Disclaimer

This is an independent research paper produced by Dr Joanna Yarker, Alice Sinclair, Dr Emma Donaldson-Feilder and Dr Rachel Lewis of Affinity Health at Work, a workplace health and wellbeing consultancy and research group.

The views in this research paper are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the author alone. This paper is not intended as guidance from Acas about how to make work adjustments for mental health conditions.

Executive summary

This review examines the evidence and guidance available to inform practices around work adjustments for mental health at work.

It is important that employees experiencing mental ill-health are able to access the support they need to return to work following sickness absence, stay in work and continue to work productively and safely. One way that employers can support employees with mental ill-health is through access to, and support for, work adjustments. However, little is known about which adjustments are effective, for whom and in what circumstances. Acas therefore commissioned Affinity Health at Work to conduct an evidence review with the aim of addressing this gap.

This review aimed to answer 3 key questions:

- What is going on in practice?

- What does the guidance recommend?

- What is the evidence?

Mental ill-health and work adjustments

In this report we consider all evidence relating to the broad spectrum of mental ill-health within the context of returning to and staying in work. The lack of clarity and specificity of mental health conditions reported in the literature reviewed means we are unable to provide a more granular analysis of the adjustments used in relation to different mental health conditions.

The terms work adjustments, workplace adjustments, reasonable adjustments, reasonable accommodations, work accommodations, task or job modifications and workplace intervention are used interchangeably within the literature and guidance. In this review we refer to the term work adjustments as defined as ‘a change or adjustment unique to a person’s needs that will enable them to do their job’ (Department of Health, 2019). However, we included all terms within our searches of the evidence.

Our approach

A rapid evidence assessment was used to provide a review of what is known (and not known) in the academic and practitioner literature about work adjustments for mental ill-health. 21 peer reviewed studies and 8 practitioner reports that met our search and inclusion criteria were identified using a rapid evidence assessment (Barends, Rousseau & Briner, 2017). We evaluated the strength of the available research using the Nesta Standards of Evidence (Puttick & Ludlow, 2013). 19 guidance materials providing recommendations on adjustments for mental health were identified and evaluated using the AGREE framework (Brouwers, 2013).

Findings

What is going on in practice?

Access to, and the implementation of, work adjustments for employees with mental ill-health appears to be varied and inconsistent. The most commonly applied work adjustments included flexible scheduling/reduced hours, modified training and supervision, and modified job duties/descriptions. However, findings suggest that employees struggle to access work adjustments and managers are ill-equipped to support employees in their endeavours to access them (BITC, 2019). Reports including the Stevenson/Farmer review encourage employers to prioritise work adjustments for employees with mental ill-health. However, a clear picture of the current practices in the UK is lacking.

What does the guidance recommend?

19 different pieces of guidance on work adjustments for mental health were identified from our search of UK stakeholder organisations including Acas, Chartered Institute of Personnel Development, Health and Safety Executive, Mind and government resources among others. The guides are largely accessible and engaging. While there is some consistency in the recommendations regarding what work adjustments may be appropriate, there is little consistency in the terms used or clarity in the pathways to access work adjustments. There is limited consideration of when to implement work adjustments or how to implement them and only 2 of the guides were specifically designed for employees. When considered using the AGREE framework, guidance is limited by the absence of a robust evidence based to guide practice.

What is the evidence?

Five overarching themes were identified in this evidence review:

- Work adjustments are perceived to be effective by employees, colleagues, managers, employers and stakeholders (for example human resource professionals, occupational health).

- There are a number of different pathways to access work adjustments reported in the research including case workers, line managers, human resource professionals, general practitioners and occupational health professionals.

- There are a number of barriers and facilitators to accessing and implementing work adjustments successfully. Implementing multicomponent interventions, encouraging disclosure and facilitating supervisor and co-worker support are likely to enhance the likelihood of the work adjustment being reported as successful.

- The evidence for effectiveness is less clear. Only a small number of studies show an association between work adjustments and health outcomes. Few studies follow employees over time to assess the longer term impact of work adjustments. Of these longitudinal studies that do exist, graduated returns demonstrated mixed findings and no evidence was found on the effectiveness of specific workplace adjustments, such as flexible working or workload modifications in any of the 7 systematic reviews included in this review. No controlled studies were identified in this review that examine the use of specific work adjustments (where individuals who are afforded specific adjustments are compared to those who are not). A mapping of available research against the Nesta Standards of Evidence shows that evidence in the area of work adjustments for mental health is in its infancy.

- We found no evidence that different adjustments are recommended to individuals in relation to:

the severity of their mental ill-health; their job role; the sector in which they work or whether their mental ill-health falls under the Equality Act or outside it.

There is little published research to inform our understanding of what work adjustments employees working in the UK access, how they access them and to what effect. While anecdotal evidence suggests that work adjustments are used, there is a need to better understand and share more widely how employers are measuring the impact of work adjustments, how employees access them and how those working alongside employees with adjustments respond. Our understanding of the effectiveness is also limited by the absence of robust longitudinal studies. The lack of granularity and specificity in the measurement of both mental health and work adjustments within the research means we cannot tell which adjustments are most useful, for whom, under what circumstances. However, it is important to note that the lack of evidence does not mean they do not work, it just means we do not have evidence that they work.

Summary and recommendations

To ensure that employees are able to access work adjustments, and that where these are accessed they are of benefit to both the employee and organisation, there is need to: to develop a clear picture of current practices in the UK; enhance the guidance available to employees, colleagues, managers and professionals working within occupational health and human resources; and build the evidence base for work adjustments for mental ill health. Specific actions to drive forward the research and enhance guidance are recommended. Taking these steps will help ensure that employees with mental ill-health are offered clear and consistent advice, in a way that is timely, supportive and enables them to better manage their mental health and maintain their ability to work.

1. Background and aims of the review

This review examines the evidence and guidance available to inform practices around work adjustments for mental health at work.

