Disclaimer

This report was prepared for Acas by:

Bernard Steen, Martin Mitchell, Katy Robertson, Conor O’Shea, Charlotte Lilley and Joe Killick from the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen).

The views in this research paper are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the authors alone. This paper is not intended as guidance from Acas.

Executive summary

Acas collective conciliation aims to resolve employment disputes between employers and groups of employees, the latter typically represented by trade unions.

The service has experienced several changes over recent years. Overall use of the service has declined for several decades, reflecting wider trends such as the growth in the statutory individual employment rights framework and the reduced incidence of collective bargaining. But more recently there has been an increase in use of collective conciliation, which has occurred alongside an uptick in industrial action in 2022 and 2023, as well as growing cost of living pressures and high inflation. Additionally, the covid-19 (coronavirus) pandemic prompted the service to shift away from in-person to online delivery, and it now operates using a hybrid model.

Collective conciliation was last evaluated in 2016, looking at cases that were conciliated in 2014 to 2015. This report presents the results of a new evaluation of the service, looking at cases that took place in 2022 to 2023. It assesses how the service is being delivered, whether it is achieving its intended impacts, and what improvements could be made.

The new evaluation is based around a Theory of Change, which sets out how the collective conciliation service is expected to bring about its intended outcomes and impacts. The service was assessed against the outcomes and impacts identified in the Theory of Change by conducting both a survey of 241 collective conciliation customers who had used the service in 2022 to 2023, and in-depth qualitative interviews with 26 of these customers.

What is the operating context for collective conciliation, and how effectively is the service being delivered?

In general, conciliators remain highly regarded by customers. For example, 93% of customers agreed that their conciliator was trustworthy, and 91% agreed they were impartial. However, employee representatives feel more positively about conciliators than do employers, which is unchanged since 2014 to 2015.

The hybrid delivery model broadly seems to be working well. Initial conversations generally take place online or by phone, whereas the vast majority of conciliation talks have returned to in-person delivery, post-pandemic. Customers generally felt this balance was appropriate. However, not all customers were offered an online option, the possibility of which they would have liked to be made clearer.

In 2022 to 2023, the nature of the disputes coming to the collective conciliation was substantially different than in 2014 to 2015. Three-quarters of disputes in 2022 to 2023 (74%) were about pay, compared to under half (46%) of disputes in 2014 to 2015. In large part, this appears to be driven by the increased cost of living, with three-fifths of all customers (61%) citing cost of living as a factor in their dispute.

In qualitative interviews, customers described how the initial positions of the parties in these pay disputes were far apart, meaning that disputes escalated quickly and that both parties felt a sense of urgency to resolve the dispute as soon as possible. More of the disputes that are coming to Acas have already involved industrial action, or the threat of industrial action, or a ballot on it.

An increased proportion of customers have referral to Acas as part of their written procedures, and the findings suggest that for some customers the conciliation process is more of a procedural and administrative exercise than a genuine attempt at dispute resolution.

What are the outcomes and impacts of the collective conciliation service?

In general, the service was performing similarly compared to 2014 to 2015. The proportion of disputes that reached a settlement was unchanged: for over half of disputes (58%), customers felt the key issues had been settled, for 16% of disputes customers felt some progress was made, and 1% of disputes went on to arbitration. Taken together, it follows that three-quarters of all customers judged that their dispute was settled or progressed.

Most customers remained satisfied with the service: 73% rated it 6 or 7 out of 7 (where 1 is the lowest, and 7 the highest level of satisfaction). And of those customers whose dispute was resolved, most (87%) felt that Acas played an important role in bringing about a positive resolution (4 or 5 out of 5, where 5 is 'very important').

The most important factors linked with customer satisfaction were the outcome itself, how long it took to achieve it, and the extent to which conciliators were able to move parties towards an understanding of each other's positions and, eventually, a compromise.

The qualitative interviews also show that aftercare – ongoing contact after the conciliation process has ended, including efforts to improve relations between parties for the future – was important and was associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction. However, aftercare could perhaps be offered to customers more routinely to help on-going improvement in workplace relations.

Longer-term improvements in organisations as a result of participating in conciliation were relatively modest, consistent with the 2014 to 2015 findings, and customers indicated that this might be related to somewhat low levels of aftercare.

The evidence suggests that the change in the nature of the disputes reaching Acas (an increasing number of relatively difficult pay disputes due to inflationary pressures and their effect on wage negotiations) has not led to lower levels of dispute resolution or satisfaction with the service, which is positive.

However, interviewees indicated that this is likely to lead to more disputes re-occurring and potentially returning to Acas, as solutions are more likely to be short-term than they used to be. In 2022 to 2023, 66% of customers involved in disputes where an agreement was implemented, agreed it resolved the dispute in the long term, down from 76% in 2014 to 2015.

What lessons can be learned to inform future service delivery?

The qualitative evidence suggests that most of the potential service improvements relate to preparatory work done before conciliation meetings begin, and in the aftercare provided after conciliation ends.

Prior to conciliation, there is potential for conciliators to do more to prepare themselves and the parties. This could involve doing more to understand the positions of the parties, and in particular to explore where there is the potential for compromise. This is particularly important given the increased number of pay disputes, where there is a wider and more sustained gap between the parties.

Conciliators could do more to explain how the process will unfold, particularly for employers who are less likely to have experience of the service. They could also do more to explain to the parties that conciliation is unlikely to help if there is no willingness to compromise, and to explain what compromise could look like in practice.

After conciliation, there is potential for more standardised aftercare processes, involving follow-up contact with both sides. This could involve conversations with the individual parties but could also involve formal sessions with both sides to discuss working relationships without a pressing dispute to deal with. This has the potential to help with ongoing employment relations, reducing the likelihood that disputes will reoccur and increasing satisfaction with the service.

More generally, it remains the case that employers – compared to employee representatives – are generally less experienced with the service, less satisfied with it, less likely to receive follow-up contact, and less likely to feel it has led to ongoing improvements.

There is a risk that conciliators are better able to relate to and communicate with employee representatives than they are with employers. This was because conciliators and most employee representatives are employment relations professionals, whereas some employers and managers are very often not. Acas could consider whether there is a need for more proactive engagement with employers throughout the process.

1. Introduction

Collective conciliation is a statutory service provided by Acas for resolving collective employment disputes between employers and groups of employees (typically represented by a trade union) through facilitated or assisted negotiation. The service is free, voluntary and confidential.

This report presents the results of an evaluation of collective conciliation. It assesses how the service is being delivered, whether it is achieving its intended impacts, and what improvements could be made.

1.1 Background to the evaluation

The use of collective conciliation has changed over recent decades. Overall use of the service has declined, reflecting a decline in formal collective disputes and a move towards workplace conflicts that present individually.

Acas has identified a range of reasons for this, including the growth in the statutory individual employment rights framework, decline in union membership, reduced incidence of collective bargaining as well as declining experience among HR and employee representatives of collective disputes (see Adam D et al (2024) Continuity and change in collective workplace conflict in Britain: A classification of contemporary actors, issues and channels, Acas research paper).

However, there has been a recent increase in collective conciliation requests. In 2022 to 2023, there were 621 requests, up from 500 in each of the previous 2 years. This occurred in the context of widespread industrial action from the summer of 2022, and a sharp increase in the cost of living due to rising inflation.

Alongside this, the service has had to adapt to the lasting changes brought about by the covid-19 (coronavirus) pandemic. Previously, the service had been delivered entirely in-person, but during 2020 and parts of 2021 the service was delivered entirely online. Since then, the service has been delivered using a flexible hybrid model, whereby certain aspects of cases may be handled online (for example, preliminary discussions) and others (for example, formal talks between the parties) happen in-person.

Collective conciliation was last evaluated in 2016, looking at conciliation cases that took place in 2014 to 2015. There was therefore a need to update Acas's understanding of how the service was performing, especially in the light of recent trends.

1.2 Research objectives

The aim of this research was to robustly evaluate the collective conciliation service. Within this, the research had some more specific aims to:

- provide an update on the 2016 evaluation by using comparable survey methods

- understand how the hybrid delivery model was working

- understand how the current employment relations and cost of living context was affecting the service

The research aimed to answer the following questions and sub-questions:

1. What is the context in which collective conciliation is operating, and how effectively is it being delivered?

- How do customers reach the collective conciliation service? What kinds of customers are using the service, and what kinds of disputes is the service seeing? How and why is Acas becoming involved in disputes?

- How well is the hybrid delivery model working?

- What are customers' perceptions of Acas conciliators?

2. What are the outcomes and impacts of the collective conciliation service?

- How satisfied are customers with the service?

- To what extent does collective conciliation help to resolve disputes, in both the short-term and the long-term?

- To what extent does the service improve employment relations?

- Does the service support customers' ongoing development? Does it lead to changes with organisations?

3. What lessons can be learned from the evaluation for the future development and improvement of the collective conciliation service?

This report answers these research questions over the course of the next 3 chapters. Chapter 2 describes the operating context within which the collective conciliation service is being delivered, answering research questions 1a to 1c. Next, chapter 3 answers research questions 2a to 2d by exploring the impacts and outcomes of collective conciliation. Finally, chapter 4 addresses research question 3 and summarises lessons for service development.

1.3 Research methods

The research involved 3 main elements.

