there are few signs that this skills gap is being filled and the huge interest in taking part in this study shows that there is an unfilled demand for training. In our initial outreach to participants of the main study, 1,000 places were booked for an introductory webinar in just under 3 hours, we had 291 expressions of interest in the project, with 150 of those being submitted within 2 hours of the webinar ending. Micro/small organisations made up 30% of applications.

The Skilled Managers research programme shows that low-burden training can be effective, delivered cheaply and at scale. It offers a possible blueprint for making high quality training and advice available to UK managers more widely – in such a way that extends reach, while allowing for the fact that some organisations will require more intensive and extensive interventions. Given the incidence, impact and cost of conflict in UK workplaces (Saundry and Urwin, 2021), this may have the potential to help save employers in aggregate billions of pounds annually.

8. Conclusions

The UK has a long-standing problem with managerial quality and capability. Arguably this is one of the root causes of persistently low levels of productivity which stifle economic growth and have become a key issue for successive governments. More specifically, Acas, CIPD, CMI and a range of other organisations have highlighted the problems caused by line managers who lack the confidence to resolve conflict and improve working relationships.

However, despite its importance there is little robust research on the effectiveness and impact of managerial training.

The Skilled Managers research programme was developed to answer a fundamental question: can training develop more 'conflict confident' managers who have a positive impact on their staff and organisations?

To answer this crucial question, the research first asked, what are the conflict management styles of managers and how are these shaped by key contextual and demographic factors?

The findings here were mixed. On average, more collaborative styles, which emphasise problem-solving, are dominant. However, there was also evidence of relatively high levels of avoidance, reinforcing two decades of research on this topic. Not surprisingly, there was a link between experience and conflict confidence. Crucially, organisational context and particularly organisational size was found to be important in shaping conflict management style.

Second, we measured the impact of the Skilled Managers intervention on conflict management style, which we argue reflects conflict confidence and competence. Across each dimension, average scores improved significantly, and most managers became less avoidant and more collaborative. These impacts were again linked to organisational effects, with reduced avoidance greatest in micro/small organisations.

The positive impact of the intervention was also reflected in feedback from managers, which we used to assess whether Skilled Managers fulfilled their training needs. Managers who completed the course were overwhelmingly positive about the design and approach of the course, citing the level of interactivity and use of video, scenarios and simulations.

In particular, much of the feedback focussed on flexibility, suggesting that this type of approach helps to deliver training to managers who might otherwise not have sufficient time, space or support for conventional training approaches.

The key test of the intervention is its impact on managerial practice and staff experience. Among managers in the micro/small-organisation sample, eight in ten felt that the training would change their practice and nearly 40% had already made alterations by the time they completed the course. These changes were felt by staff, with significant improvements in several key indicators.

In larger organisations, we were able to strengthen the analysis by having separate treatment and control groups of managers. There was evidence in most organisations that the intervention had a positive impact on the way that managers were addressing conflict in their teams, albeit with effectiveness shaped by organisational factors.

Overall, the research has significant implications for workplace practice and the role of Acas.

First, it demonstrates that low-burden interventions can help to build confidence and capability, particularly among managers who would otherwise miss out on training.

Second, the impact of training has a particularly strong impact in smaller organisations, which may help solve the UK's productivity puzzle.

Third, the approach used in the intervention offers a potential blueprint for organisations to develop smarter and more integrated systems for providing hard-pressed line managers with skills, support and guidance.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it suggests a cost-effective route through which government could support organisations to develop the conflict competence of their managers.

References

Bloom N and Van Reenen J (2007). 'Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries', Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (4), 1351–1408.

Bloom N, Eifert B, Mahajan A, McKenzie D and Roberts J (2013). 'Does management matter? Evidence from India', The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (1), 1–51.

Bloom N, Brynjolfsson E, L. Foster, R. Jarmin, M. Patnaik, I. Saporta-Eksten, and J. Van Reenen (2018). 'What drives differences in management practices?', Technical report, Working Paper, Stanford University.

Bowyer A, Kameshwara K, Latreille P, Saundry F, Saundry R and Urwin P (2024a). 'Gender Differences in Conflict Management Styles and Variation Across Workplace Settings' British Academy of Management.

Bowyer A, Kameshwara K, Latreille P, Saundry F, Saundry R, and Urwin P. (2024b). 'What shapes conflict management styles?', Labor and Employment Relations Association Conference.