One in 6 employees in the UK report mental ill-health, such as anxiety or depression, each week (McManus and others, 2016) and a third of fit notes with a known diagnosis note mental or behavioural disorders as the reason for absence (NHS Digital, 2017). As such, mental ill-health is a growing concern for employers. It is important that employees experiencing mental ill-health are able to access the support they need to return to work following sickness absence, stay in work and continue to work productively and safely. One way that employers can support employees with mental ill-health is through access to, and support for, work adjustments.

1.1 Defining mental ill-health

The term ‘mental ill-health’ is a broad umbrella term that includes a range of experiences: from every-day worries and feeling down, to common conditions such as anxiety and depression, to less common or more serious long-term conditions such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. The terms mental illness or mental health condition or common mental disorder are typically used for medically or clinically diagnosed conditions that impact on cognitive, emotional or behavioural functioning. The term mental health problems typically refer to less enduring experience that occur due to stressors experienced by the individual that impact on cognitive, emotional or behavioural functioning. Some people may experience a one-off period of mental ill-health while for others their mental ill-health may be more long-term and fluctuating in nature. It is important to note however that individuals experiencing mental ill-health differ in the extent to which they are able to manage their mental ill-health at work.

Within the literature reviewed in this report, the classification and diagnosis of the employee is often unclear and the terms mental ill-health, mental health problems or mental health conditions are used interchangeably. No studies compared the work adjustments used by employees with different mental health conditions. Therefore, in this report we consider all evidence relating to mental ill-health within the context of returning to and staying in work but are unable to provide a more granular analysis of the adjustments used in relation to different mental health conditions.

1.2 Defining work adjustments

The terms work adjustments, workplace adjustments, reasonable adjustments, reasonable accommodations, work accommodations, task or job modifications and workplace intervention are used interchangeably within the literature and guidance. The term ‘work accommodation’ is most frequently used across peer reviewed papers, research reports and guidance materials.

In this review we refer to the term work adjustments but included all terms within our searches of the evidence.

Expanding on this definition, work adjustments are typically temporary and require ongoing monitoring, are agreed between the manager and employee, and may or may not include stakeholder involvement (for example from Human Resources, Occupational Health or other specialists). Reasonable adjustments are more likely to be longer-term and are more likely to include stakeholder involvement.

There is no agreed classification of work adjustments. However, adjustments are most often made in one or more of the following areas:

- work schedule for example flexible hours, increased breaks, leave for appointments

- role and responsibilities for example reduced workload, temporary change in duties

- work environment for example home working, relocation of desk

- additional support and assistance for example buddy or mentor, additional training on skills and duties

- redeployment

- policy changes for example adjustment to the absence management policy to accommodate fluctuating condition

A mapping of evidence and recommendations made in the guidance against specific work adjustments is provided in Appendix 6.

1.3 Why is it important for us to understand the evidence for work adjustments for mental health?

Mental ill-health is now the most prevalent reason for short- and long-term sickness absence (HSE, 2019). Many employees find it difficult to maintain work on their return from sickness absence. Some figures suggest that 20% of returners subsequently relapse (Norder and others, 2017) and approximately 300,000 people leave work every year with a mental health condition (Stevenson/Farmer, 2017). One way to support employees with mental ill-health return to and stay at work, aside from clinical or therapeutic intervention, is to offer work adjustments or accommodations. However, little is known about which adjustments are effective, for whom and in what circumstances. Acas therefore commissioned Affinity Health at Work to conduct an evidence review with the aim of addressing this gap.

This review aimed to answer 3 key questions:

- What is going on in practice?

- What does the guidance recommend?

- What is the evidence?

2. Our approach

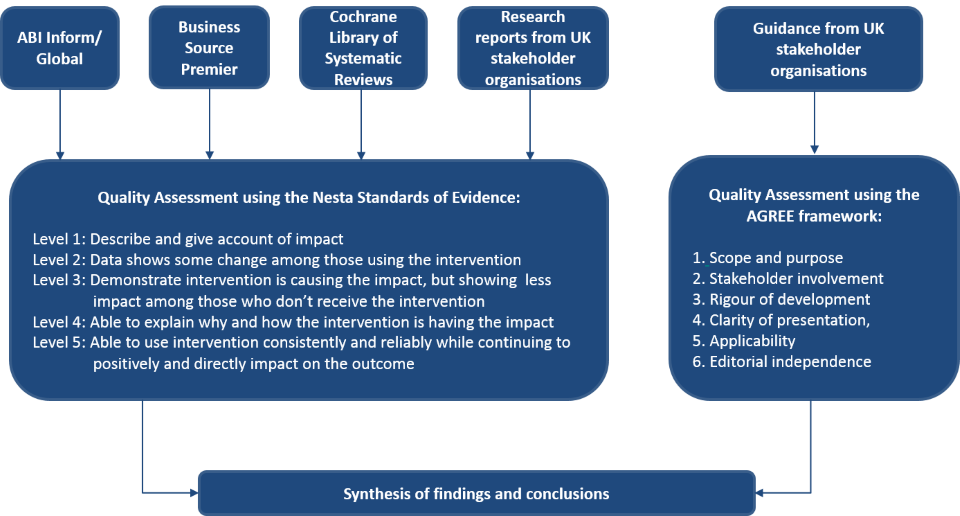

A rapid evidence assessment was used to provide a review of what is known (and not known) in the academic and practitioner literature about reasonable adjustments for mental ill-health. Using the systematic approach as outlined by Barends, Rousseau & Briner (2017), the research team searched, identified and critically evaluated the strength of the evidence. Further details of the methodology, including the search terms used and hits elicited, are included in the Appendices 1 and 2 and the approach is summarised in Figure 1.

2.1 Identifying terms, databases and relevant sources of information

The search terms, databases and relevant stakeholder organisations were decided upon by conducting a scoping phase to understand the breadth of the literature and the terminology used. These findings were used as a platform for discussion by the research team to identify search terms specific to wellbeing and mental ill-health, work or workplace and interventions (for example adjustments, accommodations).