A Theory of Change for the collective conciliation service

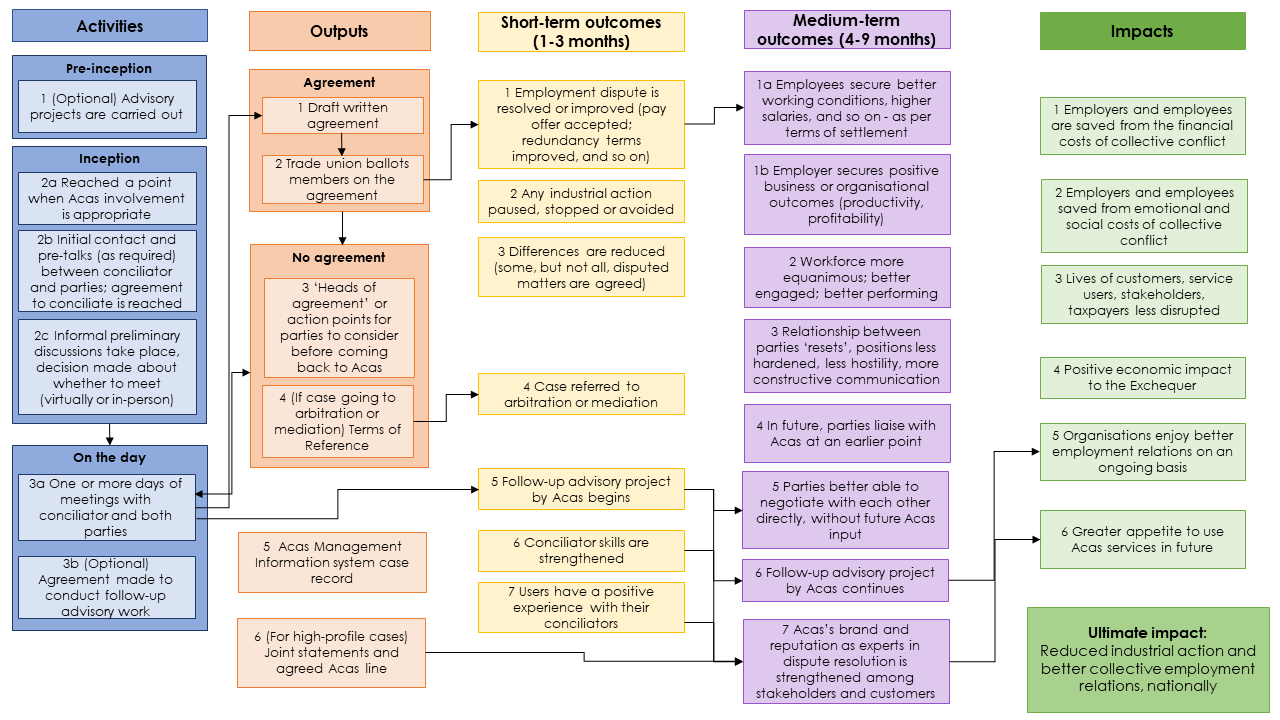

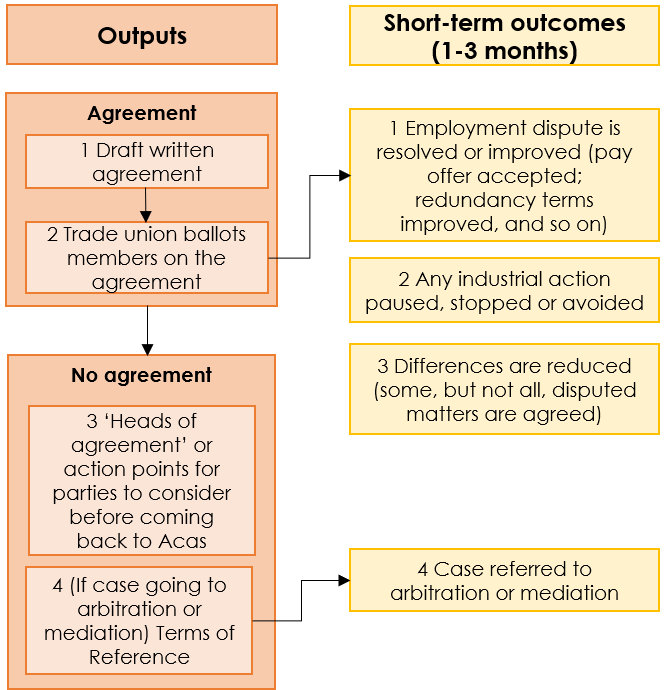

A Theory of Change (Figure 1) was developed for the collective conciliation service.

This sets out how a service is expected to bring about its intended short- and medium-term outcomes, and its intended longer-term impacts. It does this by spelling out each step in the causal process, alongside the assumptions that must hold for one step to lead to the next.

By designing the data collection and analysis around the Theory of Change, we can determine the extent to which it accurately describes a real causal process.

This enables more robust conclusions about the extent to which the collective conciliation service is achieving its aims. Relevant sections of the Theory of Change have been added throughout the report, appearing alongside the findings they relate to.

A survey with collective conciliation customers

A survey was conducted with collective conciliation customers who had used the service between April 2022 and September 2023.

All 730 customers who used the service in that time – both employers and employee representatives – were invited to take part, and 241 did so, giving a response rate of 33%.

The survey was conducted online and by phone, and largely replicated the questionnaire used in the 2016 evaluation, with some changes. Customers were primarily asked to reflect on their most recent dispute involving Acas, including the nature of the dispute, the reason they involved Acas, how the dispute unfolded, the outcome, and their views on the process, among other topics.

Responses have been weighted to ensure that employers and employee representatives are given equal weight in the analysis. Throughout this report, differences between groups of customers, and differences between 2014 to 2015 and 2022 to 2023, are only reported if they are statistically significant at the 95% level.

Qualitative interviews

Qualitative interviews with 26 customers were conducted online or by telephone, including 14 interviews with employers and 12 with employee representatives.

Customers were selected to ensure a range of sectors, organisation sizes, prior experience with the collective conciliation service, and different levels of satisfaction with the service.

The qualitative findings reported in this evaluation have been included to give insight into the factors that are driving and shaping the trends that are revealed by the quantitative analysis of survey responses.

Together both types of data give a more holistic and comprehensive view of trends and issues identified in the study. The quotes from the interviews included in this report are followed by information about the type of customer who provided it, where 'R' represents employee representatives and 'E' represents employers.

More detail on the research methods, including the full Theory of Change with assumptions, is provided in the technical report.

A full text description of the Theory of Change is available in Appendix 1

2. What is the operating context for collective conciliation and how effectively is the service being delivered?

This chapter begins by looking at what happens before collective conciliation starts:

- the kinds of organisations that are coming to Acas

- the types of disputes they are experiencing

- the state that these disputes have reached

It then explores how and why customers are approaching Acas. Lastly, it considers the effectiveness of the service by looking at the hybrid delivery model, and customers' perceptions of conciliators.

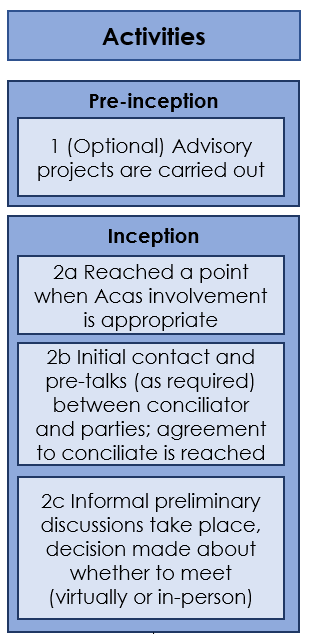

As shown in Figure 2, these findings relate to the first 4 stages of the Theory of Change. Initially, advisory work may take place even before conciliation begins. This is followed by 3 key activities that happen at the point of a case's inception:

- first, the point at which Acas involvement becomes appropriate is reached

- initial contact and pre-talks between the conciliator and parties then take place, leading to an agreement to conciliate

- informal preliminary discussions happen next, with decisions made about whether to meet (either virtually or in person)

2.1 How do customers reach the collective conciliation service?

This subsection looks at the profile of customers, the types of disputes, and how and why Acas becomes involved in them.

2.1.1. What kinds of customers are using the service?

Section summary:

- The profile of users in 2022 to 2023 was similar to the profile in 2014 to 2015, when the service was last evaluated.

- Most disputes again involved private sector organisations.

- There was a slight increase in 2022 to 2023 in the proportion of customers who were using Acas collective conciliation for the first time, and in the proportion of customers who came to Acas because doing so was part of their formal procedures for handling collective disputes.

Employers and the workforce

Most conciliated disputes occurred in the private sector (68%), compared to 22% that involved a public sector workplace, and 10% that involved a voluntary or not-for-profit sector workplace.

It was more common for Acas to conciliate between disputing parties in workplace disputes that only involve single workplaces: 44% of disputes involved a single independent workplace not belonging to any other organisation (a slight increase from 32% in 2014 or 15), 26% involved one workplace that belonged to a multi-site organisation, and 30% of disputes involved multiple workplaces belonging to the same organisation.

Size of the employer

Most employers that used the service were large: median total organisation size was 1,000 employees across all sites, and 79% of organisations using conciliation had at least 250 employees.

Employers were also asked how many staff were working across just the workplaces covered by the dispute, and the median figure reported was 250.

Level of unionisation

Two-thirds (64%) of organisations involved in conciliated disputes had trade union density rates above 50%, which is an increase from 53% in 2014 to 2015. This is also notably higher than the rate of trade union membership among UK employees overall, which stood at 22% in 2022 (find out more about trade union membership statistics (PDF, 664KB) from the Department for Business and Trade statistical bulletin 2023).

There was a difference in how employer and employee representatives perceived the levels of unionisation in the organisations involved in the disputes. Employee representatives were more than twice as likely to report that 75% or more of the workforce were union members compared with employers (42% compared to 17%), which could suggest that employers were underestimating union membership, or that union membership increased significantly after disputes ended.

Customers' prior experience of collective disputes and collective conciliation

For half of customers (50%), the dispute that Acas handled was the only collective dispute at the organisation in the last 3 years. A third of organisations (33%) had experienced 2 or 3 collective disputes in that period, and 1 in 6 (17%) had experienced 6 or more.

In 2022 to 2023, 40% of employers using the service were doing so for the first time. This was a slight increase from 32% in 2014 to 2015. Across both waves, employers were much more likely to be first time users: in 2022 to 2023, 47% of employers were first time users, compared to just 18% of employee representatives.

First-time users typically came to the collective conciliation service because they were experiencing their first ever collective dispute (64% of first-time users). However, over a third of first-time users (36%) had experienced a collective dispute before but came to Acas on this occasion because talks within their organisation had broken down completely for the first time. These figures were similar in 2014 to 2015.

In qualitative interviews, employers described using Acas for the first time because a strike was already underway, because a legal consultant recommended the service, or because they were party to a (group) claim to an employment tribunal and had been contacted directly by Acas.

These findings suggest that a good number of organisations experiencing their first difficult collective dispute are coming to Acas for help. But without data on the number of organisations in similar circumstances that are not coming to Acas, we cannot assess quantitatively whether Acas is successfully reaching potential first-time users.

Formal procedures for collective disputes

Most customers (85%) had formal procedures for dealing with collective disputes, which was unchanged from 2014 to 2015. This figure was lower for first time users, 74% of whom had formal procedures, compared to 90% of repeat users.

