Disclaimer

This is an evidence-based research paper prepared for Acas by Dr Emma Russell of the Wellbeing at Work (WWK) Research Group at Kingston Business School, Kingston University.

The views in this research paper are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the author alone.

For any further information on this study, or other aspects of the Acas research programme, email research@acas.org.uk

1. Executive summary

Electronic mail – or email – has been a central feature of working life for well over 20 years. Originally conceived as a means for communicating in a text-based format, its use has evolved to its current state as an essential tool for managing, scheduling, communicating and co-ordinating seemingly boundary-less elements of work today. Often maligned in the popular press as enslaving workers by the tyrannical control it apparently exerts (MailOnline, 2016; Burn-Calder, 2014), email nevertheless retains its popularity as the most commonly used work communication method. As such, in this research project we sought to understand how email might help people to achieve their work goals, and the strategies that are adopted by workers to differentially impact both wellbeing and productivity.

In undertaking this programme of research, our primary aim was to identify factors (or themes) that explain the strategies used to deal with work email. This helps us to understand how, why, when and for whom such strategies will have positive and negative repercussions on productivity and wellbeing outcomes. To achieve this aim we designed 2 research phases.

In phase 1, we conducted a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) to provide a rigorous and transparent review of the academic and practitioner research that has been conducted across psychology, management and human-computer interaction fields. From this we extracted three key themes (and 10 sub themes) relating to the effectiveness of workers' strategies for dealing with work email. In phase 2, we held semi-structured, sense checking interviews with 12 working adults. These sense checking interviews validated the interrelated themes identified at phase one, and provided further illustrations of workers' strategic use of work email.

The 3 key themes identified in our research suggest that strategies for dealing with email relate to:

1. Culture – a culture of use has developed within and beyond organisations that both influences and is influenced by the second element.

2. Adaptation to email use and development – workers have developed email behaviours over time that have both positive and negative implications for different goals.

3. Individual differences in email experience – our subjective perceptions and experiences of email depend in part on our personality, job role and demographics, and in part on our perceptions of email as a stressor. Person-led responding impacts not only the strategies we use, but also the outcomes from using these strategies.

We précised our findings from both research phases by providing summary tables of the specific strategies found to be positively and negatively related to productivity and wellbeing outcomes across different groups. This provides a shortcut to differentiating which email strategies are currently working for people.

These strategies are associated with:

- enhanced work productivity – includes utilising automated/shortcut strategies (often developed through experience and standardisation)

- reduced work productivity – includes reactive emailing (usually resulting from a pressure to respond quickly to incoming messages)

- enhanced wellbeing – includes actively embedding email into one's normal working day

- reduced wellbeing – includes addictive checking of email, often via devices

In carrying out this rigorous review of the literature, along with the sense checking interviews, it was interesting to find that a number of popular conceptions about email are questioned by our findings. Some of the 'myths' that this report appears to bust include:

Email is stopping us from fostering high-quality work relationships.

Research-led Mythbuster:

Email only reflects and potentially accentuates existing cultures of trust.

What the research says:

If the culture of trust is already poor then email use simply reflects this – for example, email users will keep 'back-covering' audit trails of communications, regularly misinterpret email content, display poor email etiquette, and use 'cc' to hold others accountable. When the existing culture of trust is good, email is used to forge new and rewarding relationships, keeps people informed (such as through 'cc'), and allows people to be considerate about others' time pressures.

Myth No. 2:

We should limit ourselves to checking email a few times a day.

Research-led Mythbuster:

We need to check and process email regularly in order to prioritise and control our work effectively.

What the research says:

Although allowing ourselves to continuously be interrupted by email has been shown to negatively impact productivity, limiting access to it also has negative implications, namely because of the build up of tasks in the inbox. By turning off email alerts and allocating time to check and deal with it at regular intervals, research reports that people feel more in control and less overloaded by email.

Myth No. 3:

Email is a time-wasting distraction from 'real' work.

Research-led Mythbuster:

A tiny proportion of email sent and received at work is non-work critical.

What the research says:

People use email to help them get their jobs done more efficiently, with most people reporting that email is now an essential work tool for them. Very few people engage in non-work critical email during their working day. With a few exceptions, email is now embedded into people's daily work activities, and email users report that they would struggle to get their work done effectively without it.

These sorts of findings serve to remind us of the importance of developing research-led recommendations, or learning points, to translate study results into work practice. In this report, evidence-based learning points are provided for managers, organisations and individuals. These learning points suggest that individuals and organisations can improve email strategies by:

Individuals

1. Processing and clearing email whenever it is checked, can avoid inbox clutter that can make people feel overloaded

2. Switching off interrupting alerts but logging on regularly, can help to stay on top of email and new work priorities

3. Using the 'delay send' function so that the recipient isn’t disturbed, when sending email outside of the recipient's contact hours

4. Reviewing personal email strategies – are they purposeful and efficient or habitual and reactive? Can we use our email better?

Organisations

5. Developing 'email etiquette' guidance to facilitate a culture of trust

6. Removing response time recommendations for replying/dealing with work email messages

7. Putting contingencies in place to deal with high work email volumes – such as team inboxes, out-of-office expectation setting

8. Providing extra time-allocation in workloads for those with proportionately higher volumes (for example, managers and part-time workers)

9. Providing email training – in systems and strategies – and ensuring that managers model best practice

10. Considering other tools – are there better alternative systems available to help workers navigate modern work communication?

These learning points provide a useful starting point for practitioners wishing to develop a programme for optimising workers' email strategies, in order to positively impact outcomes. We also provide suggestions to researchers, based on our findings, as to how the research field may wish to focus its attention moving forwards. Continuing to develop understanding of the mechanisms and factors involved in people's strategic use of work email will ensure that workers can be advised on how best maximise effectiveness and protect wellbeing, as work-based email and new technology communications continue to evolve.

2. Introduction

In 1971, the first text-based message was sent via a computer from one user's electronic account to another's. When Ray Tomlinson introduced the '@' symbol in 1972, electronic mail – or email – was born (Leiner and others, 2009). More than 45 years later email has fully permeated working life, being used today as a tool not only to communicate and co-ordinate information, but to manage task lists, organise and store project knowledge, plan and schedule meetings and events, oversee multiple project strands, build relationships and enable flexible working (Clarke and Holdsworth, 2017; Dabbish and others, 2005; O'Kane and Hargie, 2011; Venolia and others, 2001). Its functionality has progressed well beyond what any designer could have originally expected, as the process of mutual shaping and development between technology, worker and work context has evolved the medium to the unrivalled system we see today.

Unrivalled, but not necessarily superior; whilst email affords a range of functions that allow workers to effectively attain their goals, a combination of poor worker strategies, pressurised work cultures and design limitations means that email also has the potential to impair workers' goals. To address these issues, the literature swells with an abundant supply of management self-help books and websites, and a growing army of consultants and email gurus are being employed to assist organisations in improving their email management. Within the academic field, research into the application and use of email systems across a range of field and laboratory settings has been designed, with results reported in psychology, management and human-computer interaction (HCI) domains. Studies and guidance into how we should best manage our email have therefore never been more plentiful, and yet organisations and end users are increasingly confused about which sources they should be using, and whose advice they should be taking.

2.1 Remit for this research project

The remit for this programme of research was therefore to provide Acas with an overview of the current state of empirical research into email-use and to outline validated findings from psychology, management and HCI research domains about: (i) when work email may cause problems for people, (ii) when work email has beneficial outcomes for people, (iii) whether there are particular groups that are more or less impacted by issues associated with work email, and, (iv) what strategies are associated with positive and negative outcomes, relating to how people deal with work email.

Our primary aim in this research programme was therefore to identify themes that would explain the emergence of work email strategies, which have positive and negative repercussions for productivity (including work performance and goal achievement) and wellbeing (including engagement and strain). We also aimed to provide evidence-based learning points about which strategies might be adopted by workers and organisations, to optimise the positive impact of work email, and reduce potentially negative outcomes.