This rapid review of the evidence and guidance considers the following sources:

- peer-reviewed, scholarly articles written in English; the searches were conducted in ABI Inform, Business Source Premier and the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews

- research reports from UK stakeholder organisations

- guidance material from UK stakeholder organisations

2.2 Selecting the studies for inclusion

The studies were selected for inclusion using a 3-stage process. First, a title sift was conducted. Titles were retained if they focused on work adjustments and mental health. Second, an abstract sift was conducted where abstracts were retained if they were written in English, conducted in a work setting and contained empirical data were included. Where detail was insufficient in the abstract, full papers were reviewed. Finally, full papers were reviewed and retained if they met the inclusion criteria.

2.3 Critically evaluating the studies and guidance

The strength of the available research was evaluated using the Nesta Standards of Evidence (Puttick & Ludlow, 2013). While there are many standards of evidence available, the Nesta framework was chosen as it retains academic rigour while informing practical deliverables. The 5 levels of evidence span Level 1 (able to describe the impact) to Level 5 (able to consistently replicate findings impacting the outcome, using randomised designs to enable causal inferences, across situations). This framework provides a useful steer as to the maturity of the evidence available in an area and can direct future research. It is typical for new and emerging areas of interest to have a small number of descriptive studies. Where the evidence base and practice in an area is well established, a number of studies with robust randomised designs would be expected.

The available guidance was evaluated using the AGREE framework (Brouwers, 2013). The AGREE framework is a widely used standard for assessing the quality of practice guidelines in healthcare. The framework provides a series of statements across 6 areas relating to the design and content of guidance against which any guidelines can be evaluated. The framework was developed to improve the transparency, engagement and standardised implementation of guidelines in healthcare and in doing so, improve treatment and health outcomes. The framework has more recently been applied in community and workplace settings and, while not all components are practicable in all workplace settings, it offers a useful starting point from which to identify future developments to improve workplace guidance.

An overview of the Nesta Standards of Evidence and the AGREE Framework are shown in Figure 1 and described fully in Appendix 3 and 5.

A rapid evidence assessment enables a systematic and transparent approach to the searches and quality assurance processes employed. However, it is important to note that this approach is somewhat constrained when compared to a full systematic literature review and meta-analysis. A broader database search, inclusion of unpublished studies or the application of more stringent quality appraisal criteria may have yielded some additional findings to those presented in the sections that follow.

Based on the studies that emerged from this process, the following sections summarise the evidence (what was found?) and synthesise the findings (what does it mean?) in order to draw conclusions, identify the limitations of the current evidence base, and draw out the implications for research and practice. The findings were then shared with a group of practitioners from UK public and private sector organisations and stakeholder representatives from the HSE, Acas and IOSH to check sense-making. The findings were believed to be representative of the experience of practice by this multi-disciplinary group.

3. The findings

3.1 What is going on in practice?

Access to, and the implementation of, work adjustments for employees with mental ill-health appears to be varied and inconsistent. Reports drawing on national surveys conducted with human resource professionals, business owners and employees working across a range of sectors, regions and business size provide a broad indication of current practices in relation to work adjustments for mental ill-health. These findings suggest the following.

There are a number of different stakeholders involved in supporting employees to access work adjustments: human resource professionals, occupational health professionals, general practitioners, mental health practitioners and line managers are all recognised as playing a role in helping employees put work adjustments in place. However, there is no clear or consistent pathway through which employees access work adjustments nor is there any clarity around when and why different professionals are involved in the process.

Phased returns or other work adjustments are the practice most widely used to manage employee mental health at work: In a survey of 1,078 organisations, 61% of organisations reported that a phased or gradual return and/or other reasonable adjustments was the most common action taken in relation to mental health (CIPD, 2019). In a systematic review within which mental health was one of the conditions included (among other health conditions), the most commonly applied work adjustments included: flexible scheduling/reduced hours, modified training and supervision, and modified job duties/descriptions (A1). These adjustments are echoed throughout the evidence and guidance reviewed (see Table 2 for a summary of adjustments reported). However, there is no detailed breakdown of the specific adjustments recommended or used by employees with mental ill-health available in academic or practitioner literature.

Too few employees access the work adjustments that they need: In a survey of 4,236 employees, 41% of employees experiencing a mental health problem reported that no actions had been taken at work (BITC, 2019).

Managers are ill-equipped to help employees put in place work adjustments: 8% of managers reported that they had received training on adjustments and rehabilitation, while 70% of managers reported that there are barriers to them providing support for employees with mental ill-health (BITC, 2019).

We do not have a clear picture of current practices: There was no specific information available relating to: the number of people with mental ill-health currently working with the benefit of adjustments; what specific adjustments are being implemented; how adjustments are accessed and implemented; or how adjustments are monitored and reviewed in practice. Given the number of employees reporting that they experience mental ill-health, there is need for a clearer and more granular picture of what is going on in practice.

However, there have been a number of positive steps to encourage organisations to prioritise the provision of work adjustments for employees with mental ill-health. Notably, the recommendations made in the Stevenson/Farmer review and the BITC Mental Health at Work 2019 report.

Work adjustments are recognised within the Mental Health Core Standards for Employers in the Stevenson/Farmer review (2017). This focuses employers’ attention on the need to provide access to work adjustments for employees when required.

Core standard 3 states: "Encourage open conversations about mental health and the support available when employees are struggling, during the recruitment process and at regular intervals throughout employment, offer appropriate workplace adjustments to employees who require them."

Management training for work adjustments and modifications is recommended in the Mental Health at Work 2019 BITC report as a key action underpinning the provision of tailored support for employees with mental ill-health. The recommendations made in this report are supported by the BITC’s 9 national partners.

Summary of current practice:

Much activity is going on, but practices vary and are inconsistent. There is no clear information about what adjustments are being used, by whom, or how employees access them.

3.2 What does the guidance recommend?

19 different pieces of guidance on work adjustments for mental health were identified from our search of UK stakeholder organisations including Acas, Chartered Institute of Personnel Development, Health and Safety Executive, Mind and government resources among others. To allow for cross-referencing of guidance, we have given each guidance material a code G1-G19 outlined in Table 1. The full details and link to the guidance material can be found in the references section.