Of those customers with formal procedures, an increased share had referral to Acas written into these procedures: 82%, up from 69% in 2014 to 2015. While this is a positive finding, one implication may be that referral to Acas is increasingly seen as a procedural step, rather than a deliberate and strategic commitment to try to resolve workplace disputes. This particularly reflected that some parties were involving Acas because of higher inflation, the increased cost of living and associated effects on wage negotiations, sometimes for the first time, or the first in years.

Section 2.1.3. further explains how the most common reason given by customers for using Acas conciliation was that Acas conciliation is part of the organisation's dispute procedure.

2.1.2. What kinds of disputes is the service seeing?

Section summary:

- There was a clear increase in the proportion of disputes that were about pay. In most cases this was related to the current cost of living, which tended to factor into pay disputes.

- Compared to 2014 to 2015, the disputes that came to Acas were more likely to have involved industrial action, the threat of industrial action, or ballots on industrial action.

Dispute causes

The main issue at stake in most disputes was pay (74%), which was a marked increase from 46% in 2014 to 2015. The other main issues at stake were trade union recognition (18%) and terms of employment (other than pay) (18%; down from 26% in 2014 to 2015). There were no other notable changes in the types of issues at stake in the disputes coming to Acas.

Two new questions were added to the 2023 wave of the survey, asking customers whether the dispute was related to either the increased cost of living or any changes that the organisation had made because of the covid pandemic.

Disputes were said to be a direct result of the increased cost of living by 18% of customers; a further 43% said that the cost of living had been a factor in the dispute. This was a consistent theme in qualitative interviews, and employee representatives explained how their members expected higher pay increases to cope with the increase in the cost of living.

Conversely, organisational changes made following the covid pandemic were not seen as a factor for most disputes: 90% of customers said that the dispute "was not related to any changes made as a result of the pandemic".

The state of disputes when Acas becomes involved

Acas tended to become involved in disputes after several attempts to reach an agreement had already been made (36%), when a deadlock had been reached between the parties (21%), when a crisis point had been reached in negotiations (21%), or when a first failure to agree was registered (7%). These figures were similar in 2014 to 2015.

In 2022 to 2023, disputes reaching Acas were more likely to have already involved industrial action, a ballot on industrial action, or the threat of industrial action, prior to Acas' involvement (63%) than was the case in 2014 to 2015 (48%). Furthermore, in 2022 to 2023, of those disputes that had not already involved industrial action, a ballot on it, or the threat of it, 31% of customers felt there was a risk of industrial action – compared to just 18% in 2014 to 2015.

Of those who had threatened to take, or had balloted on industrial action, or who felt there was a risk of (further) industrial action at the time of Acas involvement, 94% said that the potential industrial action in question would involve a strike or stoppage, compared to 76% in 2014 to 2015. Taken together these findings indicate that industrial action has become a more prominent pre-existing feature of disputes reaching Acas.

In 2022 to 2023, dispute negotiations had also been ongoing for less time prior to Acas involvement than was the case in 2014 to 2015 – in other words, the dispute was newer at the point of Acas becoming involved. This is likely related to the increase in pay disputes related to the cost of living. Two-fifths (42%) of disputes in 2022 to 2023 had already been in negotiations for between 4 and 6 months before Acas became involved, with a further 20% that had been in negotiations for over 7 months. By comparison, in 2014 to 2015, only 30% of disputes had been in negotiations for between 4 and 6 months, whereas a further 28% had been in negotiations for over 7 months.

Qualitative interviews reveal there was a sense of urgency around pay disputes, with both employer and employee sides under pressure to reach an agreement quickly. Because the parties were often far apart in their expectations for a settlement, disputes were escalated rapidly.

In pay disputes that were related to the cost of living, there was a wider, more sustained gap between the demands of the workforce on pay and the pay offers from management when compared to non-pay disputes. One employee representative described how this escalation in expectations occurred in their dispute:

This tended to result in disputes escalating further and faster – up to the eventual point of using Acas's collective conciliation service, because employers and employee representatives felt that internal negotiation options were being quickly exhausted.

However, some customers placed less emphasis on the impact of recent cost of living pressures on how pay disputes were conducted. Some employers and employee representatives said tensions during pay disputes and failures to agree between them was not unusual. Instead, they were described as routine and expected.

Around half of customers felt that it would not have been beneficial to involve Acas at an earlier stage in the dispute (55%). Almost a third felt it possibly would have been beneficial (31%), and 14% felt it definitely would have been beneficial. Employee representatives were more likely to think that it would have definitely been beneficial to involve Acas earlier: 19% of employee representatives felt this way, compared to 8% of employers – a difference that remained significant after controlling for dispute outcome.

Of those customers who felt it would have been beneficial to include Acas at an earlier stage, the most common reason for not doing so was that they had not exhausted their dispute procedures or did not think the dispute had progressed far enough (77%).

The relationship of the parties

At the time when Acas conciliation was about to begin, 36% of customers felt the relationship with the other party was poor, whereas 32% felt it was good. This was similar in 2014 to 2015. Employee representatives had fewer positive views on relationships: 48% described the relationship as poor, compared to 25% of employers, and again this was similar in 2014 to 2015.

In qualitative interviews, employee representatives and some employers described increased tensions between staff, unions, and management due to the recent impact of high inflation, the increased cost of living and subsequent pressure placed on pay negotiations. Relations were described as more tense compared to the past when approaching Acas. One employee representative, reflecting on his previous experiences compared to now, said:

However, other employers thought that pay disputes were routine, with some tension always expected as part of negotiations. They said this was no different to the past, and workplace relations had remained good.

Willingness to move position

As in 2014 to 2015, most customers were prepared to move a little from their initial position going into conciliation (63%), whereas just 10% were prepared to make significant movement to reach an agreement. Very few were opposed to a conciliated agreement of any kind (2%), but 17% were only interested in an agreement if new options were offered. Compared to 2014 to 2015, there was a slight shift away from the parties requiring new options to be offered in order to reach an agreement, towards being willing to move a little from their initial positions to do so. Employers were more likely to be prepared to move a little from their initial positions (69%) than employee representatives (57%).

In qualitative interviews, one group of customers did not believe it was possible for them to concede any further on terms of the dispute and insisted they had gone as far as possible to find an agreement at the point of Acas's involvement. Instead, whilst not always stated explicitly, it was implied in these situations that it was the responsibility of the other side to reflect and move their position, sometimes reflecting an employer's or union's wider negotiating position. In one case a participant said:

These customers hoped an independent conciliator would encourage the other party to compromise, even though this is a misunderstanding of the conciliator's role. They chose to involve Acas to demonstrate to employees that their party was doing all that was possible, to progress to other processes (for example, group tribunal claims), or because they felt that it could not be damaging so worth a chance despite low expectations. While the parties were sometimes willing to make small compromises, one or both parties' positions tended to remain entrenched. Where movement was sometimes achieved this could be at the expense of one party feeling bullied into submission by the other (see section 3.2.1).

However, another group of customers were more open to reviewing their position and felt that a conciliator would help them to do that by highlighting factors that either party had not yet considered. These customers felt that having an independent party present could act as a helpful check on whether each side was being reasonable in their expectations. Acas offered a chance for self-reflection for them as well as by the other party in the pursuit of a settlement. One participant belonging to this group said:

2.1.3. How and why is Acas becoming involved in disputes?

Section summary:

- Customers generally involved Acas in their dispute because they felt unable to resolve it themselves and wanted to reach an agreement.

- Many used Acas because doing so was part of their written procedures. Employers were more likely than employee representatives to reach out to Acas in the first instance and tended to do so via a generic helpline or email address.

- Where employee representatives made first contact, they were more likely to contact an individual conciliator, and were more likely than employers to have an existing contact at Acas.

As shown in Figure 3, the findings in this subsection relate to 2 key activities that happen at the stage of a case’s inception in the Theory of Change:

- first, the point at which Acas involvement becomes appropriate is reached

- initial contact and pre-talks between the conciliator and parties then happen, leading to an agreement to conciliate

Why do customers involve a third party?

Customers were asked why they had decided to involve a third party such as Acas in their dispute (and could select multiple reasons).

Most said it was because they had reached a point where the dispute could not be resolved between themselves (62%), or they wanted to reach an agreement with the other side (60%). More than half sought to involve a third party because it was the next step in their dispute procedures (54%), over a third to speed up the resolution of the dispute (37%), and around a third to avoid (further) industrial action (31%).

The most common reason given by customers for using Acas conciliation specifically was that it is part of the organisation's dispute procedure: 58% gave this as a reason, and 36% gave this as the only or main reason.

The qualitative interviews also showed that some employers and employee representatives would not have involved Acas were it not for their written procedures requiring it, and that some of them may not be entering the service with the same commitment to reaching a conciliated agreement as others. These customers may benefit from additional efforts by conciliators to prepare them for conciliation, and to make clear what is involved and expected.

The second most common reason was that Acas is impartial or independent of management and union: 56% gave this as a reason, and 32% gave this as the only or main reason. Around 4 in 10 said they involved Acas because they are acceptable to the management or employee side (40% and 41% respectively), but very few gave this as the only or main reason. Employee representatives were more likely to involve Acas because they are acceptable to their side: 47% of employee representatives involved Acas because they are acceptable to the employee side compared with 34% of employers. There was no statistically significant difference for Acas being acceptable to the employer side by customer type.

Qualitative interviews largely confirmed these findings. However, in some cases where the dispute involved the potential submission of a group claim to an employment tribunal, customers involved Acas because notifying Acas of their intention to make a claim was a required step in early conciliation process, even though participation is not compulsory. For example, one employee representative’s union oversaw the submission of a group tribunal claim against the employer because the latter had tried to circumvent a collective bargaining agreement.

What customers wanted to demonstrate by getting Acas involved

By bringing Acas into a dispute, both sides wanted to demonstrate to workers or members that they were seriously attempting to reach an agreement. 67% percent of employee representatives felt it was very important to demonstrate to their union or association membership that everything was being done to get them the best deal, and 65% of employers felt it was very important to demonstrate to their workers that they were trying to solve the dispute. In contrast, only 34% of employers felt it was very important to demonstrate to their customers that they were trying to resolve the dispute; 33% felt this about the business owners.

Only 21% of employers and 27% of employee representatives said that it was very important to demonstrate to the general public that they were trying to solve the dispute by bringing in Acas. This was consistent for both private and public sector employers.

How are customers making contact with Acas?