2.2 Research context

Email enables workers to access (and be accessed by) work in a seamless, 24-hour-a-day stream, allowing for virtual working that transcends previous constraints such as time and location boundaries (Cascio, 1998). At the same time, these technological developments have impacted wellbeing and productivity, as people struggle to: (a) manage their work-life boundaries, (b) enjoy respite from work, and (c) cope with information overload (Derks and others, 2014; Golden and others, 2006). Alongside the ever-expanding research literature into the application of email at work, we are also seeing a movement at an organisational – and even a national – policy level to produce guidance and recommendations about how best to manage email. Many of the recent policy initiatives have especially focused upon restricting access to work email outside of working hours.

For example, in 2014 the German employment minister, Andrea Nahles, commissioned a report investigating the viability of legislation that would restrict the use of email outside work (The Guardian, 2014). It is already unlawful in Germany for employees to contact staff during holidays. Several major German companies such as Volkswagen, Daimler and BMW have implemented restrictions on contacting employees out of hours. In France, employers' federations and unions have signed a new, legally binding labour agreement that requires employers to ensure employees have 11 hours uninterrupted rest from work, by "disconnect[ing] communication tools" after they have worked a 13-hour day (The Economist, 2014). This came into French employment law on January 1st, 2017 (France-Presse, 2016).

In the UK we have not yet seen government-led policy or guidance limiting access to email in the workplace, but organisations have begun to develop their own policies. For example, Atos (a leading international IT solutions and digital innovations company) has banned internal emails, but replaced these with other ecommunications methods (such as instant messenger). Yet, focusing on replacing one communication technology with another could be a misplaced solution for organisations hoping to improve workers' effectiveness.

Attending to the technology, rather than the strategies for using the technology, means that problematic strategic behaviour (such as reactive responding, or lack of concision) could simply move from email to the new communication method, if email is replaced. Identifying the work email strategies that have problematic or beneficial outcomes for workers is thus an essential objective in educating organisations and society about how to manage and deal with communication technology as it continues to evolve - and the key aim of this research. A failure to attend to the themes impacting email-use, and how email use impacts the wellbeing and productivity of individuals and organisations, means that the UK's economy, health and wellbeing may fail to flourish optimally.

In this context, strategies are defined to be 'goal-directed actions'; effective resource deployment mechanisms that are under a worker’s control and chosen from other actions that are available to meet workers’ goals (principally relating to productivity and wellbeing). It is noted that many strategic behaviours become automated over time, with repeated exposure to similar events.

At such times, the original goal-achieving functions of the actions may become eroded. We seek to examine workers' different strategic responses to email, and the extent to which these are functional in terms of people's goals within and beyond the organisation, and across industry sectors. By examining the effectiveness of email strategies we hope to assist individuals and organisations in developing policies and recommendations to end users about how best to deal with email as technology develops and work contexts change.

2.3 The report

In this report, we present our research by briefly outlining the methodology used (Chapter 3, Methodology) to conduct the Systematic Literature review (SLR) and sense checking interviews. We then present our interpretation of the findings from the SLR (Chapters 4 to 7), grouped into 3 key themes that house 10 sub-themes. These themes formed the basis of our interview guide.

Findings in Chapters 4 to 7 are synthesised as a review of the key cross-discipline literature that was returned from the SLR, interspersed with findings from the sense checking interviews, to provide an integrated account.

In Chapter 8, we draw together the key positive and negative repercussions of work email, as identified from the 2 phases of the research programme.

In the final chapter (Chapter 9) we then provide learning points for organisations and individuals who want to optimise their use of work email. Whilst not providing a one-stop shop for advice on how to manage email, we do hope that this will serve to provide end users with current, evidence-based guidance as we move into the next era of our emailing age.

3. Methodology

There were 2 methodological phases to this programme of research. This chapter firstly outlines the process for conducting a Systematic Literature Review, to clarify the approach taken. Next, the second phase approach is outlined – the sense checking interviews. The interview guide is included in Appendix 4 to highlight how themes, extracted from phase 1, were translated into suitable questions to be validated in phase 2.

The project was conducted in full adherence to university ethics and British Psychological Society ethical guidance. Full ethical approval for this project was granted by Kingston University ethics committee (details available from the author).

3.1 Developing the Systematic Literature Review (phase one)

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) is a state of the art approach to examining the field of literature associated with a particular research question in a systematic, replicable, transparent and scientifically rigorous way (Briner and Denyer, 2012). It helps to avoid the tendency of researchers 'cherry picking' studies that only provide significant results or that support a researcher's pre-established argument. SLRs provide an approach that allows researchers to consider contradictory evidence and non-significant results, and to engage with ‘grey’ literature, not just that from peer-reviewed journals.

In this SLR the focus was on examining work email in 3 areas: incoming (receiving), outgoing (sending), and management of the email system, from the literature looking at email in relations to interruptions, overload, work-life balance, addiction, psychological detachment, and flexible/distributed work. In designing the SLR we developed a search strategy and protocol that was reviewed by an advisory group with expertise either in the research topic and/or in conducting literature searches. Note – SLR Advisory Group is: Dr Emma Russell; Marc Fullman (Research Assistant); Prof Tom Jackson; Prof Kevin Daniels; Robert Elves (Librarian); Dr Pepita Hesselberth.

3.1.1 Setting up a protocol

This is the project plan for the review, and in this SLR we used a framework adapted from Petticrew and Roberts (2008) and recommended by Briner and Denyer (2012). This allows us to specify our search terms and databases, and to set out criteria for including (and excluding) studies to be examined in the review (Denyer and Tranfield, 2009). Accordingly we identified that we would only review studies that included:

1. Working adults using work email only

2. At least 1 application from: sending, receiving and managing work email

3. Outcomes relating to productivity, performance, goal achievement, wellbeing, strain, and engagement

4. Positive or negative repercussions for the above outcomes

5. Empirical studies only (not reviews or opinion pieces)

6. Written in the English language

Following a scoping study and further review of our criteria, we were able to begin our search of the literature, using relevant databases and processes. The SLR proper was conducted on literature available during the week commencing 19th December, 2016. Looking at returns from searches, 2 reviewers (in each case the 2 reviewers were Dr Emma Russell and Marc Fullman) examined whether the paper should be included or excluded in the final literature review. A detailed final protocol is presented in Appendix 1.