Table 1: Guidance reference number, author and guidance title

| Reference number | Author and guidance title |

|---|---|

| G1 | Acas - Common adjustments for staff experiencing mental ill health |

| G2 | Access to work - fact sheet for employers |

| G3 | BITC - Mental health toolkit for managers |

| G4 | BITC - Mental health toolkit for organisations |

| G5 | BUPA - Supporting employees with mental health problems |

| G6 | CIPD MIND - Managing and supporting mental health at work disclosure tools for managers |

| G7 | CIPD MIND - People managers guide to mental health |

| G8 | DOH - Advice for employers on workplace adjustments for mental health conditions |

| G9 | DWP - Employing disabled people and people with health conditions |

| G10 | Heads Together - Mentally Healthy Schools |

| G11 | HSE - Managing sickness absence guide for managers and employees |

| G12 | IAPT NHS Berkshire - Self-help booklet return to work |

| G13 | MHF UNUM - Managing mental health in the workplace |

| G14 | MHFA - Line manager resource |

| G15 | Mind - How to support staff who are experiencing a mental health problem |

| G16 | Mindful employer - Making work work |

| G17 | Rethink Mental Illness - What’s reasonable at work |

| G18 | Scottish Association for Mental Health - Reasonable adjustment booklet |

| G19 | SHIFT DOH HSE DWP - Line managers guide to mental health |

A review of the contents of the guides found that:

- 6 were specifically focused on adjustments (G1, G2, G8, G9, G17, G18), while 13 were more generally focused on the management of mental health at work (of which work adjustments was one aspect)

- 7 referred to the broad spectrum of mental health and the implications of severity for adjustments (G2, G6, G7, G13, G14) but did not specify different adjustments for the different conditions

- 4 were specifically designed to support return to work following absence, while 14 included ‘at work’ adjustments or did not specify when the adjustments could be put in place

- all but one referred to the Equality Act (G1), although materials associated with this guidance made reference to the Equality Act

- 2 pieces of guidance were employee focused, 9 were designed for employers, 5 for managers, 2 for employees and employers and one was unspecified

A number of work adjustments were recommended in the guidance. The most frequently recommended adjustments are summarised in Table 2. A full mapping of the guidance can be found in Appendix 6.

Table 2: Work adjustments recommended in the guidance

| Type of adjustment |

Recommended in the guidance? (Number of guides that recommend this adjustment) |

|---|---|

| Work schedule | Breaks (4), Leave for appointments (8), Flexible hours (9) |

| Role and responsibilities | Review workload (3), Temporary change in duties (5) |

| Work environment | Home working (7), Relocation of desk (6), Light box (2) |

| Policy changes |

Extended leave for appointment (1), Changes to absence management policy (1) |

| Additional support and assistance |

Buddy or mentor (5), Modified supervision (3), Additional training on skills and duties (7) |

| Redeployment | 3 |

Please note: frequencies are not cumulative as different guidance materials recommend different adjustments.

Consideration of the guidance against the AGREE framework indicates that the available guidance is largely accessible and engaging. Stakeholder involvement was noted in a number of the guides (for example G3, G4, G19) but the information available suggested that none were editorially independent. However, as the evidence base for work adjustments is in its infancy, guidance may be well-intentioned but is largely unevaluated and unsubstantiated. This may in part explain why so many people struggle to access and implement work adjustments, and subsequently experience difficulties in managing their mental health and maintaining work.

Summary of the guidance

There is some consistency in the recommendations regarding what work adjustments may be appropriate, but little consistency in the terms used. There is limited consideration of when to implement work adjustments or how to implement them. There are notably few resources for employees, and therefore employees are likely to be ill-equipped to ask for work adjustments.

3.3 What is the evidence?

This review of evidence included:

- 7 systematic reviews

- 3 longitudinal studies, one of which was a controlled trial comparison

- 6 cross-sectional survey studies

- 5 qualitative studies and 8 practitioner reports

To allow for cross-referencing of the evidence reviewed, we have given each source a code A1-21 for academic peer reviewed journal articles and R1-8 for research reports. The codes are presented in the reference section. A synthesis of the evidence is presented here and a summary of the study design, findings and implications are outlined in full in Appendix 6.

Five overarching themes were identified in this evidence review.

1. Work adjustments are perceived to be effective by employees, colleagues, managers, employers and stakeholders (for example human resource professionals, occupational health). A number of studies that gathered self-report data from employees, either through interviews or questionnaires taken at a single time point, show that employees describe a range of work adjustments as being helpful. These studies provide descriptions of the work adjustments used and logically and coherently describe how and why these adjustments are of benefit. These findings show that:

- employees perceive the work adjustments to be effective. (A11, A12, A13, A15, A16, A20, R3, R6). One study found that employees with anxiety disorder reported that work adjustments enabled them to perform well at work as they allowed them to keep stress at a manageable level (A16)

- co-workers recognise the benefits of work adjustments for their colleagues experiencing mental ill-health (A14); interestingly, co-workers see the work adjustments of flexible hours and time off for counselling as more acceptable than more frequent breaks, possibly due to the perceived fairness and impact on the team during the working day

- managers recognise the benefits of work adjustments and are prepared to take action (A18, A20, A21); adjustments such as providing assistance, feedback, recognition and support were noted (A18), however, many managers recognise the need for further support and experience difficulties in realising and implementing work adjustments (R5), and would like recognition of the constraints that they are working within (A21)

- employers and human resource professionals recognise the benefits of work adjustments (A17, A19, R2, R6). They note the importance of continual responsiveness and the importance of disclosure in putting in place effective adjustments

- employees focus on different aspects than employers and human resource professionals; human resource professionals and employers focus on work aspects (for example job modifications); telephone interviews with 219 human resource directors and employers found that the interviewees readily discussed the specific changes that could be made to the work environment and job, but the relational aspects and involvement of different stakeholders (for example, line managers) are not prioritised (for example A17); in contrast, employees focus on the relational aspects (such as the need for support, good relationships) and fair treatment (A15, A20)

2. There are a number of different pathways to access work adjustments reported in the research. These include case workers (A4), line managers (A3), occupational health (A10) and general practitioners (R5). The co-ordination between pathways is the focus of one study (R5). In this study, there was a common pathway in that the return to work was managed by the occupational health physician as is required by law in the Dutch social security system. No study examined the frequency with which different pathways are used or enforced, whether they supported decisions or provided support, or the effectiveness of these different pathways.