Chartered management Institute (CMI) (2023). Taking Responsibility - Why UK PLC Needs Better Managers. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

CIPD (2020). Managing conflict in the modern workplace. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

Gosnell G K, List J A and Metcalfe R D (2020). 'The Impact of Management Practices on Employee Productivity: A Field Experiment with Airline Captains', Journal of Political Economy, Volume 128, Number 4.

Haldane (2020) in preamble to Carnegie UK Trust (2020). Can Good Work Solve the Productivity Puzzle? Collected essays, with RSA Future Work Centre.

Ichniowski C, Shaw K. and Prennushi G (1997). The effects of human resource management practices on productivity: A study of steel finishing lines. American Economic Review 87(2), pages 768–809.

Neves R, Latreille P, Saundry R, Urwin P and Maatwk F (2023). 'Engaging Managers with Online Learning in a Context of COVID Uncertainty: Challenges and Opportunities', in Avgar A, Lamare R, Hann D and Nash D (eds.) The Evolution of Workplace Dispute Resolution: International Perspectives, Labor & Employment Relations (LERA) Series, Cornell University Press.

Oliveira-Cunha J, Kozler J, Shah P, Thwaites G and Valero A (2021). Business time. How ready are UK firms for the decisive decade? The Resolution Foundation. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

Productivity Institute (2023). The Productivity Agenda.

Purcell, J (2014). Line Managers and Workplace Conflict, in WK Roche, P Teague, and A Colvin (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Conflict Management in Organizations, pages 405-424, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rahim M A (1983). 'A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict', Academy of Management journal, 26(2), pages 368-376.

Rahim M A (1983). 'Rahim Organizational Conflict Inventory–II', Journal of Applied Psychology.

Rahim M A (2002). 'Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict', International journal of conflict management, 13 (3); pages 206-235.

Sadun R, Bloom N and Van Reenan J (2017). 'Why Do We Undervalue Competent Management?', Harvard Business Review, September to October issue.

Saundry R, Fisher V and Kinsey S (2019). Managing workplace conflict: the changing role of HR, Acas Research Paper. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

Saundry R, Fisher V and Kinsey S (2022). Line management and the resolution of workplace conflict in the UK, in Townsend, K, Bos-Nehles, A and Jiang, K (eds.) Research Handbook on Line Managers, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pages 258-269.

Saundry R, Adam D, Ashman I, Forde C, Wibberley G and Wright S (2016). Managing individual conflict in the contemporary British workplace, Acas Research Paper. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

Saundry R and Urwin P (2021). Estimating the Costs of Workplace Conflict, Acas Research Paper. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

Saundry R, Latreille P, Dickens L, Irvine C, Teague P, Urwin P and Wibberley G (2015). Reframing Resolution: Managing Conflict and Resolving Individual Employment Disputes in the Contemporary Workplace, Acas Discussion Paper. Viewed on 8 August 2024.

Saundry R, Latreille P, Saundry F, Urwin P, Bowyer A, Mason S and Kameshwara K. (2024). Managing conflict at work – policy, procedure and informal resolution, Acas Research Paper (forthcoming).

Teague P and Roche W K (2012). 'Line managers and the management of workplace conflict: evidence from Ireland', Human Resource Management Journal, 22(3), pp.235-251.

Appendix

The ESRC study implements a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) in 24 UK-based organisations, randomly allocating managers in each organisation to distinct workplace units to receive the Skilled Managers online training ‘treatment’ and other units to a 'business as usual' control.

There are 362 units (for instance, 'departments' or 'branches') across the 24 organisations (containing 6,199 employees, not all of whom are 'in scope'), with the number of units within an organisation varying from 3 to 50.

Between October 2022 and April 2023, 510 managers were invited to complete the course as part of the treatment group (with a similar number in the control) and 410 managers registered on the training platform.

In addition to information on the activity of managers whilst on the training platform, we have before-and-after responses to a short Engagement (People) Survey from employee reports (1,801 respondents to the first, and 1,503 respondents to the second engagement survey, administered before their managers were trained and then at a point six months later).

10 question Engagement Survey

- On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being most likely, how likely is it that you would recommend this company to a friend or family member?

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "I think that my organisation respects individual differences (e.g. cultures, working styles, backgrounds etc)"

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "It’s easy for me to get feedback on my performance".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "Good performance in my team is recognised".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "Poor performance in my team is tackled effectively".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "I often experience work-related stress that impacts my health and job performance".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "If there is conflict in the team, my line manager helps resolve this quickly".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "Talking to my line manager helps me improve my performance".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "I have a good relationship with my line manager".