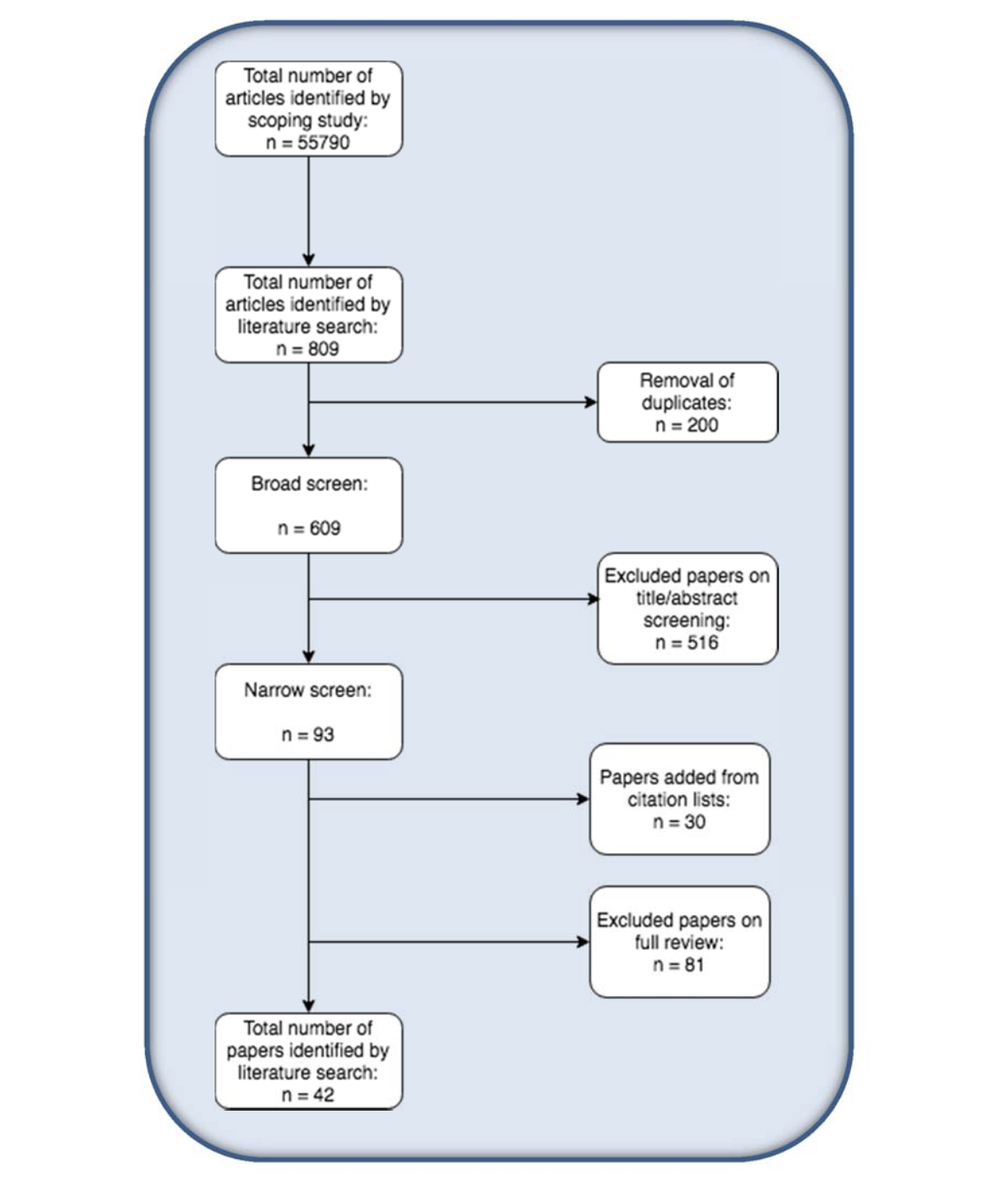

3.1.2 Critically appraising the quality of the literature returned in search results

42 papers were deemed to satisfy the inclusion criteria. The process and findings from the literature search are summarised in 'Figure 1: A summary of papers returned for the SLR at each stage of the process'. The quality of each paper was then independently reviewed by the 2 reviewers. Quality is a judgement; to help make quality ratings as transparent as possible we used a quality checklist based on recommendations by Briner and Denyer (2012), Rojon and others (2011), Walsh and Downe (2005), and Snape and others (2016) (see Appendix 2). Using this approach, each paper was awarded a quality rating out of a possible 9 points, as per Robertson and others (2015). The overall quality rating was 6.9 for the papers returned. The reviewers' independent judgements of quality correlated strongly and significantly, indicating a high level of agreement.

3.1.3 The meta-synthesis

The final 42 papers were gathered and read in full by the lead author in the study. Each paper was reviewed, and written up in a spreadsheet format. From the spreadsheet, an interpretive narrative synthesis approach (Briner and Denyer, 2012; Rousseau and others, 2008) was used to make sense of the findings from each of the papers. This was achieved by using a structural coding approach, as outlined by Corbin and Strauss (1990), and Saldana (2011) – see Appendix 3.

3.2 Developing the interviews (phase 2)

The key themes from phase 1 were used to generate an interview guide, in order to sense-check findings with participants using email at work (representing members from key groups, as studied across the SLR papers). A grounded theory approach was used, whereby the interview guide is flexibly applied and amended on reflection after each interview if necessary (Pidgeon, 2000, Saldana, 2011; Unsworth and Clegg, 2010).

This means that the interview guide does not serve as an unalterable 'script'. For each participant, prompts were used, questions were dropped and additional probes were offered, if this was felt to be appropriate to the understanding of the theme at any point (Pidgeon, 2000). The final interview guide can be found in Appendix 4.

3.2.1 The interview participants and procedure

Twelve participants were invited to be interviewed, via a purposive opportunity sampling approach (Collingridge and Gantt, 2008). From the SLR papers returned, we established key criteria against which representative participants would be sought. For example, because several SLR papers studied participants from technology companies, we wanted to ensure that we interviewed participants from technology companies. For each criteria identified from the SLR papers, we ensured that we had at least 2 interviewees in our sample representing that domain.

Please see 'Table 1: Representation of interviewees participating in sense checking interviews', for the criteria used to identify participants. All participants needed to be knowledge workers (note: a 'knowledge worker' inhabits the primary role of developing and using knowledge, often through analysing and processing information) who used email at work, and were able to access work email both during and after work hours. This was to ensure that the growing trend to access work email beyond the usual constraints of location and hours was available to sample participants.

All interviews were conducted by telephone or Skype and were recorded with permission. These lasted between 40 to 90 minutes, with the majority taking 1 hour. Because the interview questions had been written to reflect the codes from the SLR, the interviews were transcribed using a 'values-coding' approach (Saldana, 2011), with direct quotes captured ('in-vivo coding': Saldana, 2011), if they provided a useful illustration of any theme. Whilst the methodology used here supported the option of amending the SLR coding framework, post interview, this option was not judged necessary (following discussion by the 2 reviewers). The themes extracted from the SLR were deemed to be fulsome and appropriate; only some of the coding labels and definitions required clarification and rewording following the interview phase.

In the next section, the coded themes will firstly be presented. Then, on a theme by theme basis, the synthesis of the literature extracted from the SLR will be presented, with illustrative sense checks and quotes from the interviews integrated into each theme section.

Table 1: Representation of interviewees participating in sense checking interviews

Participant A

Age range: 61+

Gender: M

Organisation type: Academia

Occupational level: Project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 51+

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 50 to 100

Number of email received per day: 50 to 100

Communications used at work: Email, F2F, phone (sometimes), Twitter (occasionally)

Participant B

Age range: 51 to 60

Gender: M

Organisation type: Commercial corporation

Occupational level: Administrative

Hours worked per average week: 31 to 40

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 0 to 25

Number of email received per day: 0 to 25

Communications used at work: Email, Skype for Business, phone, text, F2F

Participant C

Age range: 41 to 50

Gender: M

Organisation type: Large technology corporation

Occupational level: Project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 51+

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 0 to 25

Number of email received per day: 50 to 100

Communications used at work: Outlook, Skype for Business (includes IM), MS Teams (new to MS), project related systems (generates project related emails)

Participant D

Age range: 41 to 50

Gender: M

Organisation type: Large technology corporation

Occupational level: Project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 51+

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 25 to 50

Number of email received per day: 100 to 200

Communications used at work: Phone, mobile phone, Email (Outlook), Skype for Business (IM, phone/video conferencing), MS Teams, Yammer

Participant E

Age range: 41 to 50

Gender: F

Organisation type: Large public sector

Occupational level: Project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 41 to 50

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 25 to 50

Number of email received per day: 25 to 50

Communications used at work: Email, OCS (IM), F2F, text, phone

Participant F

Age range: 41 to 50

Gender: F

Organisation type: Start-up consultancy

Occupational level: Director or equivalent

Hours worked per average week: 31 to 40

PT or FT: PT

Number of email sent per day: 25 to 50

Number of email received per day: 25 to 50

Communications used at work: Phone (mobile, landline), F2F, email, some Skype

Participant G

Age range: 31 to 40

Gender: F

Organisation type: Large public sector

Occupational level: Project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 21 to 30