3. There are a number of barriers and facilitators to accessing and implementing work adjustments successfully.

Multicomponent interventions appear to be more successful (for example work adjustments plus health focused CBT plus service co-ordination) to single-component interventions (A2), and were perceived by patients to offer the best improvement in terms of work ability (A10).

Encouraging disclosure is important – those who disclose are more likely to access adjustments but stigma remains a concern and disclosure does not necessarily mean that adjustments will be made. 39% saw no adjustment made (R3). Findings suggest that the lack of awareness of rights, combined with stigma of mental health, leads people not to disclose (A3, R5) which is a concern as without disclosure, appropriate adjustments cannot be identified. No information was available regarding differences in disclosure related to the type or severity of mental ill-health.

Supervisor support is important – those who report support also report feeling safe and able to access adjustments. Managerial decision makers who remain open-minded (A15) and supportive (A13) of accommodations are needed to ensure the accommodations are put in place successfully.

Co-worker support is important – specifically in relation to helping employees feel safe and able to access work adjustments (R4 - R7).

Job coaches were available to employees in one study and employees reported that the support enabled them to have more effective communication with managers and therefore better access to accommodations (A3). While not a common practice, the role of a third party outside the manager-employee relationship has been found to be useful in mediation communications.

There is a shared understanding between stakeholders of the barriers and facilitators to accessing work adjustments, but stakeholders hold different perspective about why these occur. In one study (R5) mental health professionals, occupational health professionals and GPs reported common barriers including returning to an unsympathetic work environment with limited or difficult to implement work accommodations, while GPs noted that often nothing has changed in the work context. In contrast, managers reported the lack of opportunities to realise changes at work due to limited means or space for creative solutions. Interview studies report shared experiences from the different groups including Human Resource directors (A17), supervisors (A18) and employers responsible for hiring (A19). In these studies, respondents were generally supportive and open to a range of accommodations yet employees perceived their need for accommodations was more extensive than employers recognised (A20) and managers were keen for the difficulties in implementing accommodations to be more fully recognised (A21).

4. The evidence for effectiveness is less clear. While a small number of studies show an association between work adjustments and health outcomes, there are few studies that follow employees over time. However, the findings are mixed.

There is some evidence to indicate that work adjustments are associated with work and health outcomes. Studies A1, A3, A8, A10 and R5 examined the relationship between work adjustments and work and health over time. Of these, only A10 reported significant findings. In this study, it was found that work adjustments in combination with clinical treatment were effective.

Longitudinal analysis of graduated returns demonstrated mixed findings. A study using Dutch administrative data found no impact (A8), while a controlled trial suggested there may be benefits for those with long-term mental ill-health issues (A9). However, individuals in the latter study had also undergone an intensive external rehabilitation programme and therefore the causality of the graduated return cannot be inferred.

No evidence was found on the effectiveness of specific work adjustments, such as flexible working or workload modifications in any of the 7 systematic reviews (A1-A7) and no controlled studies examining the use of specific work adjustments (where individuals who are afforded specific adjustments are compared to those who are not) were identified in this review.

A mapping of evidence against the most frequently recommended work adjustments is provided in Table 3. This shows that there is some research that describes the effectiveness of work adjustments, and some that demonstrates an association between work adjustments and work and health outcomes, but no research demonstrating a causal link. Interestingly, policy changes and redeployment have received little research attention.

A mapping of evidence against the Nesta Standards of Evidence is provided in Table 4. This shows that evidence in the area of work adjustments for mental health is an emerging area of research. There are a number of studies that logically describe the effect of work adjustments and a few studies that demonstrate that work adjustments are associated with work and health outcomes. Further research is required to demonstrate that work adjustments are the reason for any improved work or health outcomes reported by employees with mental ill-health.

Table 3: Evidence mapped against frequently recommended work adjustments

| Type of adjustment | Evidence in research reports | Evidence in peer reviewed journals |

|---|---|---|

| Work schedule | described | association reported |

| Role and responsibilities | described | described |

| Work environment | described | described |

| Policy changes | ||

| Additional support and assistance | association reported | association reported |

| Redeployment | described |

5. We found no evidence for differences in work adjustments recommended or accessed.

In relation to the severity of mental ill-health for example for transitory ‘every day’ anxiety to severe mental ill health. The research is hampered by the lack of clarity of concepts used (for example burnout, stress, mental health, depression) and the absence of information regarding whether the research participants have a clinically diagnosed condition (for example A1). Some evidence to suggest that work-directed interventions in addition to clinical interventions are more effective than clinical interventions alone for those with high levels of depressive symptoms (A6) in achieving return to work; while one study demonstrated that work adjustments were beneficial for those presenting with severe mental ill-health, yet also concluded that those participants had also received intensive support and therefore are not likely to be representative of employees with mental ill-health typically accessing work adjustments (A9).

While at work or at the point of return. Our search terms aimed to capture information about adjustments made both while an employee is in work (that is, preventative prior to absence) and on return to work. We did not identify any research that specifically related to adjustments made while the employee was in work, to prevent deterioration for example, but rather all studies examined adjustments following a period of absence.

Where an employees’ mental ill-health falls under the Equality Act and those that fall outside. We did not find any studies that specifically examined this, nor are the work adjustments suitable for employees protected by the Equality Act differentiated within the guidance. Rather, when the Equality Act is referred to within guidance material, the term ‘reasonable adjustments’ rather than 'work adjustments' is used. Interestingly, an interview study with employee and manager pairs reported than none of the managers interviewees mentioned their legal obligation to provide work adjustments but rather supported adjustments as the right thing to do (A20).