In most disputes (76%), initial contact with Acas was made by a single party. In 14% of disputes, the parties jointly made contact, and in 10% of disputes Acas made first contact. Employers were slightly more likely than employee representatives to make first contact with Acas. Where parties made first contact with Acas, this tended to be via a generic Acas telephone number (59%), but a third of those who made first contact (33%) did so with a specific conciliator. Of those cases where a specific conciliator was approached, most customers said that they approached them because they or the other party had worked with that conciliator before (76%).

Although getting in touch with an existing contact was ideal for those who had them, getting in touch with Acas via the website or their phone line was sometimes challenging. Customers who found making an initial contact an easy process said that Acas's website was easy to navigate and had no problems finding the correct phone numbers.

However, there were some issues when it came to customers, particularly first-time users, being referred several times to different conciliators after having completed an enquiry form via Acas's website. Those who found getting in contact challenging reported that the process of responding to them was slow, sometimes leading to resubmission of the form. They said the phone lines associated with the collective conciliation service or specific conciliators were so busy they were unable to get through for several days. Additionally, employee representatives with no prior experience of collective disputes or working with Acas said that the legal terminology required by the forms on the website made them difficult to complete.

Employers were more likely than employee representatives to use a generic telephone number or email address to initiate contact with Acas: 69% of employers who initiated contact with Acas did so using a generic telephone number or email address, compared to 49% employee representatives who contacted Acas. Conversely, 41% of employee representatives reported approaching a specific conciliator at Acas, compared to just 25% of employers. In qualitative interviews, those employers who reached out to a specific conciliator had generally been recommended the conciliator by someone else, such as the employee representative, or a legal consultant.

There were advantages and disadvantages to working with established conciliator contacts. Employee representatives and employers who had used the service before said they relied on established contacts with conciliators. The advantages of this approach were that it facilitated earlier and faster contact, and that they knew that the conciliators had good sector knowledge. For example, one employee representative reflected on the benefit of a specialised conciliator in their sector:

A disadvantage of using established contacts, however, was that employers sometimes felt that pre-existing relationships with employee representatives led to more one-sided conciliation. Employers thought conciliators may have had more contact with employee representatives during the earlier parts of conciliation. This is explained in more detail in section 2.3 and highlights perceptions of impartiality.

Could Acas improve awareness of the service?

Although both survey and qualitative fieldwork was conducted with employer and employee representatives who had used the service, and were therefore aware of it, these customers nonetheless had insights into how awareness could be improved.

One employee representative reflected that their colleagues, as well as other employers, don't work as closely or regularly with Acas as they did:

Employers felt more could be done to promote Acas and the collective conciliation service, including boosting the social media presence and organising more networking events. This could also involve working with organisations that support small and medium-sized businesses, as these were seen as having less awareness of Acas and the service, or convening groups of employers to inform them. For small and medium-sized businesses, the importance of collective conciliation being a free service was emphasised.

2.2 How well is the hybrid delivery model working?

Section summary:

- Overall, the hybrid delivery model appears to be working well.

- Customers generally preferred conciliation to take place in-person.

Since the pandemic, the service has been operating a hybrid model, with a flexible mix of online or telephone and in-person delivery.

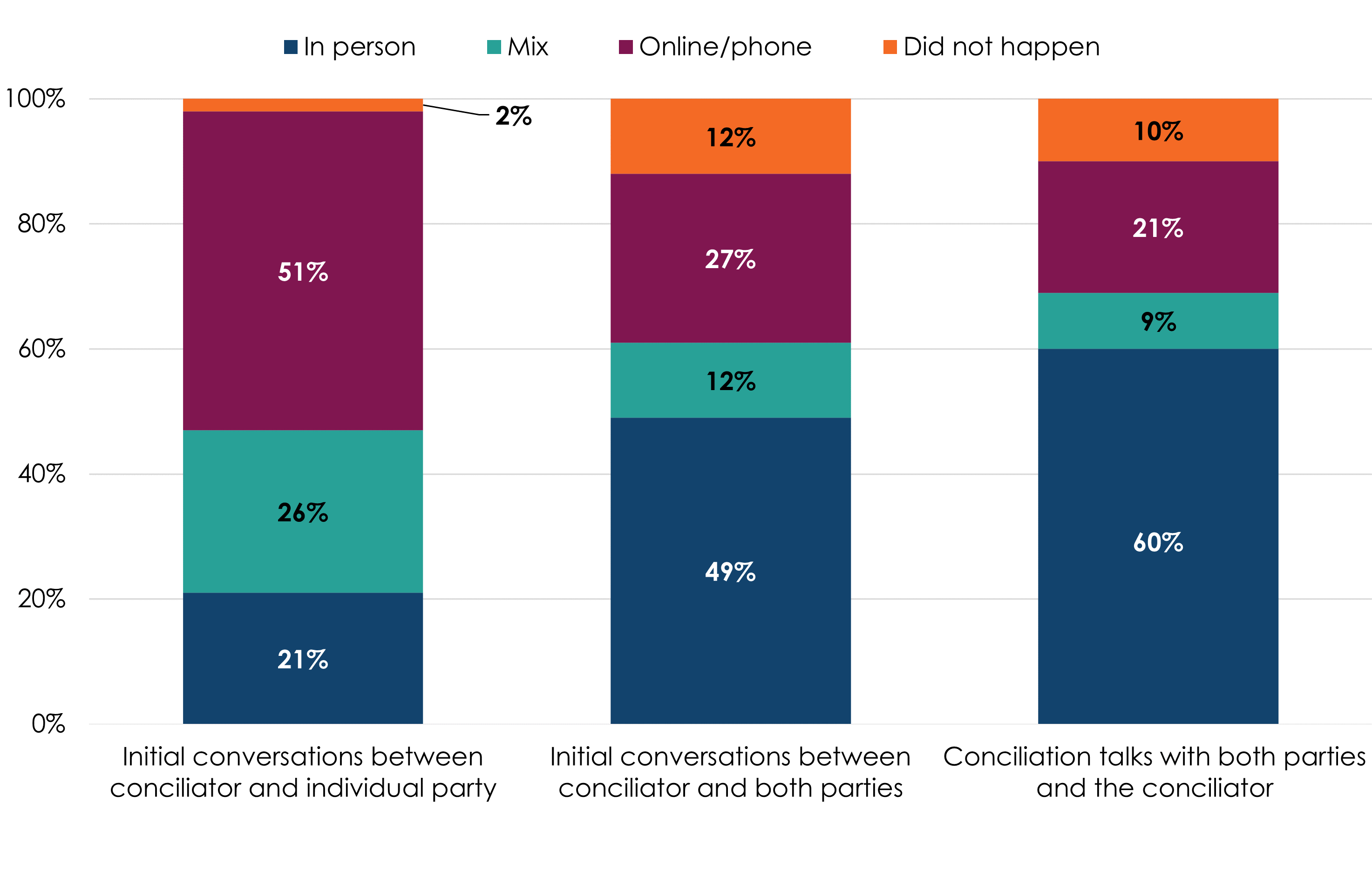

As of 2022 to 2023, most initial conversations between conciliators and individual parties in a dispute were happening online or by phone (Figure 4). For example, more than three-quarters (77%) of customers had initial conversations with the conciliator that were at least partly online or by phone, with around half (51%) doing so exclusively online or by phone. Most conversations involving both parties and the conciliator had returned to taking place in person; 69% of customers had conciliation talks at least partly in person, with three-fifths (60%) of conciliation talks happening exclusively in person.

Base: All customers (241). The legend is presented in the same order as the categories within the bars.

| In-person | Mix | Online or phone | Did not happen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial conversations between conciliator and individual party | 21% | 26% | 51% | 2% |

| Initial conversations between conciliator and both parties | 49% | 12% | 27% | 12% |

| Conciliation talks between both parties and conciliators | 60% | 9% | 21% | 10% |

However, in qualitative interviews, some customers did not recall being offered a choice, which they would have liked to be made clearer. While the overall preference was for face-to-face conciliation (especially at later stages in the process), this was not always the case. Those who preferred face-to-face conciliation gave 3 reasons:

- The weight it gave to the importance of the process – both employers and employee representatives thought that the effort to attend in person was greater than attending online, and therefore showed commitment to the process and to finding a resolution by both parties.

- It made it easier to read important body language – both employers and employee representatives said they thought there was greater honesty being face-to-face with the other party. For example, one employee representative said: "The cut and thrust of human interaction and emotion is incredibly important to me as a negotiator, so, and just doing it through a video on that, you lose that" (R4, public sector, smaller union, repeat customer).

- Concerns about confidentiality – customers also expressed concerns over confidentiality when it came to online delivery. There was a fear that the video call technology would fail, and the other party may be able to hear their confidential discussions.

While there were still some lingering concerns with face-to-face conciliation due to the risk of covid-19 infection post-pandemic, this was rare. Instead, there were now 2 main reasons for some customers preferring online contact:

- Convenience when parties where geographically spread – in-person delivery could involve substantial time and expense. This was especially when employers were multi-site, or employee representatives were based in different offices.

- It potentially reduced opportunity for confrontation – some employers said online delivery reduced opportunities for aggressive behaviours and grandstanding and could be beneficial for some disputes where tensions are already high. One employer said:

"Some of them like to do drama and bang on tables … but it's less effective when you're at home on Zoom, isn't it?!" (E10, private sector, 2,000+ employees, repeat customer).

These findings confirm that it remains important for conciliators to ensure that hybrid delivery is offered to customers where appropriate.

2.3 What are customers' perceptions of conciliators?

Section summary:

- Customers' perception of conciliators was generally very positive, but employee representatives were more likely than employers to view their conciliators positively.

- Where views on conciliators were less positive, this was in relation to their knowledge of specific sectors, and their ability to contribute new ideas and solutions.

The findings in this section relate to the customers' views and experiences with conciliators. As shown in Figure 5, these findings align with a causal pathway in the Theory of Change: positive customer experiences with conciliators enhance Acas's reputation as experts in dispute resolution which, in turn, increases the likelihood that customers will seek Acas's services in the future.

Most customers rated their conciliator overall as 4 or 5 out of 5 (89%), on a scale where 5 is "very good" and 1 is "very poor". The average score across all customers was 4.5. Employee representatives were more likely to rate their conciliator as 5 out of 5: 78% of employee representatives felt this way compared with 49% of employers; and only 2% of employee representatives rated their conciliator a 3 or lower compared with 20% of employers.