PT or FT: PT

Number of email sent per day: 25 to 50

Number of email received per day: 0 to 25

Communications used at work: Email (Outlook), OCS (IM, video conference), phone, twitter, iPhone (VPN to allow access to work at home), LiveMeeting

Participant H

Age range: 31 to 40

Gender: F

Organisation type: Charity

Occupational level: Administrative project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 31 to 40

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 0 to 25

Number of email received per day: 0 to 25

Communications used at work: Email (Outlook), Skype for Business (IM), Telephone, F2F, Job Sciences / SalesForce for bulk email

Participant I

Age range: 31 to 40

Gender: F

Organisation type: Commercial corporation

Occupational level: Administrative project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 21 to 30

PT or FT: PT

Number of email sent per day: 50 to 100

Number of email received per day: 50 to 100

Communications used at work: Email (Outlook), mobile phone / iPad (uses to check work email), Skype/IM, text message, phone, Yammer

Participant J

Age range: 21 to 30

Gender: M

Organisation type: Charity

Occupational level: Administrative

Hours worked per average week: 31 to 40

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 50 to 100

Number of email received per day: 50 to 100

Communications used at work: Phone (will shortly have work mobile), Text, Whatsapp, Email (Outlook), Job Science (Salesforce) for customer care, Skype (for F2F), MS Lync (IM)

Participant K

Age range: 21 to 30

Gender: F

Organisation type: Start-up technology

Occupational level: Senior management

Hours worked per average week: 41 to 50

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 50 to 100

Number of email received per day: 100 to 200

Communications used at work: Colleagues, email, Slack, F2F, phone, external (customers), email, HelpScout (shared inboxes), F2F when needed, phone

Participant L

Age range: 21 to 30

Gender: F

Organisation type: Academia

Occupational level: Project / middle management

Hours worked per average week: 41 to 50

PT or FT: FT

Number of email sent per day: 0 to 25

Number of email received per day: 0 to 25

Communications used at work: Email, F2F, phone, Twitter (personal account and journal account), Skype (calls and messaging), Facebook, Gmail

Note: Participants C and D are primary "global workers", meaning they may receive emails from around the world at any time from offices and organisations on different time zones. Some of participants B, H, J, and K's duties meet this criteria.

4. Interpreting the findings

Forty-two papers were returned from the SLR. These are listed in Appendix 5.

Synthesising the results of the empirical papers returned from the SLR, suggests that there are 3 broad themes that impact the strategies that people use to deal with email. Within these 3 themes there are 10 sub-themes associated with the strategies that people use to effectively manage work email. ‘Table 2: Key themes and sub-themes that mutually shape the development of work email strategies’, sets out the framework by which people’s strategic use of email appears to be influenced.

Table 2: Key themes and sub-themes that mutually shape the development of work email strategies

1. Culture

The work criticality of email

The extent to which email is valued as critical to executing and progressing one’s work

Active, embedded email use

The extent to which people have embedded email into their daily work tasks; actively engaging with it throughout the day

Pressure to respond

The extent to which people feel a pressure to respond quickly to incoming work email

Culture of trust

The extent to which ‘trust’ is involved in the email relationships we form, and what happens when trust is missing

2. Adaptation to email use and development

Developing effective strategies

The development of strategies that people believe have improved how they deal with email today.

Addictive/automatic/habitual email use

The extent to which strategies lose their purpose over time, resulting in addictive, automatic and habitual use

Out of hours activity

The extent to which people engage in out of hours activity in relation to their work email

The impact of strategies on different goals

The email strategies and functions that have developed to offer both positive and negative repercussions for workers, depending on the goals being served

3. Individual differences in email experience

Characteristic differences in email activity

The extent to which workers’ jobs, demographic characteristics, or personality (including strategy preference ‘types’) influences perceptions, use and outcomes of work email

Subjectivity of stress and load

The extent to which personal and subjective experiences of email ‘stress’ or ‘overload’ are related to objective reality.

The research programme sought to take a socio-material approach to interpreting the findings from the SLR and sense checking interviews. A socio-material approach asserts that the interaction of the material world (such as email as a technological tool) with the social world (such as individual approaches, work context and cultural norms) impacts a worker’s experience and application of any phenomenon – in this case email. Put simply, by applying socio-materialism as a theoretical framework, we can identify how email as a technology has shaped - and is shaped by - individual strategies for achieving one’s goals within any work or cultural context.

As such, no one aspect of the email experience will be reviewed in isolation from the technology, the person or the work culture. Accordingly, it must be noted that the themes and sub-themes outlined in Table 2 are interrelated and interdependent, reflecting the socio-material application of email (Barley and others, 2011; Orlikowski, 2007). For example, ‘Active, embedded email use’ (Culture theme) can result in ‘Addictive, automatic and habitual use’ behaviours (Adaptation to Email Use and Development theme), and may be especially influenced by ‘Characteristic differences in email activity’ (Individual Differences in Email Experience theme).

Chapters 5 to 7 provide greater depth and analysis of the 3 themes, with Culture and its 4 sub-themes covered in Chapter 5, Adaptation to email use and development and its 4 sub-themes covered in Chapter 6, and Individual differences in email experience and its 2 sub-themes covered in Chapter 7. To aid the reader in extracting salient points, bold type is used to highlight key findings, with important summaries offered in the framed boxes.

5. Culture

As mentioned in Chapter 4, according to the socio-material approach (Barley and others, 2011; Brigham and Corbett, 1997; Mano and Mesch, 2010; Orlikowski, 2007; Wajcman and Rose, 2011; Yates and Orlikowski, 2002), a technology does not exist in a vacuum. Rather, its application and use represents the reciprocal relationship between the functionality of the technology system, its design limitations, and how it is translated and adopted by individuals in pursuit of their goals, within any work context.

In our SLR, we identified 4 sub-themes in which a culture of email use appears to have emerged. These have influenced (and are influenced by) the strategies and behaviours that individuals use to cope with work email, and in turn can be associated with specific work outcomes related to productivity and wellbeing. Further, there are individual differences in the extent to which these cultural categories have impacted people’s work email use; these differences are reported in the section below, and also in the ‘Individual differences in email experience’ Chapter 7.

5.1 The work criticality of email

The development of a cultural norm that views email as critical to one’s work was apparent in both the SLR and for the participants of our sense-checking interviews. Sumecki and others (2011) define business criticality as relating to information whereby, "missing it, ignoring it or failing to optimally exploit it will lead to a significant loss of business opportunity [and when] losing it or misusing it may lead to intolerable managerial consequences” (p.408). We refer to the ‘work’ rather than ‘business’ criticality of email, to encompass the non-commercial organisational use of email. The work criticality of email relates to its criticality as a tool that significantly influences people’s work practices in terms of task and project management, information exchange, scheduling and social communication (Dabbish and others, 2005).

5.1.1 The evolution of a work critical culture

We found - in synthesising the research papers - that email has become more critical to work as its use and application has evolved. For example, Bellotti and others (2005) note how email is no longer considered to just be an ‘add-on’ to one’s other work tasks (supported by Wajcman and Rose, 2011), but is used to manage, prioritise and engage with projects, deadlines and events; operating as a multifaceted, multi-functional tool. Although based on a small sample, by 2003, Ingham had found that 65% people were using email as their communication of choice ‘almost all’ of the time, with 100% of respondents claiming that email was now critical to their work. This ethos was supported by participants in our sense checking interviews. Participants A, B, C, F, I, K and L particularly endorsed the view that email is work critical, with Participant K reporting: “… [email is] critical from a business perspective. It's our main communication for customers.”