In relation to sector or job roles. The majority of the research drew from broad participant samples and no comparisons between sector or job roles were reported in the studies reviewed.

Through the involvement of occupational health professionals, human resource professionals or supervisors that is, different disciplines seem to be recommending the same work adjustments and acknowledging the same barriers and facilitators (R4).

While survey and interview studies suggest a range of adjustments are useful, longitudinal studies show mixed findings. There is no evidence for the effectiveness of specific work adjustments as measured by longitudinal, controlled studies. The lack of evidence does not mean they do not work, it just means we do not have evidence that they work.

Table 4: Evidence mapped onto the Nesta Standards of Evidence

| Nesta Standard of Evidence | Nesta expectation | What this means in relation to work adjustments | Studies within the review with designs at this level | Studies with significant findings within this review at this level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | You can describe what you do and why it matters, logically, coherently and convincingly | Descriptions of work adjustments, and reported benefits of why and how they make a difference for example qualitative data or cross-sectional survey | A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16, A17, A18, A19, A20, A21, R1-R8 | A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16, A17, A18, A19, A20, A21, R1-R8 |

| Level 2 | You can capture data that shows a positive change, but you cannot confirm you caused this | Work adjustments are associated with work and health outcomes for example over-time survey data | A1, A3, A8, A10, R4 | A10, R4 |

| Level 3 | You can demonstrate causality using a control or comparison group | Specific work adjustments offer benefits over those afforded to a control group for example Controlled trial, over time, using quantitative measures | A2, A4, A5, A6, A7, A9 | A9 (for severe mental ill-health only) |

| Level 4 | You have one + independent replication evaluation/s that confirms these conclusions | Replication of controlled trial, preferably a randomly controlled trial comparing specific work adjustments | None | None |

| Level 5 | You have manuals, systems and procedures to ensure consistent replication and positive impact | Specified pathways to access specific work adjustments, delivered in a systematic and replicable way | None | None |

3.4 Limitations of the research identified in the rapid evidence review

There is a limited understanding of work adjustments in a UK context. The majority of the available peer-reviewed research has been conducted in the Netherlands, Australia, Canada, US and Sweden. Employees in each country navigate access to adjustments in different external contexts in relation to employment practices, social security benefit and health care provision. For example, in Sweden, social insurance officers are involved in return to work, while in the Netherlands the employer is responsible for the employee’s sick-pay for the first 2 years of absence. There is a need to understand the access to, implementation of, and the effectiveness of work adjustments in the context of the health and social care provisions available to employees in the UK.

There is a lack of granularity and specificity in relation to mental health in the research. A broad range of mental health concepts (for example stress, burnout, clinically diagnosed condition) are used and researchers do not define the specific parameters of mental health that they are measuring (A1, A7).

There is a lack of granularity and specificity in relation to work adjustments in the research. The specific work adjustments used by employees are ill described (for example A1, A3, A7).

Research in the area of work adjustments for mental health is largely in its exploratory phase as identified in Table 4. Studies identified in this review are largely descriptive (for example 11-21), while many of those that followed employees over time did not allow for the isolation of specific adjustments (for example home working) to enable the evaluation of effectiveness (for example A1-10).

Summary of the limitations of the research

There is little understanding of what work adjustments employees working in the UK access, how they access them and to what effect. The lack of granularity and specificity in the measurement of both mental health and work adjustments within the research means we cannot tell which adjustments are most useful, for whom, under what circumstances. The absence of robust longitudinal studies hamper our understanding of the effectiveness of work adjustments.

4. Summary and recommendations

This review examined the evidence and guidance available to inform practices around work adjustments for mental health at work. Alongside the growing focus on mental health at work, employers are being encouraged to prioritise the provision of work adjustments for employees with mental ill-health. While a number of work adjustments are reported to be beneficial to employees with mental ill-health including flexible working, time off for appointments, quiet workspaces, and adjustments to roles and responsibilities, the evidence to inform practices around work adjustments for mental health at work is in its infancy.

To ensure that employees are able to access work adjustments, and that where these are accessed they are of benefit to both the employee and organisation, there is need to: to develop a clear picture of current practices in the UK; enhance the guidance available to employees, colleagues, managers and professionals working within occupational health and human resources; and build the evidence base for work adjustments for mental health. The following actions are recommended:

1. Develop a clear picture of current practices in the UK

There is need to understand the experiences of employees with mental ill-health accessing work adjustments and of those wishing to access adjustment but are unable to do so. There is also need to understand the roles, responsibilities and experiences of the different stakeholders involved in facilitating access to work adjustments for employees. This could be achieved by:

- introducing more specific questions about mental health and work adjustments into a wider national survey such as the BITC Mental Health at Work survey or the Office of National Statistics to develop a picture of the prevalence of the use of specific work adjustments in the UK

- a large scale survey of employees with mental ill-health to understand the number of people with mental ill-health currently working with the benefit of adjustments; what specific adjustments are being implemented; how adjustments are accessed and implemented; and how adjustments are monitored and reviewed in practice – a survey could also enable a more granular analysis of the work adjustments used by employees with different mental health conditions, severity of mental ill-health, working within different sectors and job roles, and whether the employee has accessed adjustments within or outside of the Equality Act

- a large scale survey of employers, occupational health, human resources, and other professionals working to support employees with mental ill-health to understand the pathways used by employees to access work adjustments, the nature of the recommendations made and the experiences of working with professionals from other disciplines, line managers and the employee within the context of the health and social care provisions available to employees in the UK

2. Enhance guidance available to employees, colleagues, managers and professionals

There is very little guidance available to enable employees and others involved in the process of accessing and implementing work adjustments. Drawing from the review of the evidence the following could enhance the guidance currently available:

- provision of mirrored versions of guidance for different stakeholders whereby guides are underpinned by the same information, processes and frameworks but specifically tailored for the employee, colleague, manager and professionals working to support. This could improve the clarity and consistency in the advice provided and adherence to best practice principles