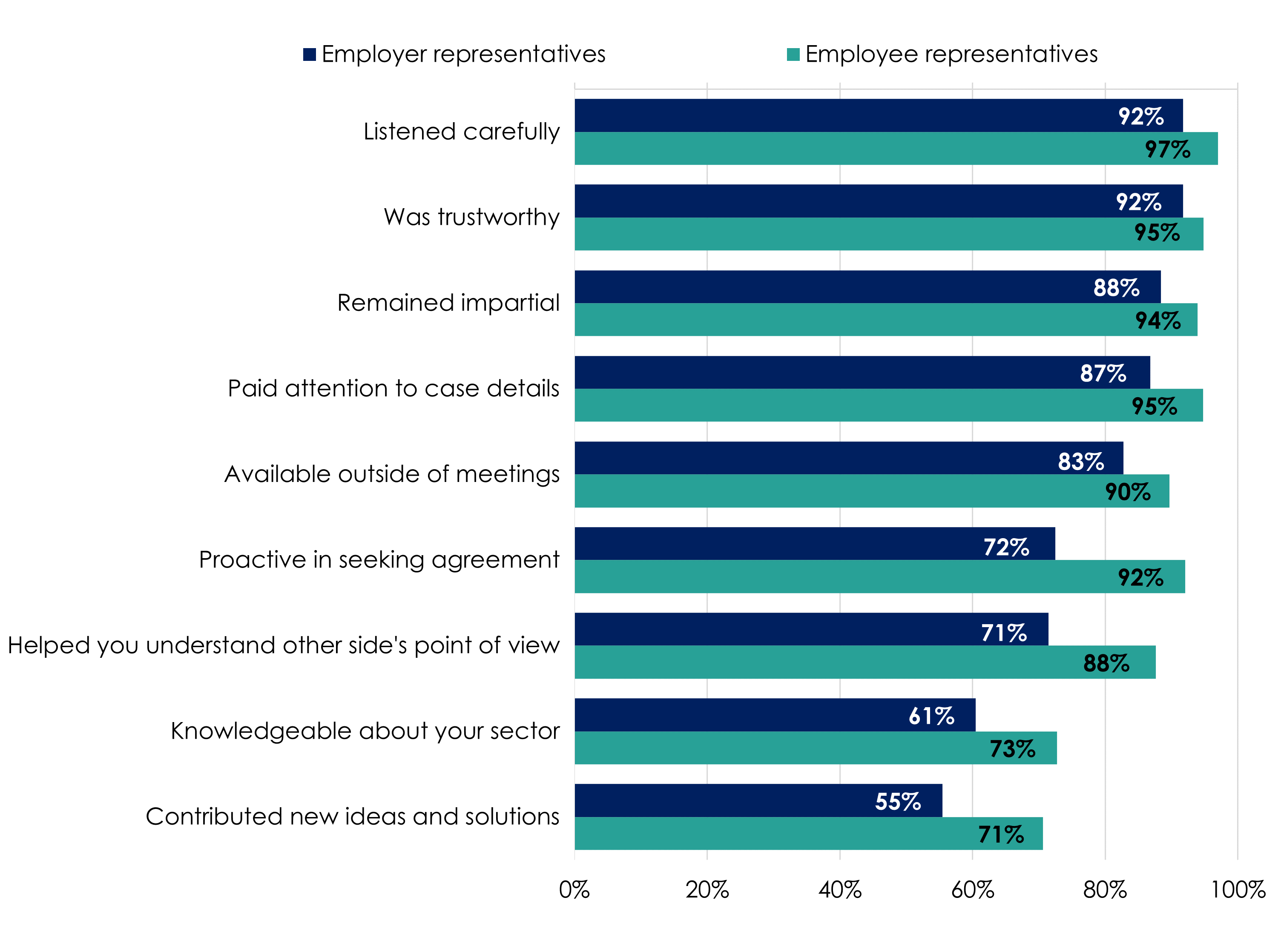

The vast majority felt that conciliators listened carefully, were trustworthy, and were impartial, among other attributes (Figure 6).

It was not possible to make comparisons between customer perceptions of conciliator attributes from the new 2022 to 2023 and previous 2014 to 2015 evaluation. This is due to differences in question wording as well as in the statements about conciliator attributes shown to the survey participants.

In qualitative interviews, impartiality and trustworthiness were considered especially important for building rapport and encouraging both parties to open up to the conciliator in confidence.

Smaller majorities felt that conciliators were knowledgeable about their industry or sector, or that the conciliator contributed new ideas and solutions. However, in qualitative interviews, there was some disagreement on whether sector knowledge was essential for a conciliator, or whether it was more important for them to show adaptability and add value to the negotiations.

Among both employers and employee representatives there was a view that disputes, and especially wage disputes, were similar enough across employment sectors that specific knowledge of the employer was not always necessary. For instance, one employee representative said that a "dispute is a dispute", and that it was more important that the conciliator understands where each party was coming from.

The main exception to this pattern was for complex technical industries, or in academia because of the highly qualified and subject-specialist nature of the workforce. Here, while sector knowledge was not essential to reaching a resolution, the process overall could be slower without it.

Base: All customers (237). The legend is presented in the same order as the categories within the bars.

| Conciliator attributes | Employer representatives | Employee representatives |

|---|---|---|

| Listened carefully | 92% | 97% |

| Was trustworthy | 92% | 95% |

| Remained impartial | 88% | 94% |

| Paid attention to case details | 87% | 95% |

| Available outside of meetings | 83% | 90% |

| Proactive in seeking agreement | 72% | 92% |

| Helped you understand other side's point of view | 71% | 88% |

| Knowledgeable about your sector | 61% | 73% |

| Contributed new ideas and solutions | 55% | 71% |

Although the survey found that most customers were broadly positive about their experience of the conciliator, the qualitative interviews shed light on the areas where customers were dissatisfied.

Three areas of dissatisfaction with conciliators were raised.

The need to add value to the discussions

Customers agreed that effective conciliators need to be able to reframe, rather than just repeat, information put forward by each side, to the other. This was to enable discussions to move forwards, through conciliators offering new ways of thinking about the dispute, and new ways to resolve it.

When this was not the case, employers felt that the conciliator was acting more as a messenger than contributing to the negotiations:

Perceptions of partiality

Employers sometimes felt that the conciliator was "siding" with a union, especially where the employee representative and conciliator had a pre-existing relationship. They said it sometimes felt like the conciliator was spending more time with the representative than them, and that they were acting more like colleagues. One employer said:

This reduced the level of trust employers had in the conciliator, making them feel less comfortable sharing information.

This finding should be read in the context of the survey finding, described above, that 88% of employers agreed that the conciliator had remained impartial, suggesting that such perceptions of partiality are in the minority.

Lack of professionalism and responsiveness

A lack of professionalism was reported as including inflexibility with availability, or conciliators not familiarising themselves with the parties involved in the dispute before the session.

Once again, it is important to contextualise this finding in association with the survey findings, which showed that large majorities of customers agree that the most conciliators exhibited professionalism. This included listening carefully, being available outside meetings, and paying close attention. Such perceptions of unprofessionalism were therefore in the minority.

Customers also said conciliators needed to remain consistently professional and personable, as small issues could cause customers to lose trust and favour quickly.

3. What are the outcomes and impacts of the collective conciliation service?

This chapter explores the outcomes and impacts of the collective conciliation service by looking at levels of customer satisfaction, the outcomes of disputes (both short and long-term), and whether the service led to any ongoing improvements in employment relations or organisational performance.

3.1 How satisfied are customers with the collective conciliation service?

Section summary:

- Customer satisfaction with the service has remained high.

- Employee representatives were more satisfied with the service than employers.

- Most customers would use the service again if they needed it.