However, this evolution appears to have occurred at different paces for different organisations and job types. For example, early technology adopters, the well educated and well paid seem to have embraced email as a work critical tool in several early studies (Fallows, 2002; Mazmanian and others, 2005). Those engaged in highly interdependent work and multiple project strands also view email to be more work critical (Dabbish and Kraut, 2006). Academics however, viewed email as an add-on activity to be left and dealt with at the end of the work day, unlike their non-academic counterparts (Pignata and others, 2015). The extent to which an organisation or individual embraces email as a work critical tool appears therefore to be related to culture and use (Stevens and McElhill, 2000; Sumecki and others, 2011). When a culture of email work criticality develops, this has an impact on outcomes. Sumecki and others (2011) found that those who perceive email as critical to their work feel less overloaded by it.

5.1.2 The work criticality of individual email messages

On an email by email basis, Dabbish and others (2005) and Russell and others (2007) found that the more work critical an email message was, the greater the priority given to it and the quicker one’s response. Ingham (2003) reported that the incidence of non-work-critical email received at work amounted to no more than 4 emails per day; other studies report similarly low figures (Fallows, 2002; Kimble and others, 1998). By 2011, Sumecki and others report the incidence of non-work-critical email to be 8% of one’s daily total, with the work-critical proponents in our sense checking interviews also claiming that email is critical to about 90-95% of their work.

5.1.3 Is email really work critical?

For those who view email as a work critical tool, there is some evidence that this might be a misperception that validates more extreme usage. For example, Mazmanian and others (2005) reported the widely held belief that by not responding to and dealing with email immediately, a crucial piece of information would be overlooked. However, they go on to suggest that this may be a fallacy. Interviewees in their study reported being ‘cc-d’ in on many messages, under the guise that the email was work critical. However, interviewees also reported that in many cases the information contained in the email was not relevant to them and did not enhance their work experience.

Indeed, in our interviews, Participant E reports: “...on the one hand, without [email], it could be argued you can be more productive in some areas and, on the other hand, you can be less productive in other areas. So, percentage wise I would say 40% [of email is] critical to the task.”

It is plausible therefore that a culture perceiving email to be work critical can result in, or represent, a state whereby workers perpetuate the norm of email’s importance, even when (on an individual email basis) the message is not important.

Thus, email can become the default tool by which people convey and transmit work, consolidating the work criticality perception further. This was picked up by Participant J in our interviews. He commented that whilst email would remain work critical when asynchronous exchanges are needed - such as when communicating to global partners - his organisation was pushing towards making email less critical to one’s work. As such, using Skype and face to face exchanges was becoming more integrated into how people chose to transmit their work.

5.2 Active, embedded email use

Related to the development of email as a work critical tool, we found substantial support for the notion that email has now become embedded in people’s work activities to the extent that they are frequently engaged with their email systems throughout the working day, and active in email management.

5.2.1 The evolution of an active, embedded email-use culture

Previous studies on email usage suggest a different picture to its usage nowadays. In 2002, Fallows reported that only 25% of US workers in a large, demographically representative survey, checked email continuously throughout the day, with 75% of workers spending an hour or less on daily email activity. Indeed, in early studies workers reported it was difficult to fit email activity into their normal working day, with email left to fester in the inbox until time allowed for a response to be crafted (Whittaker and Sidner, 1997). Email was often depicted as an unwelcome ‘interruption’ to everyday work activity (Jackson and others, 2003).

As email moved from the dial up and broadband delivery method to always on wifi and 3G/4G use, studies show email use becoming a far more integrated activity (Mazmanian and others, 2005; Wajcman and Rose, 2011). Renaud and others (2006) found that 84% of their participants kept email switched on at all times during the work day (Russell and others, 2007, found this to be 64%; Mazmanian and others, 2005, reported this to be 90%), with 55% keeping work email switched on outside of work hours. People were found to switch between email and their other tasks frequently, with only 14% of work tasks running for more than 5 minutes before the email inbox was checked or dealt with.

Email users may be rather surprised by such figures, including those in Renaud and others' (2006) study, who believed that they only checked their email every 60 minutes. Choosing to switch between work activities (including email activity) was found to be the most common form of interruption to people’s work (65 self-initiated interruptions per day: Wajcman and Rose, 2011). In our sense checking interviews, our participants (especially D, G, H, J, K and L) report that they always have their email switched on and are engaged in a continuous system of checking and dealing with it:

“As it comes in, within an hour, I've actioned it, whether it's, ‘email that person at a later stage’ or, ‘email them straight away’ or just, ‘delete it’. Within an hour, I will have done something to that email” (Participant H).

With the exception of Participant D, the participants listed above are all younger workers (lowest 2 age ranges). Participant E (age range 41 to 50) did not engage with this culture:

“[I am a] strong believer of your emails... not [being] your main priority. You set your main priority of work schedule and emails are just another way of communicating that… [I] try not to be a slave to my email and make them my work priority, as they are somebody else's work priority not mine.”

The development of a culture of embedded use of work email on teams and groups was apparent in several of the studies reviewed. As email is actively engaged with and checked on an almost continuous basis, the norms for dealing with email across a team become standardised. In a focused case study of a small organisation of distributed workers, Im (2008) found that over time workers became increasingly reliant on email to integrate and co-ordinate projects and ideas, and that the way in which it was used became more homogenous. For example project updates began to follow a standardised format, in terms of how the subject line and action points were presented. Greater clarity in the messages evolved, and they became easier to categorise.

Similar findings were reported by Skovholt and Svennevig (2006) in examining the growing embeddedness and standardisation of the ‘cc’ function in a Scandinavian telecoms company. This function became an inherent way in which information was shared, tasks delegated, dialogues encouraged and networks built. In another study (Middleton and Cukier, 2006), email became so embedded in people’s activities that norms for dealing with email during meetings became established, even though users appreciated that this could appear to be rude or disrespectful. It appears from these studies that when email is an active and embedded part of work, its users begin to fall into line with each other, generating their own norms and standards to shape a form of implicit guidance on normative (if not necessarily ‘best’) practice.

5.2.2 The impact of the active, embedded email use culture on workers

There are some interesting results in terms of how people are affected by the ongoing and active daily engagement with email as an embedded part of their work. Barley and others (2011) examined knowledge workers in a high-technology firm. They found that email was highly embedded in people’s daily work and that those who spent more time dealing with email, tended to work longer hours and also perceived themselves to be overloaded, suggesting a negative strain experience. Interestingly however, in Barley and others’s study the same participants also reported that processing more email resulted in greater perceived coping; actually dealing with email and keeping on top of it helped workers to feel in control.

Engaging in heavily embedded email use necessitates, perhaps expectedly, that email volume will increase (Dabbish and Kraut, 2006; Mazmanian and others, 2005; Nurmi, 2011; Russell and others, 2007). However, as found in Barley and others‘s (2011) study, regular clearing and processing of the inbox reduces perceptions of load (Dabbish and Kraut, 2006; Renaud and others, 2006), with some workers reporting that email is far less disruptive than other communication methods (Renaud and others, 2006). These findings have also been replicated with objective measures of load. Kalman and Ravid (2015), using an international sample size of nearly 8,000 working adults, found that workers who are regularly sending, receiving and managing their email have lower levels of overload (unread inbox messages, average response time and inbox size) as they keep on top of their inbox size and respond promptly to incoming messages.

The notion that we may actually reduce our strain experience (sense of overload or loss of control) by actively engaging with our email across the working day is very interesting. There is much to read in the populist time management literature to suggest that we should turn off our email and only check it at set times (such as morning, lunchtime and prior to signing off) in the day. The empirical evidence found in this systematic literature review generally contradicts such advice, suggesting that if we allow our email to build up it may actually create a strain response. The challenge here for workers is to ensure that they keep on top of their email, without allowing it to create invasive and detrimental interruptions (Jackson and others, 2003). Processing (rather than just checking) email regularly throughout the working day (Jackson and others, 2003, suggest every 45 minutes), without necessarily having notifications switched on, could be a solution.