- clarification of the pathways to access work adjustments and the roles and responsibilities of those involved to provide employees and managers with a clear understanding of how work adjustment can be accessed, who to turn to for support and how to monitor and review adjustments

- include an overview of the barriers and facilitators to accessing work adjustments to encourage due consideration of the issues. This could optimise the likelihood that the work adjustments will be successful in helping the employee manage their work and health, and at the same time work for the team, manager and organisation

- focus on the relational aspects of the implementation of work adjustments – employees note the importance of feeling supported yet employers and human resource professionals tend to focus on the tasks and processes involved; an increased focus on the relational aspects could help employees to feel more confident in accessing and using the work adjustments afforded to them

- inclusion of checklists and exercises to help employees and those involved in the provision of work adjustments prepare, implement and review how the work adjustment is working for the employee, the team, manager and organisation – by providing a framework to guide behaviour change this more active approach could build on the raised awareness of the issues to encouraging action

- refer to the AGREE framework to identify ways to improve the transparency, engagement and standardised implementation of guidelines. In areas of healthcare it has been shown that guidance material that considers the scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability (including barriers and facilitators to its application), and editorial independence can help improve health outcomes – while not all components are practicable in all work settings, it offers a useful starting point from which to identify future developments to improve work guidance; a longer-term recommendation is to ensure that the guidance draws from the evidence base as it develops

3. Build the evidence base for work adjustments for mental health

The evidence base is in its infancy. While there is a reasonable body of research that describes the benefits of work adjustments there is a lack of evidence to demonstrate that work adjustments are associated with work and health outcomes, and a lack of evidence that specific work adjustments offer benefits over those afforded to a control group. The following steps are needed to test the outcomes of work adjustments:

Understanding colleague, team and line manager perspectives of work adjustments

Employees report that support and acceptance of the work adjustment from colleagues and line managers is helpful. However, little is known about their experience of supporting the employee or working within a team where a colleague has work adjustments. Interviews or focus groups with colleagues and line managers to elicit shared experiences of what works, what does not, and the impact of the work adjustment on their ability to manage their own work and health would be beneficial. Specifically, this could identify which work adjustments, under what circumstances, are easier for teams and managers to implement and maintain.

Longitudinal studies that follow employees who return to work following sickness absence over time (from initial absence to 18 months and beyond)

Incorporating qualitative and quantitative measures, would help us understand how employees access work adjustments, how adjustments are reviewed and change over time, and what benefits to health and work outcomes are accrued.

Robust designs using randomised control trials to test specific work adjustments

Where individuals who are afforded specific adjustments (for example flexible working) are compared to those who are not are needed. Such studies would provide valuable information about the efficacy of the work adjustments. Realist or process evaluation of the implementation and maintenance of work adjustments run alongside could provide in-depth understanding of the factors that influence whether a work adjustment is successful or not and map longer term change. By gathering information at multiple time points over the course of the time that the employee uses the work adjustment it would be possible to develop a more complete picture of the barriers and facilitators to implementing work adjustments.

There are a number of ways employees with mental ill-health can be better supported to access and implement work adjustments. To move forward, we need to develop a clear picture of current practices in the UK, enhance the guidance available and build the evidence base for work adjustments for mental health. It is important to note that the lack of evidence does not mean they do not work, it just means we do not have evidence that they work as yet, this may be partly due to the fact that evaluations being undertaken by employers on the impact of any workplace adjustment practices are rarely published or shared externally. As we build this evidence base, there is need for a co-ordinated multi-disciplinary approach, involving employees, managers, and professionals working across mental health, occupational health and human resources. This way we will ensure that employees with mental ill-health are afforded clear and consistent advice, in a way that is timely, supportive and enables them to better manage their mental health and maintain their ability work.

5. Appendices summary

The appendices are provided in an accompanying document.

1. Detailed methodology

1.1 Summary of Rapid evidence review extended methodology

1.2 Table 1: Inclusion criteria

2. Search terms and hits

2.1 Table 1: Search terms used in the review

2.2 Table 2: Hits found in ABI/Inform and Business source databases

2.3 Table 3: Hits found in the Cochrane Library

3. NESTA Standards of evidence

4. UK Stakeholder organisations included in the search

5. Agree framework for evaluating rigour of guidance

6. Summary of work adjustments referred to in guidance and evidence

6.1 Table 1: Work adjustment mapped against guidance, research reports and academic papers

6.2 Table 2: Adjustment term used within peer reviewed papers, research reports and guidance

6.3 Table 3: Adjustment noted in peer reviewed papers, reports and guidance classified under the work adjustment term

7. Summary of evidence reviews

7.1 Table 1: Summary of systematic reviews

7.2 Table 2: Summary of over-time studies

7.3 Table 3: Summary of survey design studies

7.4 Table 4: Summary of interview design studies

7.5 Table 4: Summary of research reports

6. References

6.1 Academic peer reviewed papers included in this review

A1

Dibben P, Woo G, Rachel O’Hara, 2018. Do return to work interventions for workers with disabilities and health conditions achieve employment outcomes and are they cost effective? A systematic narrative review. Employee Relations 40, 999–1014.

A2

Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, Clay F, Gensby U, Jennings, PA, Hogg-Johnson S, Kristman V, Laberge M, McKenzie D, Newnam S, Palagyi A, Ruseckaite R, Sheppard DM, Shourie S, Steenstra ID Van Eerd, Amick BC, III, 2018. Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions in Return-to-Work for Musculoskeletal, Pain-Related and Mental Health Conditions: An Update of the Evidence and Messages for Practitioners. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 28, 1–15.

A3

Mcdowell C, Fossey E, 2015. Workplace Accommodations for People with Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 25, 197–206.

A4

Nevala N, Pehkonen I, Koskela I, Ruusuvuori J, Anttila H, 2015. Workplace Accommodation Among Persons with Disabilities: A Systematic Review of Its Effectiveness and Barriers or Facilitators. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 25, 432–448.