Satisfaction with the Acas collective conciliation service

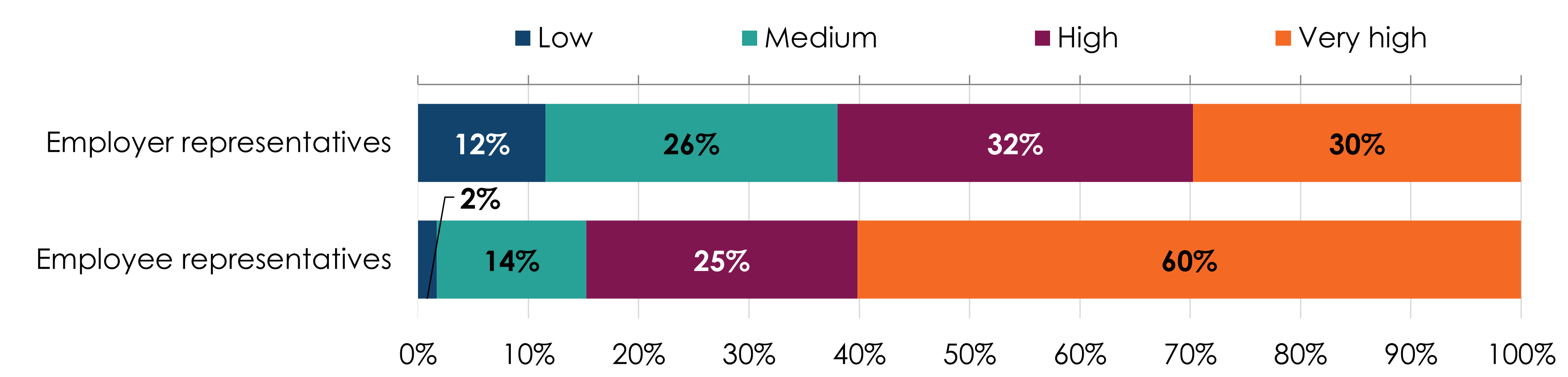

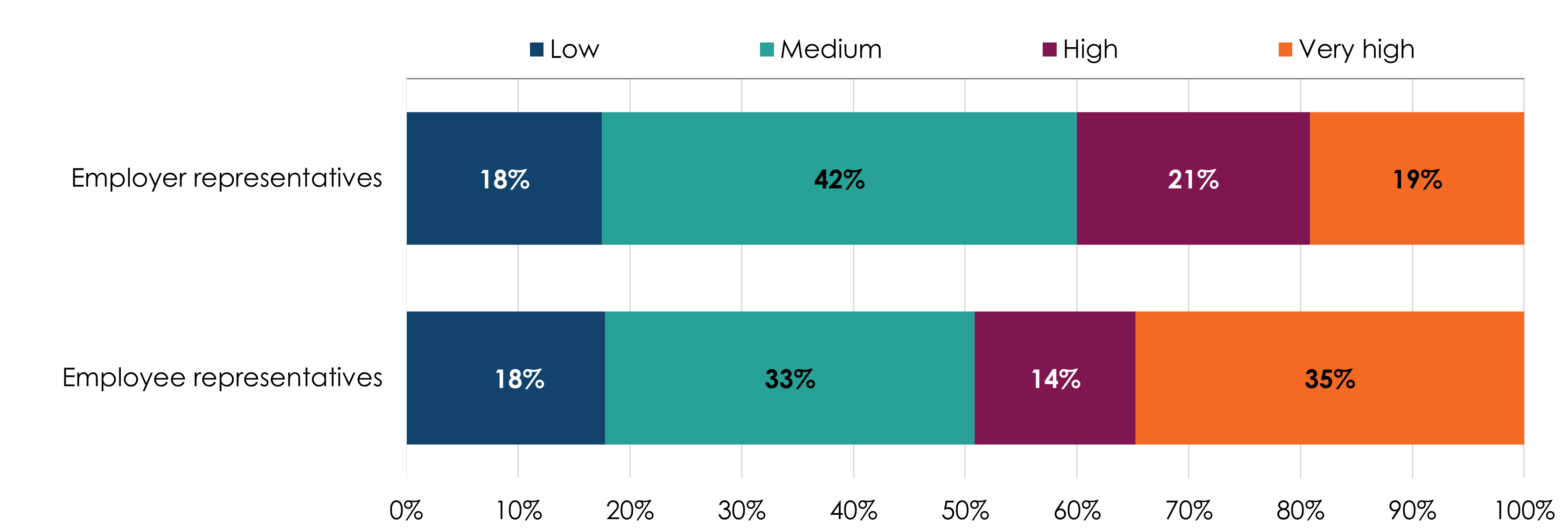

Overall satisfaction with the service was high: 73% of customers were highly satisfied with the service, rating it 6 or 7 out of 7 (Figure 7). These figures were similar in 2014 to 2015.

Base: All customers (239). The legend is presented in the same order as the categories within the bars.

The rating scale to explore satisfaction levels categorises scores from 1 to 7 into four levels: Low (1 to 3), Medium (4 to 5), High (6), and Very High (7).

| Overall satisfaction | Employer representative | Employee representative |

|---|---|---|

| Very high | 30% | 60% |

| High | 32% | 25% |

| Medium | 26% | 14% |

| Low | 12% | 2% |

However, some customers were more satisfied with the service than others. Employee representatives were twice as likely to rate the service a 7 out of 7 compared with employers (60%, compared to 30%), which is consistent with the difference in views on conciliators themselves, as reported in the previous chapter. Repeat users were more likely to be highly satisfied compared with first-time users (77%, compared to 65%).

However, this difference is entirely explained by the fact that most repeat users were employee representatives: there was no difference between repeat users and first-time users when looking only at employers or looking only at employee representatives.

Unsurprisingly, customers whose dispute was settled were more satisfied with the service. When all or most of the key issues in a dispute were settled, 82% of customers were highly satisfied (6 or 7 out of 7), but when no agreement was reached and no progress was made in a dispute, only 49% of customers were highly satisfied.

Qualitative interviews confirmed that the outcome of the dispute was the most important factor linked with customer satisfaction. Other key factors included how long it took to achieve the outcome, and the extent to which conciliators were able to move parties towards understanding each other's positions and willingness to compromise. We discuss these factors further in section 3.2.1.

Likelihood of using Acas collective conciliation in another dispute

Acas has an ambition for effective delivery to lead to greater appetite to use Acas services in the future. As shown in Figure 8, this aligns with a causal pathway in the Theory of Change: as Acas's reputation as experts in dispute resolution strengthens, so does the appetite for using its services in the future.

Almost all customers said they would be likely to use collective conciliation in the future if they were involved in another employment dispute (89%), with most being very likely (62%) to re-use the service. This was unchanged from 2014 to 2015.

Around 1 in 10 customers would be unlikely, or neither likely nor unlikely, to use the service again in the future (11%). Reasons given for being unlikely to use the service again included:

- concerns around impartiality or that there would be no real benefit to using the service

- the service could prolong the process

- conciliators sometimes had basic advice

- the other party is unlikely to move

- no progress in the previous dispute was made

These factors were also reflected in the qualitative interviews, although the perceived intransigence of the other party, and a lack of sufficient preparatory work by conciliators and the parties to enable compromise, featured strongly in the interview accounts.

3.2 To what extent does collective conciliation help to resolve disputes?

Section summary:

- In most cases, disputes were either settled or progress was made, and Acas was seen as having played an important role in achieving this.

- In most settled cases, both parties compromised to some extent, and were generally satisfied with the outcome.

- However, there was a slight drop in the proportion of cases that customers felt were resolved in the long term. Again, this may relate to the increase in pay-related disputes, which can recur on an annual basis.

- Customers were typically less satisfied with the outcome of pay disputes than other kinds of dispute.

3.2.1. What are the short-term outcomes of collective conciliation?

The findings in this subsection relate to the outcomes of disputes and whether industrial action was avoided. As shown in Figure 9, 4 short-term outcomes in the Theory of Change are generated by 4 key outputs:

- where agreement is reached, a draft written agreement is produced, which the trade union then uses to ballot its members – this ballot can result in the resolution or improvement of the employment dispute, for example the acceptance of a pay offer

- where no agreement is reached, action points are generated for the parties to consider, along with Terms of Reference if the case proceeds to arbitration or mediation – this can lead to the referral of the case to arbitration or mediation

- the other 2 short-term outcomes at this stage are the pausing, stoppage, or avoidance of industrial action and the reduction of differences between the parties

Outcomes of disputes

In 2022 to 2023, three-quarters of customers judged the dispute as having been settled or progressed:

- over half felt the key issues in the dispute were settled (58%)

- 16% felt some progress was made

- 1% of disputes went on to arbitration

This was unchanged from 2014 to 2015. Note that the settlement rate was no lower for pay disputes than for other kinds of disputes. However, it should be noted that customers and conciliators do not always agree on the outcome of a case.

We can compare how conciliators themselves classified the outcome of a dispute with how customers classified it. In most disputes (80%), conciliators had classified the outcome as settled. Of just these disputes, customers felt that all or most of the key issues in the dispute were settled in 67% of cases and that some progress was made or the case went to arbitration in a further 17% of cases. According to customers, no agreement was reached and no progress was made in 10% of these cases.

In cases where a settlement was agreed during conciliation, almost half of customers said this had involved a little movement from the initial position (48%). In almost a third, they judged that the settlement involved a moderate movement (29%). This was also consistent with 2014 to 2015 figures. This is a positive finding given that the 2022 to 2023 evaluation included a higher proportion of pay disputes; qualitative interviews found that the parties' starting positions were far apart in these cases. More information on the state of disputes when Acas became involved is discussed in section 2.1.2.

In qualitative interviews, customers explained that conciliators helped to reach agreements by encouraging both parties to look at alternative ways to resolve their annual pay review, beyond the ones they were used to. For example, in one case, this included a second, interim review point in the year for salary increases should the employer's financial position improve. The conciliatory tone of the conciliator also helped move them past an impasse:

Despite this, a fifth of customers (19%) said that no agreement was reached. In general, customers felt this was because the gap between the parties was too great: 34% gave this exact reason, while 37% felt the management side would not shift position, and 25% felt the employee side would not shift position. This view was also found in the qualitative interviews, with difficulties in negotiations being reflected in the level of satisfaction with Acas conciliation and its outcome. In 2014 to 2015, a matched-case analysis showed that the 2 parties can sometimes hold different perspectives on case outcomes. This evaluation was not able to focus on matched cases to explore any differences in responses due to a smaller sample size.

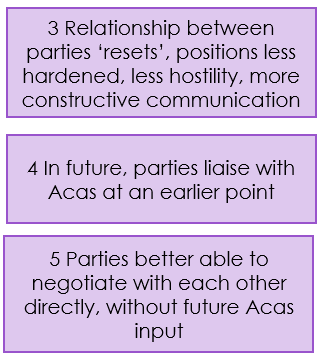

Satisfaction with case outcome

In addition to their satisfaction with the conciliator and with the service, customers were asked about their satisfaction with the outcome of the case. Almost half of customers were highly satisfied with the outcome of the dispute (45%), rating it a 6 or 7 out of 7. 43% of customers gave a medium-rating for their satisfaction with the outcome (3, 4 or 5 out of 7), and just 13% rated their satisfaction as low (1 or 2 out of 7). These figures are unchanged from 2014 to 2015. Employee representatives were more likely to rate the outcome of the dispute with the highest level of satisfaction (a 7 out of 7) compared with employers (35% compared to 19%) (Figure 10).

Base: All customers (238). The legend is presented in the same order as the categories within the bars.

The rating scale to explore satisfaction levels categorises scores from 1 to 7 into four levels: Low (1 to 3), Medium (4 to 5), High (6), and Very High (7).

| Satisfaction levels | Employer representatives | Employee representatives |

|---|---|---|

| Very high | 19% | 35% |

| High | 21% | 14% |

| Medium | 42% | 33% |

| Low | 18% | 18% |

Customers who experienced a dispute about pay were less likely to be satisfied with the outcome: customers were around half as likely to rate their satisfaction with the outcome as 7 out of 7 when the dispute was about pay (22%) compared with customers whose dispute was not pay-related (41%).

From the qualitative interviews, customers who were most satisfied with the outcome of conciliation had avoided industrial action, settled a dispute, or experienced improvements in workplace relations between the employer and employee representatives (including sometimes achieving a union recognition agreement).

Customers described positive short and medium-term outcomes in 2 ways:

- As concrete, lasting changes – such as a 3 year pay deal, improved pensions provisions, or a union recognition agreement.

- The avoidance of industrial action – thereby facilitating better workplace relationships. This included re-stabilising previously good relationships or forming new, better workplace relationships.

Medium levels of satisfaction reflected that progress was eventually made in disputes, but sometimes took months to negotiate and settle, or that a settlement was only reached immediately prior to a group claim being heard by an employment tribunal, or after industrial action.

Customers expressed lowest levels of satisfaction with case outcomes where employers and employee representatives felt that one or both parties had entered the conciliation with entrenched positions. In some cases, the way in which a dispute was resolved in the short-term could lead to resentment in the longer-term:

3.2.2. What are the medium-to-long term outcomes of collective conciliation?

Section summary:

- In most cases where an agreement was reached and implemented at least in part, this resolved the dispute in the long term.

- However, in 2022 to 2023, disputes were slightly less likely to be seen as resolved in the long-term compared to 2014 to 2015.