Continuously keeping on top of their email means that workers experience improved self-efficacy (feeling competent and in control) and greater control over the time they allocate to work (Huang and Lin, 2014; Mazmanian and others, 2005; Renaud and others, 2006). It may also result in ‘better’ working. In one study, active email use (sending and receiving email) predicted higher levels of work performance (Mano and Mesch, 2010), although another study found that those who are actively engaged with their email on a frequent basis tended to send and receive less purposeful and less work critical email (Sumecki and others, 2011). However, the Sumecki and others study did not directly measure work performance and it may be that actively sending and receiving more frivolous (rather than work critical) email serves to build work relationships, which consequently enhances people’s work (Mark and others, 2012; Nurmi, 2011).

Our sense checking interviews provide strong support to the notion that regularly clearing email reduces overload:

“I have a pretty (hopefully good) good method. At the beginning of the year I got [my inbox] to zero. I generally try to keep it clean. I don’t like to have lots of things in my inbox because that annoys me. As soon as I've dealt with something I just archive it. I have a folder system that I can put stuff into if I need to and then I... the stuff that is in my inbox is the stuff I haven't dealt with yet. So yeah, I feel quite in control of it” (Participant K).

“Rightly or wrongly it's pretty much open all day. When something pings up it's usually checked... I don’t like a big inbox, I can’t function if that's the case so first thing in the morning, if I'm not in meetings etc., I need to be clear on anything that has come in as a priority, so I do like to keep on top of email” (Participant G).

Participant C, however, appears to be failing to keep on top of email and reports frustration that he needs to deal with email “on top of everything else”, suggesting that email is seen as an add-on, rather than part of his work:

“Now I have 5,000 emails in my inbox. I lost control... I had a big project and I've lost control. There's [sic] too many emails. It's like drinking from a firehose.”

5.2.3 Does email-free time improve work outcomes?

This was measured with both physiological and self-report data in a recent small-scale study, which found that having ‘email-free’ time at work results in a greater strain experience, whereas engaging in email management behaviours (filing and inbox ‘housekeeping’) reduces strain (Marulanda-Carter, 2013). Although length of email-free time and job role was not controlled for in the aforementioned study, this is an interesting result. Indeed, infrequent email access, compared with continuous processing throughout the day, was also related to perceptions of overload in a large-scale survey of global technology workers (Sumecki and others, 2011).

In another study, those who ‘close’ their email, rather than keeping it open throughout the day, were significantly less likely to view email as ‘making life easier’ (Renaud and others, 2006). Causation was not assumed however; people who dislike email will probably close it, and people who close email will probably see it as less useful. What Renaud and others’s study reveals is that people’s perceptions oftheir work effectiveness regarding email may be influenced not only by how they use it, but by their attitude towards email as a worthwhile tool.

In another study where workers were given ‘email-free time’ workload did not diminish and team productivity did not improve – despite increased face to face contact - because the workers felt more cut-off from each other when email was removed However, working without email did result in people switching between tasks less often and taking a more strategic, ‘meta’ view of projects. The pace of work was also found to become more relaxed (Mark and others, 2012). This indicates that active, embedded email use is important to keeping people connected and feeling in control of their work, but it can result in reactive, less focused working.

5.2.4 Embedded use and the blame culture

In understanding the mechanisms behind embedded email use, Barley and others (2011) concluded that email has become both a “source and symbol of stress” (p.887). In effect, those who received greater quantities of email also engage more heavily in other work-related communications such as meetings and telephone calls. However, whilst workers deal with these other communications quickly, they put off dealing with email in busy periods. Workers then begin to experience a sense of overload as the email inbox piles up, viewing this as a symbol that work is getting out of control, and blaming their email volume for this (even though other communications are also high in volume).

This ‘blaming’ culture was also found in a study by Pignata and others (2015) comparing academic with non-academic users at an Australian university. The non-academics integrated email use into their everyday work tasks, checking and filing frequently, rarely allowing inboxes to build up. However, their academic participants reported several problems with their email, seeing it as something they dealt with outside of their working day, because there was not enough time allocation to deal with it as part of their ‘normal’ workload. They then became resentful of this, often deleting emails or becoming frustrated with students who contact them so readily about (what the recipient considered to be) unimportant issues.

Frequent checking has been found to be more likely when a worker is awaiting an email related to their current task, and less likely when the worker is operating to a deadline on another task, or needs to concentrate (Russell and others, 2007).

For example, in our sense checking interviews, Participant F explains: “If I've got really important pieces of work to do I will batch my email. If I [have] got a structured day I will look at it in the morning, I might look at it at lunch time, and then I might look at it in the evening. If I know I've got specific tasks to do, I will block out email. But if I've got an unstructured day, then I might graze on it all day.”

This might explain the differences between academics’ and non-academics’ perceptions of email in Pignata and others‘s study; academics are likely to have work of a highly concentrated nature, and have strict deadlines with regards to submitting funding bids, revising papers for publication, and preparing lectures. As such, because of the nature of their tasks, email cannot be integrated so fully into their ongoing activity. However (from the sense checking interviews), whilst one of our academics (Participant A) demonstrates a clear ‘email as an add on’ approach, another academic appears to be engaged in an embedded approach (Participant L):

“Over the last few months or so I've been kind of consciously trying not to be, to be so reactive... Certainly when that little window pops up automatically it is annoying and encourages you to think, ‘I must go and respond to it’, and that's why I switched it off. When I'm trying to concentrate I don’t want something popping up saying a message has arrived... There are times when I'm aware I'm falling behind on email and I'll spend a whole day going through it” (Participant A).

“I try to manage [email] so it's not ‘a beast over there’. I'm sort of checking on it now and then to keep it under control... I feel like I constantly manage it and that's how I keep up with it. So every time I'm checking email I'm going through that process: filing, dealing with something if I can do it, or marking it to deal with it later” (Participant L).

These studies demonstrate that when email is an embedded part of one’s work, keeping on top of it, and preventing inbox build up is necessary to avoid feeling out of control and overloaded. This may be easier to achieve in different job roles, but is also part of a mind-set, which potentially is more apparent in younger workers (see also Section 7.1.2, Demographic characteristics).

5.2.5 Embedded use, boundaries and expectations

In globally distributed project teams, Nurmi (2011) found that workers had to be very clear about their boundaries (see also the recently published Acas report by Clarke and Holdsworth (2017) on flexible workers, where the need to set clear boundaries and expectations is recommended for distributed workers.)

When email use becomes highly embedded, volumes can increase exponentially, so the worker needs to clarify to what extent (and by when) they are prepared to respond, a finding supported in a study of high-use ‘BlackBerry’ emailers (Mazmanian and others, 2005). Nurmi found that other communication methods can cause people to work longer hours (such as telephone and Skype calls) or exhaust them (such as travelling to meetings) but it is email that has the potential to overload when embedded use continues without clear caveats and expectations.

Nurmi’s study provides an interesting contrast to Barley and others’s (2011) because of its focus on global teams. When time zones are crossed, email is seen as a potential source of overload as it becomes the primary communication method, but unlike in Barley and others‘s study, it does not get the blame for all types of strain, because other methods for communicating across time zones are seen to be more problematic.

Overall then, the active, embedded use of email appears to be a cultural norm that may increase volumes of email sent and received, but which can also facilitate feeling in control and improved work performance; the regular processing and clearing of the inbox promotes self-efficacy and prevents the build-up of messages that can cause people to feel overloaded.

However, embedded use cultures can also create a tendency to deal with email reactively, without thinking strategically about work priorities and projects. Work overload is likely to be an issue for workers receiving high volumes of all communication media, but email is often blamed for the overload, because it is easier to put email to one side when workload is high. Those engaged in high concentration tasks, and potentially older workers, appear to be most likely to reject the active, embedded use norm.

It would be useful in the future for researchers to explicitly study differences in productivity and wellbeing, according to whether workers have accepted or rejected the active, embedded use norm. To add clarity to our tentative findings from the sense-checking interviews, it would also be interesting to include task type and age as potential facilitators/hindrances in such relationships.