- To what extent do you agree with the statement, "I am happy in my role and am not thinking of leaving".

[Questions 2-9 use a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree]

As part of the Skilled Managers training, managers complete a questionnaire that utilises Rahim’s framework to operationalise conflict competencies into 5 management styles (Rahim, 1983; 2002). The questionnaire is used to provide an indication of the extent to which managers are (on average) 'integrating/problem solving'; 'obliging'; 'dominating'; 'avoiding’ or 'compromising' when faced with people challenges. The managers complete the questionnaire before and after training, allowing us to observe how the approach of managers changes as they gain additional insight.

In addition to the results presented from the Cluster RCT evaluation of the Skilled Managers intervention, the discussion draws to a limited extent on findings from an accompanying study that focused on organisations with fewer than 20 employees. This was an event study (i.e. without a control group) involving 38 organisations, with 747 employees and 235 managers. The average number of employees per organisation is 20, managed on average by 6 managers. All managers undertook the Skilled Managers training and we have the same engagement survey responses from staff before and after training impacts – these findings provide an additional check on key results that arise from the main cluster RCT study.

Endnotes

Endnote 1. We also touch on findings from Saundry et al, (2024), which considers Managing conflict at work – policy, procedure and informal resolution. Back to introduction

Endnote 2. Construction, Hospitality, Retail, Social Care, Industrial/Manufacturing, Building contractors, Education, Healthcare and Insurance. Back to introduction

Endnote 3. Managers in the control group were then given access to the intervention, as part of a second wave of the study. Back to introduction

Endnote 4. The study implemented a cluster RCT between October 2022 and April 2023 with managers of distinct workplace units within each organisation randomly allocated to either receive the Skilled Managers online training 'treatment' or a 'business as usual' control. The number of units within an organisation varied from 3 to 50 and not all 6,199 employees were in scope. Read the October 2022 protocol, which provides full technical details of the evaluation. Back to introduction

Endnote 5. The Main sample includes managers from both wave 1 and wave 2 of the Main (ESRC) Study. Back to 3.2

Endnote 6. We estimate an OLS regression to model conflict management styles, with gender, years of experience and ethnicity of managers, as well as organisational size as explanatory variables; across a combined sample of managers from the main ESRC-funded study and micro/small business study. Back to 3.2

Endnote 7. One of the specifications for our regression has fixed effects for each organisation and these are found to be significant in many cases. We combine the findings from this analysis with other aspects of our study to discuss the nature of these organisational effects later in the report. Back to 3.2

Endnote 8. For a more detailed discussion see Bowyer et al, (2024b). Back to 4.1

Endnote 9. These findings remain when we consider only the 572 managers who completed the inventory both before and after training. Back to 4.1

Endnote 10. These findings remain when we consider only the 152 managers who completed the inventory both before and after training. Back to 4.1

Endnote 11. For instance, whilst male and female managers both reduce – to a similar extent – their use of competing approaches as a result of training; we find the use of 'accommodating' styles is initially very similar on average, but the impact of the training is much more pronounced for female managers who see a reduction in this approach. Back to 5.2

Endnote 12. The figure of 84% is constructed from an initial review of the 621 qualitative feedback responses by a researcher, in advance of analysis using qualitative data analysis software. Back to 5.3

Endnote 13. For detail of the experimental design, including discussion of the Business-as-Usual approach to managers in the control, see the protocol. Back to 6.1

Endnote 14. The cluster RCT method dictates stringent approaches, for instance achieving certain levels of statistical power only by using specific approaches to statistical testing and a focus on only one primary outcome indicator. The discussion of findings in this summary report is more wide-ranging and we would encourage readers who wish to understand more of the technical detail of our data collection and analysis to refer to the protocol and accompanying academic papers. Back to 6.2

Endnote 15. It is important to note that whilst we do identify significant impacts in the micro/small business study relating to 'performance' across key indicators in our engagement survey, this is not the case in the main experimental study (where we observe no statistically significant impact of the Skilled Managers training on questions 3, 4, 5 or 8). More generally, whatever the size of organisation we found that key people management measures and performance indicators were not systematically collected in a way that could gauge further impacts on performance outcomes. This is a limitation of the study that continues to raise challenges for all researchers. Back to 6.2

Endnote 16. These findings are identified at the level of individual staff respondent, but we again refer readers to Bowyer et al, (2024b) for consideration of technical detail. Back to 6.2

Endnote 17. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic the initial intervention was conceived as a face to face one day training course delivered by Acas staff. Back to 7.1