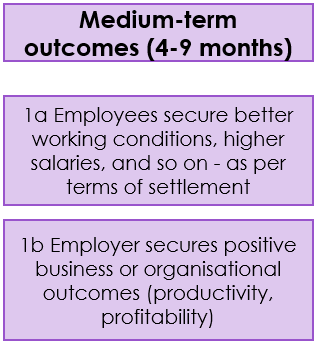

The findings in this subsection relate to the medium-term outcomes of collective conciliation that arise from the implementation of agreements, as shown in Figure 11:

- employees may secure better working conditions, higher salaries, and other benefits as outlined in the terms of a settlement

- employers may achieve positive organisational outcomes, such as enhanced productivity and profitability

The vast majority of settlement agreements were implemented in full (90%). A minority were implemented in part (5%) or were not implemented (5%). This was unchanged from 2014 to 2015.

In 2022 to 2023, disputes were slightly less likely to be resolved in the long term. Of those cases in which a settlement was reached and the agreement was implemented (at least in part), 67% of customers felt the dispute was resolved in the long term in 2022 to 2023, compared to 77% in 2014 to 2015. Overall, across all disputes, this means that in 2022 to 2023, 36% of customers said the dispute was resolved in the long term by an agreement reached during conciliation.

This slight fall in the number of disputes that are resolved in the long-term may be associated with the increase in pay-related disputes, since these can be likely to reoccur. As one customer put it:

15% of customers reported that industrial action took place after Acas involvement.

It was not possible to make comparisons between the prevalence of industrial action taking place after Acas involvement from the new 2022 to 2023 and previous 2014 to 2015 evaluation. This is due to differences in questionnaire routing, meaning which customers were shown the question.

However, even though some employers and representatives reported that industrial action was taken after conciliation, this did not necessarily mean that the service had not had any positive effect. Employers in the qualitative interviews gave examples where employee representatives would sometimes return to a compromise suggested previously at conciliation when it was clear industrial action was not having any effect. However, others described industrial action as having arisen from the perceived intransigence or immovability by one or either party.

3.2.3. What role does Acas have in achieving positive outcomes?

Section summary:

- Overall, Acas has an important role to play in achieving positive outcomes.

- Where disputes were resolved, customers felt Acas was an important factor, and in disputes that were not resolved, most customers felt Acas could not have done more.

What did Acas do to help achieve positive outcomes?

Among customers whose dispute was resolved, most judged that Acas's involvement had been important: 87% rated conciliation as having been quite or very important in bringing about a resolution. This was consistent across customer groups.

For the large majority (85%) of customers involved in disputes where industrial action did not follow conciliation, most (60%) credited Acas as having been either very important (31%), or quite important (29%) in avoiding industrial action, whereas 19% felt the conciliation had not been very important (11%), or not at all important (8%), and 21% judged that there had never been a risk of industrial action to start with.

In qualitative interviews, employers and employee representatives said there were 2 main ways in which conciliation made a positive difference.

Assisting in understanding the position of the other party and reducing resentment

Conciliation helped each party understand the 'logic and reasoning' of the other party’s demands, thereby helping to reduce feelings of resentment that may underlie their positions:

Positively influencing negotiation behaviour by being a positive, independent, and neutral observer

Both employers and employee representatives said that having a conciliator present helped formalise the process in a way that meant that bad behaviour and being unreasonable during negotiations were regarded as less acceptable.

What more could Acas do to achieve positive outcomes?

In disputes that were not resolved, most customers (95%) felt that the conciliator could not have done any more to bring about a settlement. This was because one or both parties were seen as being intransigent in negotiations, or because going to conciliation was a procedural commitment rather than a genuine attempt at negotiation and compromise.

In qualitative interviews, customers felt that conciliation worked best where both parties went into it understanding that they may have to compromise or consider alternative options to achieve a positive outcome. Related to this, they also felt that success depended on how engaged one or both parties were in the process. Both employer and employee representatives said that, in order to exhaust all possibility of the dispute resulting in industrial action or a group claim being heard by an employment tribunal, conciliation needed to be more than just a tick box exercise or an obligatory procedural step.

Successful conciliation required the parties to be prepared to consider new positions or options, and talks should not simply be a repetition of existing arguments, simply involving Acas as a third-party onlooker.

Where customers thought that conciliators could have done more, this primarily related to ensuring that both parties entered the process understanding that they would need to compromise and to fully engage. Employee representatives emphasised their experience of cases where they felt the conciliator had probably moved towards holding formal conciliation talks too quickly, without exploring possible areas of compromise between the parties in advance:

Another employee representative said:

As above, where parties believed the other party was intransigent going into the conciliation process, this could lead to a worsening of employment relations rather than an improvement.

3.3 Does Acas collective conciliation improve employment relations?

Section summary:

- In general, conciliation tended to bring sides closer together on the dispute at hand.

- However, it only led to substantial ongoing improvements in employment relations in a minority of cases.

This section looks at whether collective conciliation improved employment relations in the medium-term. As shown in Figure 12, these findings correspond to 3 medium-term outcomes in the Theory of Change:

- the relationship between parties resets, becoming less hostile and more constructive

- the parties engage with Acas earlier in future discussions

- they are better able to negotiate with each other in the future, without needing Acas's input

More than half of all customers agreed that Acas had brought the sides closer together on the key issues of the dispute (56%). This was unchanged from 2014 to 2015 and was consistent between pay disputes and other kinds of disputes. Employee representatives were more likely than employers to agree that Acas had brought sides together (65% compared to 47%).

Around half of customers felt that conciliation had helped to improve employment relations within the organisation (48%). Those who felt the service had helped to improve employment relations were much more likely to indicate that they were highly satisfied with the service, compared to those who did not feel this way (67% compared to 27%).

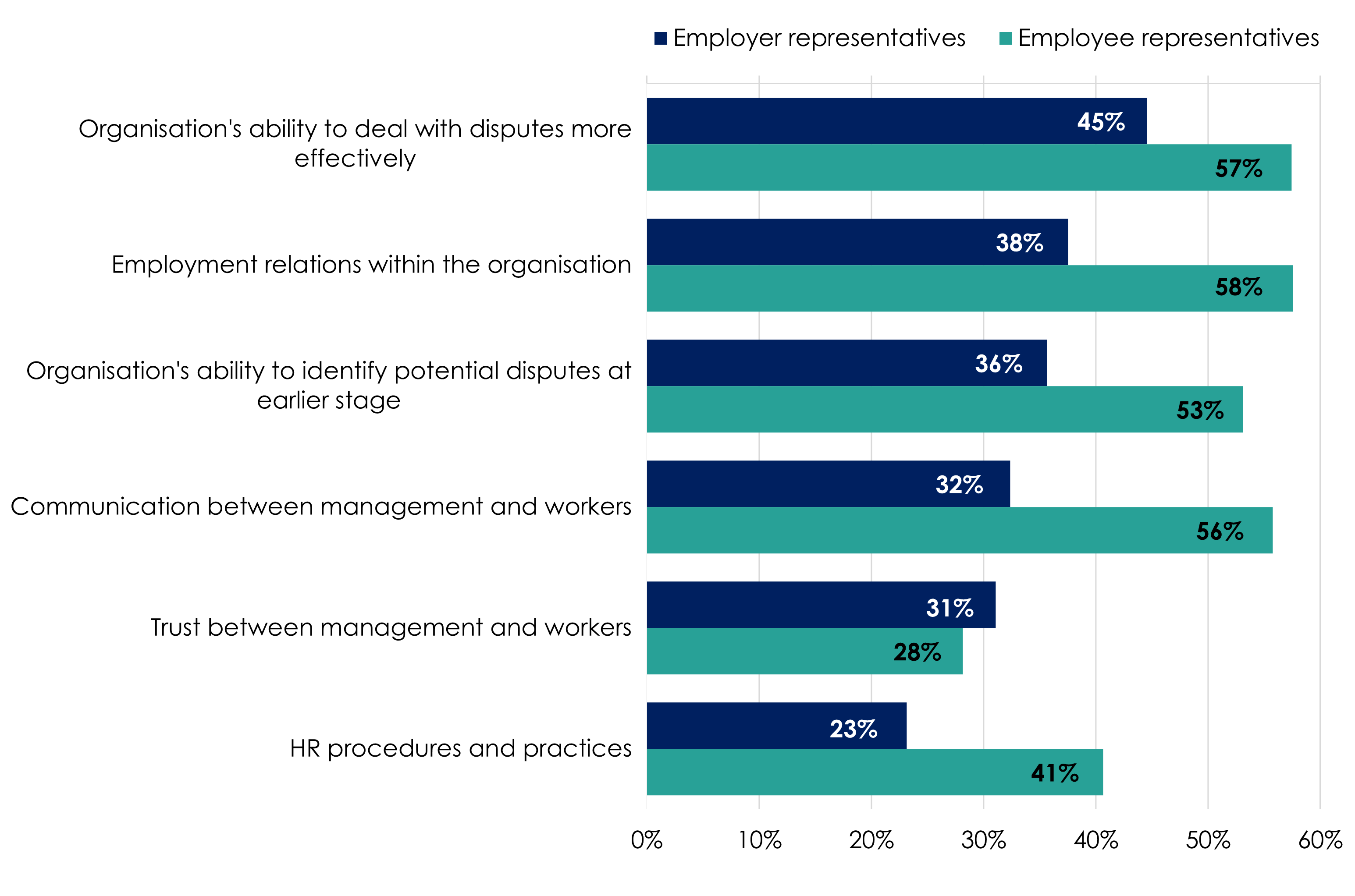

A range of other improvements to specific aspects of employment relations were reported (Figure 13). In general, employee representatives were more likely than employers to feel that conciliation had led to these ongoing improvements.

Base: All customers (241). The legend is presented in the same order as the categories within the bars.

| Improvements | Employer representatives | Employee representatives |

|---|---|---|

| Organisation's ability to deal with disputes more effectively | 45% | 57% |

| Employment relations within the organisation | 38% | 58% |

| Organisation's ability to identify potential disputes at earlier stage | 36% | 53% |

| Communication between management and workers | 32% | 56% |

| Trust between management and workers | 31% | 28% |

| HR procedures and practices | 23% | 41% |

Over time, building good workplace relationships on the back of conciliation also helped to set up ways of working to prevent future disputes emerging or escalating. This included establishing management-employee working groups on specific issues.