5.3 Pressure to respond

In many of the empirical studies reported, participants revealed a strong sense of pressure to respond to incoming email in a very short time frame (Mazmanian and others, 2005; Ramsay and Renaud, 2012). This is likely to be influenced by the cultures of email work criticality and active, embedded use. If email is seen as central to people’s work, and regularly checked - in order to re-prioritise tasks and reply if necessary - then it is understandable why a culture for quick responding will evolve, and in turn validate the work criticality and embedded use cultures.

5.3.1 The evolution of the culture for quick responding

In 2003, Jackson and others reported that 70% of recipients responded to their email within 6 seconds (Thomas and others (2006) report that 70£ of respondents read email within 1 minute), with 85% responding within 2 minutes. As it takes an average of 64 seconds to ‘recover’ from every email that interrupts work, Jackson and others (2003) warn this this norm to respond quickly can result in 102 minutes every day spent ‘recovering’ from regular interruptions. Whilst norms for quick responding are sometimes part of explicit organisational policy, this pressure to respond quickly has developed as a norm that represents customer focus and concern for others (Barley and others, 2011), along with a trust and respect for colleagues (Nurmi, 2011). The latter point was mentioned by participants in the sense checking interviews.

Participant G, despite not having an organisational policy that promotes this, will apologise to senders if it takes more than 2 days for her to fashion a response; Participant J tries to reply within the day to show good service and indorse a good impression of himself. Indeed, workers represented in the empirical papers appear to like responding quickly to colleagues and peers, believing that this prevents a backlog of messages from building up (Mazmanian and others, 2005; Renaud and others, 2006) and will be viewed very positively by the sender (Barley and others, 2011).

In our sense checking interviews, it appears that the culture of quick responding does not indiscriminately result in a hasty reply. It appears that, for some of our participants, the priority of the message will feature as relevant to how swiftly a response is crafted:

“I’ll have a quick look, as we get the little bubble on the monitor, so I’ll have a look and I’ll assess whether or not it needs an immediate response or not. But if not, I know it’s going to be in the inbox as unread, I need to read it at some point but I’ll get from the bubble [whether] I need to actually read the whole email... [If] it’s important... I’ll action accordingly...” (Participant B).

Participant B reports that anything not dealt with during his shift (an average of 15 emails) would be passed on to next shift to deal with. The fact that unread email does not build up to ‘crisis point’ for him, because there are contingencies in place for others to pick up where he left off, may be why the quick response norm does not take precedence over message priority assessments. For other participants, the culture for quick responding is clear:

“I feel pressure to respond quickly.... I would say generally it is the culture of the company to expect quick responses and I think it's due to the nature of the business... expect to request something and it's almost done immediately” (Participant I).

“I don’t know where that urgency comes from. I think it's an internal drive because I like things to be sorted out than to have longer to think about them. So if I can respond more urgently, more quickly I will, if it's not going to disrupt what I'm doing and isn't going to take me too long, I will just respond” (Participant L).

5.3.2 Do senders expect a quick response?

It appears that although workers like to respond to email quickly to show respect for colleagues and service to customer, the perception that senders require a quick response does not necessarily align with actual sender expectations. When speaking from the perspective of a ‘sender’, several studies (and Participant E from our sense checking interviews) report that workers do not necessarily expect that their emails should be replied to as quickly as the ‘receiver’ perspective suggests (Renaud and others, 2006; Thomas and others, 2006; Waller and Ragsdell, 2012).

There are certainly reports that some people (Participant C in our study; or, driven people – Hair and others, 2007) do expect a speedy reply and may apply tricks to encourage this, such as ‘cc’-ing in others, or chasing an email, such as with a follow-up call (Barley and others, 2011; Skovholt and Svennevig, 2006). If such ‘tricks’ are perceived to be present, recipients report a certain level of resentment (Ramsay and Renaud, 2012) and their sense of pressure can increase. Participant H, from our sense checking interviews, provides an example of the sender pressure, when an email had not been replied to instantly:

“Even the other day I got an email from somebody who was in the office so I didn't think it was very urgent. I went away and came back and she resent the email with question-marks. I think we kind of have a tendency where we want a reply right now.”

5.3.3 Quick response norms and strain

Several studies report a tangible impact of the normative pressure to respond quickly on strain (Mazmanian and others, 2005; Thomas and others, 2006). Brown and others (2014) found that this was linked with self-reported emotional exhaustion in their large scale survey of academic and administrative staff at an Australian university.

In their study, when response pressure interacted with email volume, this also resulted in a greater experience of email overload and uncertainty. Nurmi (2011), looking at 10 globally distributed teams, found that the norm to respond quickly developed as email was the central communication method for sharing information and progressing projects.

However, it was reported to have an impact on overload as workers felt compelled to keep on top of increasingly swollen inboxes with a multitude of messages from a multitude of sources, all requiring an expeditious reply. Workers who receive work email through their mobile devices report that because colleagues know they are always accessible, this heightens the perceived pressure to respond quickly; workers consider it stressful to leave a message alone when the sender knows that it has been received (Mazmanian and others, 2005).

There may be individual differences at play here. Hair and others (2007) found that those who view email as a tool that does not require a real time response were less stressed by it and less likely to engage in quick responding, compared with those who viewed it as a synchronous (requiring real time co-ordination and response) tool.

5.3.4 Quick response norms and reactive emailing

A further potential downside of the culture for quick responding is that people may engage in more reactive emailing, rather than giving themselves time to reflect and respond in a strategic or considered way (Mark and others, 2012; Mazmanian and others, 2005). If it takes less than 3 rings of a telephone for most people to respond to an email (Jackson and others, 2003) then this suggests a culture of reactivity and a potential lack of forethought, which can result in decisions being made impulsively (Mark and others, 2012; O’Kane and Hargie, 2011).

In our interviews however, even those who are actively engaged in email use appear able to resist reactive emailing. In the first case, Participant K works autonomously in a small, start up organisation where workers are expected to manage their own time and work in the way that suits them. As such, Participant K will often reply by setting an expectation as to when a full response can be anticipated. In the second case, Participant L does feel some pressure to respond quickly, in her academic role, but exerts self-control when necessary:

“If it’s something that I know requires a little bit more thought then I will resist that, I will resist the drive to reply immediately because I know it's going to disrupt my plan for the day and I will file it for later. In a way, I guess I find the act of filing, the action of doing that helps me feel like I've done something with it.”

5.3.5 Being responsive without being reactive

To deal with the issue of response pressure and reactive emailing, one suggestion made was for workers to set their alerts to arrive every 45 minutes (Jackson and others, 2003). This would mean that email would continue to be checked across the working day (retaining the active, embedded culture necessary where email has become work critical), without the detrimental impact to cognitive processing (such as interruption recovery time: Jackson and others, 2003), decision-making and strain (as mentioned in Section 5.3.1, The evolution of the culture for quick responding). Other studies report that workers are calling for explicit policy on response times, in order to feel both protected from the pressure to respond and better able to exert control over incoming messages (Ramsay and Renaud, 2012). Although note that Renaud and others (2006) report that workers feel better able to control the flow of asynchronous email compared to other communication interruptions.

5.4 Culture of trust

How we engage with email represents - and also depends upon - the trust culture that exists within organisations and between colleagues. In turn, our use of email impacts that trust culture. For example, when there is trust amongst colleagues, an abruptly worded email is less likely to be taken to heart, because the recipient is aware that the sender is probably under pressure, or that this is just part of his/her email style. Equally, if trust is lacking between colleagues, then emails may be routinely saved, as part of an audit trail to ensure that missives can be retrieved further down the line, should agreements break down. In synthesising the findings from the SLR, we found many reports referring to workers’ experiences of the interaction of trust with email use, and the positive and negative repercussions of this culture for them. Additionally, this was an area that gleaned much comment in our sense checking interviews; it appears that trust in email use has a considerable impact on the strategies that people use and how people experience working life.