A5

Vilsteren M van, Oostrom SH van, Vet HC de, Franche R-L, Boot CR, Anema JR, 2015. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

A6 Nieuwenhuijsen K, Faber B, Verbeek JH, Neumeyer‐Gromen A, Hees HL, Verhoeven AC, Feltz‐Cornelis CM van der, Bültmann U, 2014. Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

A7

Silva AA, Fischer FM, 2012. Teachers’ sick leave due to mental and behavioral disorders and return to work. Work 41, 5815–5818.

A8

Kools L, Koning P, 2019. Graded return-to-work as a stepping stone to full work resumption. Journal of Health Economics 65, 189.

A9

Streibelt M, Bürger W, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bethge M, 2018. Effectiveness of Graded Return to Work After Multimodal Rehabilitation in Patients with Mental Disorders: A Propensity Score Analysis. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 28, 180–189.

A10

Wåhlin C, Ekberg K, Persson J, Bernfort L, Öberg B, 2013. Evaluation of Self-Reported Work Ability and Usefulness of Interventions Among Sick-Listed Patients. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 23, 32–43.

A11

Villotti P, Corbière M, Fossey E, Fraccaroli F, Lecomte T, Harvey C, 2017. Work Accommodations and Natural Supports for Employees with Severe Mental Illness in Social Businesses: An International Comparison. Community Mental Health Journal 53, 864–870.

A12

Andrén D, 2014. Does Part-Time Sick Leave Help Individuals with Mental Disorders Recover Lost Work Capacity? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 24, 344–60.

A13

Tremblay CH 2011. Workplace accommodations and job success for persons with bipolar disorder. Work 40, 479.

A14

Peters H, Brown TC, 2009. Mental Illness at Work: An Assessment of Co-worker Reactions. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences (Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences) 26, 38–53.

A15

Mellifont D, Smith-Merry J, Scanlan JN, 2016. Disabling accommodation barriers: A study exploring how to better accommodate government employees with anxiety disorders. Work 55, 549.

A16

Mellifont D, Smith-Merry J, Scanlan JN, 2016. Pitching a Yerkes–Dodson curve ball?: A study exploring enhanced workplace performance for individuals with anxiety disorders. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 31, 71–86.

A17

Bastien M-F, Corbière M, 2019. Return-to-Work Following Depression: What Work Accommodations Do Employers and Human Resources Directors Put in Place? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 29, 423–432.

A18

Negrini A, Corbière M, Lecomte T, Coutu M-F, Nieuwenhuijsen K, St-Arnaud L, Durand M-J, Gragnano A, Berbiche D, 2018. How Can Supervisors Contribute to the Return to Work of Employees Who have Experienced Depression? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 28, 279–288.

A19

Jansson I, Gunnarsson AB, 2018. Employers’ views of the impact of mental health problems on the ability to work. Work 59, 585–598.

A20

Peterson D, Gordon S, Neale J, 2017. It can work: Open employment for people with experience of mental illness. Work 56, 443.

A21

Lemieux P, Durand M, Hong QN, 2011. Supervisors’ Perception of the Factors Influencing the Return to Work of Workers with Common Mental Disorders. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 21, 293–303.

6.2 Research reports included in this review

R1

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2019). Managing long-term sickness and incapacity for work. Manchester (UK): National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

R2

Mental Health at Work Report. (2019). Chartered Institute of Personnel Development. London.

R3

Mental Health at Work: Time To Take Ownership. (2019). Business in the community. London.

R4

Farmer P and Stevenson D (2017). Thriving at Work: The Independent Review of Mental Health and Employers (viewed on 12 November 2017).

R5

Joosen MWC, Arends I, Lugtenberg M, Timmermans JAWM, Bruijs-Schaapveld BCTM, Terluin B, ... and Brouwers EPM (2017). Barriers to and facilitators of return to work after sick leave in workers with common mental disorders: Perspectives of workers, mental health professionals, occupational health professionals, general physicians and managers. Institute of Occupational Safety and Health: London.

R6

Hudson M (2016). The management of mental health at work. Research report for Acas Ref: 11/16. ISBN 978-1-908370-73-0

R7

Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare in BC. (2010). Best practices for return-to-work/stay-at-work interventions for workers with mental health conditions: final report. Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare in BC: Vancouver.

R8

Blisker D and others (201?). Depression and work functioning: Bridging the gap between mental health care and the workplace. The depression in the workplace collaborative: Canada.

6.3 Additional references

Norder G, van der Ben, CA, Roelen CA, Heymans MW, van der Klink JJ, and Bültmann U (2017). Beyond return to work from sickness absence due to mental disorders: 5-year longitudinal study of employment status among production workers. European journal of public health, 27(1), 79-83.

NHS Digital (2017). Fit notes issued by GP practices, England, December 2014 to March 2017 (viewed on 15 December 2019)

McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T (editors) (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. Leeds: NHS digital.

6.4 Guidance material included in this review

G1: Acas Common adjustments for staff experiencing mental ill health

G2: Access to work fact sheet for employers

G3: BITC Mental health toolkit for managers

G4: BITC Mental health toolkit for organisations

G5: BUPA Supporting employees with mental health problems

G6: CIPD MIND Managing and supporting mental health at work disclosure tools for managers 2011

G7: CIPD MIND People managers guide to mental health 2018

G8: DH Advice for employers on workplace adjustments for mental health conditions

G9: DWP Employing disabled people and people with health conditions

G10: Heads Together Mentally Healthy Schools

G11: HSE Managing sickness absence guide for managers and employees

G12: IAPT NHS Berkshire self help resources

G13: MHF UNUM Managing mental health in the workplace

G14: MHFA Line Manager Resource

G15: Mind - How to support staff who are experiencing a mental health problem

G16: Mindful Employer - Making Work Work

G17: Rethink Mental Illness - What's reasonable at work

G18: Scottish Association for Mental Health Reasonable Adjustment Booklet

G19: Shift DH HSE DWP Line managers guide to mental health 2007

All URL links were viewed on 6 November 2019.