It also included establishing lines of communication, and sometimes, in large organisations, establishing a union representative working full-time with HR representatives to deal with problems earlier before they arose. For example:

Employers and employee representatives said that they had learned new behaviours and skills from the conciliation process. They discussed 3 types of learning.

Being better prepared for conciliation

Customers said they now thought more carefully about whether they were at the right point to involve Acas in disputes. This included making sure preliminary conversations had taken place, and ensuring there was some 'room for manoeuvre'.

In perhaps a less positive way, one employer said they now made sure they checked the legality of their position so they could not be 'tripped up'.

Learning from the behaviour of the conciliator

This included emulating behaviours like remaining calm during negotiations and being more conciliatory and less adversarial in style.

Adopting the style of conciliation to create more meaningful dialogue in disputes, sometimes preventing the need for conciliation

Sometimes, the learning discussed above made employer and employee representatives consider whether they could emulate aspects of conciliation as part of their own approach to dispute talks, so that there would be less of a need to involve Acas in future disputes.

3.4 Does collective conciliation support long-term organisational improvement?

Section summary:

- Up to a third of customers said that conciliation had brought about improvements in staff morale and the organisation’s ability to deal with change – but few felt that conciliation had led to other forms of organisational change.

- Around half of all customers said that the conciliator had contacted them after conciliation had been completed.

- Some customers who did not receive any follow-up contact would have liked to have received it.

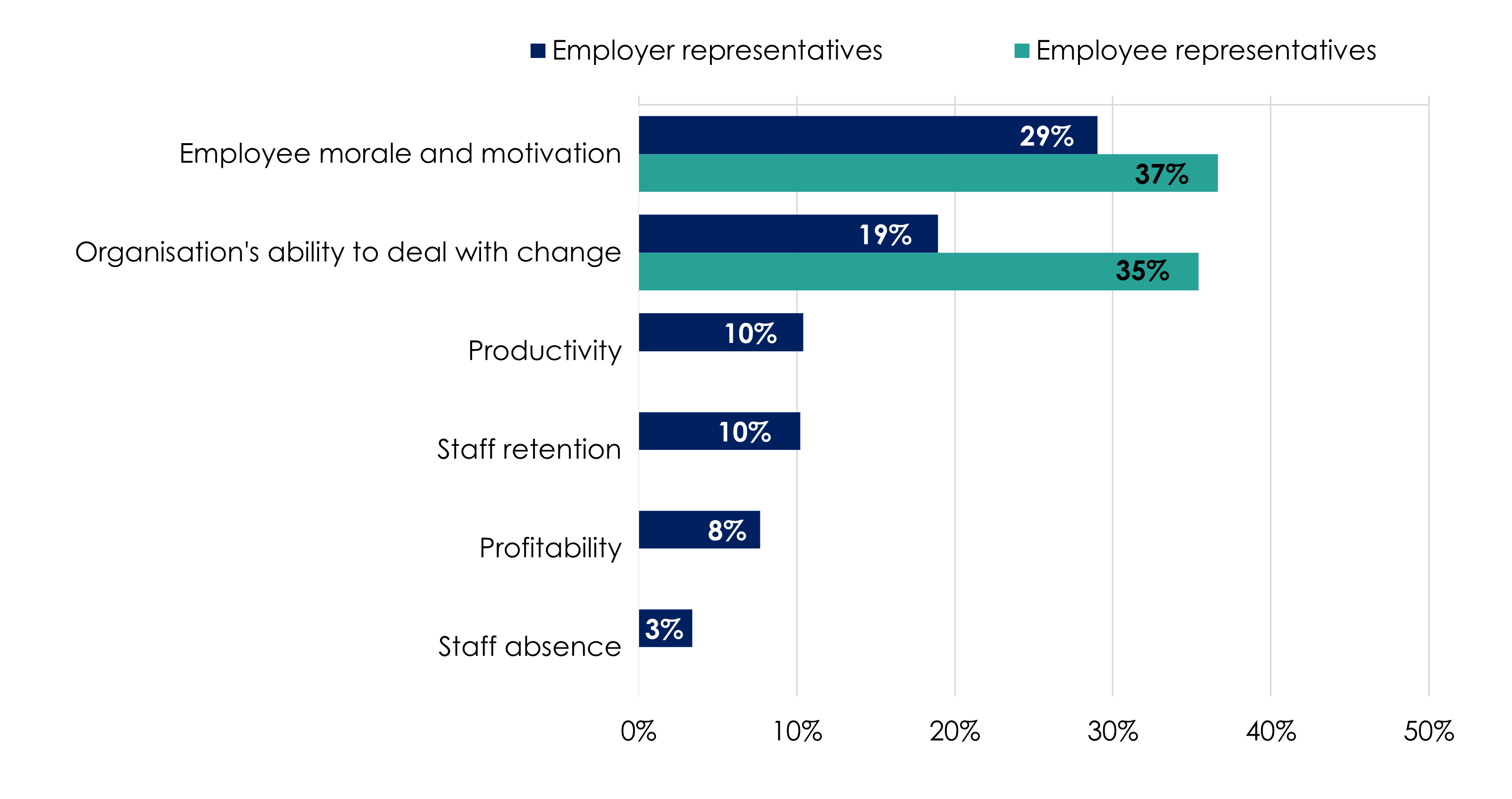

The survey also asked about various organisational impacts beyond the immediate scope of what conciliation seeks to achieve. In general, collective conciliation had led to these ongoing positive changes in a minority of cases.

3.4.1. Does collective conciliation effect organisational change?

Around a third or fewer customers felt that conciliation had led to improvements in the organisation's ability to deal with change, or improved employee morale and motivation. Very few employers felt that conciliation had led to improvements in productivity, staff retention, profitability, or staff absence (Figure 14).

Employee representatives generally felt more positive about these outcomes than employers. Customers who felt conciliation had led to these positive changes also tended to be more satisfied with the service as a whole.

Base: All customers (241). The legend is presented in the same order as the categories within the bars.

| Organisational impacts | Employer representatives | Employee representatives |

|---|---|---|

| Employee morale and motivation | 29% | 37% |

| Organisation's ability to deal with change | 19% | 35% |

| Productivity | 10% | not applicable |

| Staff retention | 10% | not applicable |

| Profitability | 8% | not applicable |

| Staff absence | 3% | not applicable |

3.4.2. Does Acas offer and deliver follow-up work after cases end?

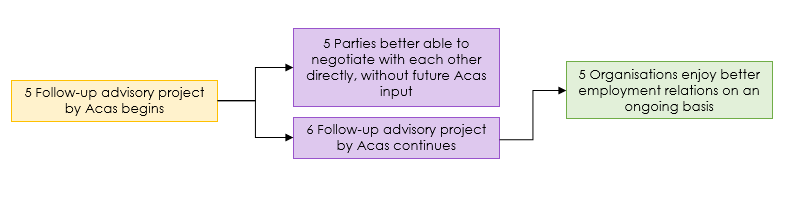

The findings in this subsection relate to whether customers are being offered and receive Acas follow-up work. As shown in Figure 15, these findings align with a causal pathway in the Theory of Change:

- the initiation of a follow-up Acas advisory project enhances the parties' ability to negotiate directly with each other in the future

- subsequently, the continuation of the advisory project contributes to organisations experiencing improved ongoing employment relations

Customers were split evenly between those who were contacted by the conciliator to check on progress after the case had finished (46%), and those who received no such contact (50%). Employee representatives were more likely to have been contacted than employers (58% compared to 34%).

Of those customers who were not contacted by the conciliator to check how things were going after the case finished, 1 in 5 said they would have found this useful (21%). This means that overall, 10% of all customers were not contacted and would have found it useful. In qualitative interviews, these cases tended to involve situations in which the relationship between parties was persistently bad, and where these customers thought Acas could help them to build relationships of trust and mutual respect going forward. Customers who did not think they would have found follow-up contact useful tended to see the agreement as the end of the process:

Additional follow-up work was only carried out by Acas in around 1 in 10 cases (13%). Employee representatives were more likely than employers to say that follow-up work had been carried out (17% compared to 10%). In qualitative interviews, follow-up work was of 2 kinds.

The first kind was a simple follow-up, where the conciliator helped write-up notes on the case or the agreement and checked that both parties were doing well sometime after the dispute.

The second involved more proactive work as part of a project delivered by Acas: offering training to support building trust or mediation skills; helping to improve how issues were presented to staff and their representatives; helping to develop new working arrangements; or establishing regular meetings between the parties.

These regular meetings were particularly well received. One employer described how it made them feel that the Acas conciliator was part of their journey towards better workplace relationships.

A particularly well-received example of follow-up work was where the conciliator organised a workshop with managers and representatives to talk through their respective roles, and to have honest conversations about working together. The employer said:

4. Discussion: lessons for future service development

Acas's collective conciliation service remains a core part of Great Britain's employment relations infrastructure. It is overwhelmingly positively received by its customers. Much more often than not, disputes that go through the collective conciliation process achieve positive outcomes.

Like other public services, collective conciliation has had to contend with a range of unique challenges over recent years. The covid pandemic led to the single biggest change in the delivery of the service in decades, shifting from entirely face-to-face to wholly online. Since then, the service has continued to operate using a hybrid model, and in 2022 to 2023, 30% of disputes were conciliated at least partially online or by phone. While most customers valued face-to-face contact, they also valued being given the choice of face-to-face, online or hybrid conciliation.

Alongside this, the sharp increase in the cost of living since 2021 has led to more difficult-to-resolve pay disputes reaching Acas, as unions seek larger annual increases, while employers continue to grapple with the fallout of the pandemic. Three-quarters of disputes in 2022 to 2023 (74%) were about pay, compared to under half (46%) of disputes in 2014 to 2015. In qualitative interviews, customers described being far apart in their initial positions, leading to disputes escalating quickly and a sense of urgency from both sides to resolve disputes as soon as possible. Most recently, Britain has seen a wave of high-profile industrial action across the public sector: in 2022 to 2023, 63% of disputes coming to Acas had already involved industrial action, a ballot on it, or the threat of it, compared to just 48% in 2014 to 2015.

The evidence shows that the service has generally weathered this well. Three-quarters of 2022 to 2023 disputes were judged by customers to have been settled or progressed – key issues were settled in 58% of disputes, in 16% progress was made, 1% went on to arbitration – which is unchanged since 2014 to 2015. 73% of customers were highly satisfied with the service, rating it 6 or 7 out of 7, 89% would use the service again if they needed to, and the same proportion gave their conciliator a 4 or 5 out of 5 rating. Again, these figures are unchanged from 2014 to 2015.