5.4.1 Norms that reveal a lack of trust

When there is a lack of trust within an organisation, a ‘covering your back’ email norm can emerge that is reflected in: workers ‘cc’-ing, and ‘bcc’-ing in numerous recipients (Kimble and others, 1998; Ramsay and Renaud, 2012; Stevens and McElhill, 2000); presenteeism (appearing to be industrious and hardworking, when little effective work is actually being undertaken such as working when ill; sending copious emails without actually undertaking any productive work), such as avoiding responsibility or broadcasting (O’Kane and Hargie, 2007; Ramsay and Renaud, 2012); and, suspiciously keeping audit trails of email chains (Marulanda-Carter, 2013). These strategies were reported amongst our interviewees in the sense-checking interviews.

Firstly, use of cc is reported to dilute ownership of a project (Participant D) and also to support ‘broadcasting’:

"As head of department, you get copied into lots of stuff, sometimes because people just want to show you they're doing stuff" (Participant A).

"I tend to get frustrated with when you get copied in, when a host of people get copied into emails and then the reply-to-all goes on, when it's not really relevant to you... You could work through 10 emails and think, ‘actually I didn't need to know all of that. I didn't need to be copied in after that first email’” (Participant I).

Then, “presenteeism”:

“[Sometimes, I] procrastinate and use email as an excuse for working, because if I'm seen doing my emails, that's busy and important work <tongue-in-cheek>” (Participant E).

And lastly, audit trails were kept by Participant C, who keeps all email in order tocover his back, and because it may need to be drawn upon in future appraisals.

Further:

“If you don’t have the trust you just have to assume your email is going to go anywhere in the world and be shown... just be very thoughtful of what you put in an email, anything that's been posted to the internet is out there. You just need to be thoughtful [about] using it as a communications tool” (Participant D).

“The... company culture… is a culture of covering yourself so always keep emails to back yourself up and cover yourself if anything was to happen. There's always that culture here. So I tend to keep every single email and file it in the relevant folder” (Participant I).

When email is used to ‘cover your back’ in this way, it arguably not only reflects but exacerbates the lack of trust. Another email management strategy that reportedly causes mistrust and alienation is when managers and colleagues attempt to delegate (O’Kane and Hargie, 2007) and manage their staff using email (Marulanda-Carter, 2013), which is often negatively received because of the lack of mutual agreement or negotiation involved, resulting in perceptions of autocracy and disregard (Stevens and McElhill, 2000).

This was reported by our Participant I as a problem in her workplace. This disregard for others can also be seen in, (i) a lack of responsiveness, whereby email is ignored (O’Kane and Hargie, 2007), and also in, (ii) the use of ‘absent-presence’, whereby workers will engage with email (usually via a mobile device) when they are meant to be physically engaging face to face with other workers (Middleton and Cukier, 2006). Absent-presence was part of the culture in Participant E’s workplace, which – as her other comments in this section might suggest, suffers from a culture of mistrust:

“We do some poor practice, in terms of culture, in terms of using laptops in meetings and people responding and doing emails in meetings. I think we do have a pretty poor culture around that; if not on laptops then on phones.”

Because email is so convenient there is a danger that workers can end up ‘hiding behind’ email; using it to avoid sensitive or controversial conversations, or even to avoid personalised face to face contact (Pignata and others, 2015; Ramsay and Renaud, 2012). Hiding behind email in this way creates a lack of respect and regard for the initiator and can diminish trust (Fallows, 2002). In our study, Participant E concurs:

“I think some people will use email as an avoidance of having a direct conversation and will quite merrily tick that off their task list, job done, when all they've done is sent an email. I see quite a lot of that happening.”

Workers like engaging in face to face and vocal communications with colleagues (Mark and others, 2012), so staff who use email, even when colleagues are proximally close (such as sat at the next desk), are especially poorly regarded (Pignata and others, 2015). This finding was supported by participants in our sense checking interviews:

“We do use [email] as a way to get rid of our to-do lists. Sometimes, we send an email rather than picking up the phone or going down the corridor. The amount of times I have an email from someone who sits 2 desks down from me, which is a real source of frustration for me... Some people say it's an audit trail, but where does trust come into all of this?” (Participant G).

5.4.2 Promoting a culture of trust

On the positive side, email strategies may be used to promote a culture of trust. For example, giving a colleague access to a person’s time outside of work hours (via email) is considered to privilege the relationship, showing the colleague that they are trusted not to exploit this accessibility (Middleton and Cukier, 2006). Email also allows workers to access colleagues across traditional hierarchical boundaries. This is considered to be highly beneficial to junior workers (Mazmanian and others, 2005), although a culture of trust amongst colleagues is necessary to ensure that this will not be exploited (such as by junior members wasting the time of busy managers with inappropriate emailing) (Kimble and others, 1998; O’Kane and Hargie, 2007; Pignata and others, 2015; Ramsay and Renaud, 2012). In our sense checking interviews, evidence of ‘timewasting’ junior members, asking questions they could find the answers to themselves, was a bone of contention:

“The shortest path of least resistance I call it. [It happens] all the time” (Participant E).

However, amongst our participants, it was not just the junior staff who were seen to undermine trust in email use. Participant B reports on evidence of micromanagement by email:

“[My manager] will often pick up emails and answer them for us which is a little bit irritating at times. We do get a sense sometimes [that] he’ll cherry pick emails he wants to respond to and before we’ve had a chance to respond ourselves - or we might be in the middle of responding [and] he’ll respond on behalf us.”

Nurmi (2011) observed how geographically dispersed work teams, with different cultures and language, used email extensively as a means of building relationships with each other, learning about the nuances of respective social exchange norms, and to clarify/remove ambiguity and uncertainty. Using the ‘cc’ function was considered a valued strategy, as it promoted knowledge and information sharing, invited discussion and comment from team members, created a shared resource pool, built relationships and alliances, and shaped norms about how to structure email messages (Skovholt and Svennevig, 2006). A large scale survey of US workers (Fallows, 2002) found that email - as a relationship builder - was seen to be one of its key advantages amongst workers; with workers reporting to feel ‘cut off’ when they cannot have access to email (Mark and others, 2012).

In our sense checking study however, Participant C, who appears to have a lack of trust with colleagues at work (evidenced in ‘back-covering’ and misinterpretation of email), does not believe that email helps to build relationships, seeing a movement to Yammer (a social networking tool that uses approved email addresses and allows users to set up project groups for conversing, sharing files and managing project progress. or MS Teams (shared online workspace to organise groups and projects, manage messaging and share files) as the answer to enabling real time conversations and building relationships in a better way.

Whilst, we suspect, on the basis of the SLR studies reported, that one’s communication tool is unlikely to ‘cure’ a culture of mistrust within an organisation (rather it is likely that problems will simply be transferred to the new medium), Participant J concurs that moving to more personalised face to face communications is likely to build relationships and engender trust, not least because it removes the insidious audit trailing of email.

5.4.3 Misinterpretation of email

Email is considered to be ‘poorer’ in richness than other communication media (for example, contains fewer social cues). This means that although it has developed over time to have more social cues embedded within it (such as use of emojis/emoticons - note: pictorial representations of emotion and tone, such as smiley faces, or thumbs-up - to convey tone) communications by email can often be misinterpreted and misunderstood, which some workers appear to worry about more than others, as revealed by Participant K in our sense checking interviews:

“My boss will write an email and I can see him re-reading it 10 times making the smallest tweaks to it and then he'll be like, ‘can you just read through this?’, and he's very particular about every single thing he writes. Whereas... I'm not too worried about exact wording. I'll often chuck in a few emojis rather than writing anything. I always know what the purpose of it is. I guess I'm also subconsciously aware of who the recipient is and their personality so I just naturally just adjust my tone accordingly, so long as I know the person and then if I don’t... I'll just be aware of that.”