Disclaimer

This is an independent, evidence-based research paper written by Emma Sayers, Amelia Benson, David Hussey, Bethany Thompson, Darja Irdam at the NatCen Social Research.

The views in this research paper are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the author alone.

This paper is not intended as guidance from Acas about the effectiveness of performance management systems.

Executive summary

Background

Performance Management (PM) systems are the processes that aim to maintain and improve employee performance in line with an organisation's objectives. They provide a strategic as well as operational function insomuch as they seek to ensure that employees contribute positively to employer objectives. Their different functions reflect the variety of approaches to PM system design across the public, private and voluntary sectors.

In recent years, the relevance of PM systems has been called into question, set against the context of changing business models, workplace structures, technological developments, patterns of workplace conflict and the needs of a diverse workforce. This research fills a gap for cross-sectoral evidence on how organisations are approaching performance management and their interests and approaches to designing and re-designing PM systems.

Research design

This research set out to distinguish and critically appraise the different performance management processes that are commonly used across organisations of different sizes and sectors, and to identify the principles and values that have application in different PM systems. Additionally, it sought to identify the considerations employers are making when choosing which PM processes suit their needs and best practice for implementing new processes and reviewing existing arrangements.

The complexity of these research questions called for a mixed methods research design, including a quantitative survey of HR and general managers (n=1003), to identify patterns and prevalence of PM systems across the UK, and a deliberative event (n=48), comprising a series of workshops in which participants (all employers – mostly senior HR staff – responsible for implementing PM systems, from a range of organisations) discussed their underlying motivations and beliefs. Following the event, two case studies were conducted to gain deeper understanding of the perspectives of respondents from small organisations in the public and voluntary sectors specifically.

Key findings

Detailed findings from the deliberative workshop and case studies are presented in Chapters 3 and 4 respectively. Analysis of workshop findings reflects the composition of the groups: a range of large and small, public, private and voluntary sector organisations, in each case self-identifying as using ‘formal or appraised-based’ or 'less formal or non-appraisal based' PM systems.

Analysis of survey findings focused primarily on the differences between organisations with what are termed 'highly formalised' PM systems (meaning systems that include performance ratings, personal objectives, annual appraisals and performance development plans) and those with ‘less formal’ PM systems (meaning systems not including all 4 of these components). Survey data was weighted by organisational size and sector to be representative of the proportion of organisations in operation across the UK.

The use and purpose of PM systems

Our research found:

- a large majority of organisations (84%) do not use any kind of PM system, 76% of whom determined that they did not need one, while just 6% would prefer to have one – smaller businesses were especially prone not to operate a PM system

- of those who do operate a PM system, most (85%) have 'less formal' systems, with just 15% using ‘highly formalised’ systems – the use of these ‘highly formalised’ systems was more common in the private sector and among large organisations

- 3 broad values were seen to underpin all organisations’ PM systems, across the deliberative workgroups, broadly irrespective of size, sector and system design –consistency, transparency and fairness

- large, private sector organisations similarly placed a high value on confidentiality and trustworthiness within the PM system, whereas small firms emphasised the importance of a PM system that protected the organisation from legal disputes with employees

- when asked to say what PM systems are specifically used for, a broad range of activities were reported – most common was planning talent and career development (16%), setting individual targets, monitoring individuals' performance against personal objectives and improving productivity (11% each)

- determining pay and bonuses was not prioritised by survey respondents, with only 8% using it to determine base pay and just 1% using it to determine bonus awards – conversely, in the deliberative event, this emerged as an important underlying factor among larger, private sector workplaces, being heavily bound up with the overriding need to have a standardised PM system that allowed for differentiation between employees’ performance

- all organisations represented at the deliberative event prioritised identifying training and development gaps as being among their PM system’s key purposes

- participants from large, private sector organisations reported that the PM system should support employees via mentorship and coaching, to ensure staff development – this view was similarly illustrated by the small, voluntary sector pen portrait, where employee development was seen as a defining principle of performance management, however, only 10% of survey respondents identified planning development and training opportunities as something for which their PM system was used.

The components of PM systems

Although the different components of PM systems were shown to vary, some practices are widespread:

- one to ones between managers and staff formed part of almost everybody’s PM system, even if the frequency of delivery varied; most survey respondents’ PM systems operated a system of annual or biannual one to ones with staff to assess performance (33% and 32%, respectively) – all the organisations represented at the deliberative workshop similarly endorsed the practice of having one to ones as a tool for documenting and recording evidence of performance

- half of survey respondents (53%) are reportedly happy with the current frequency of one to ones, although 28% would prefer to have individual meetings slightly more often – only 6% stated their preference to meet less frequently

- survey and workshop data both point to the fact that digital PM systems are already being implemented in many organisations; in the survey, 60% of respondents confirmed using PM systems that were at least partly online-based –these respondents either judged that online systems are just as useful to an organisation as offline systems (36%) or more useful (59%) and online systems were said to be just as conducive to effecting dialogue between employers and employees (43%) or more so (47%)

-

notwithstanding broad support for online systems, a critical design feature that organisations commonly highlighted as being a performance management challenge was the lack of a quick, user-friendly interface for their online systems, especially among larger firms

-

a strong emphasis was placed on employee self-assessment as the main source of evidence within the PM systems, although top-down managerial feedback was also highly rated. Data from the deliberative workshops suggests that capturing self-reported employee feedback was not valued as a method for documenting performance

-

given this onus on line managers, the importance of supporting them through provision of adequate training and sufficient time and resources in order that they capture feedback appropriately emerges as a key approach for improving performance management delivery, however, the survey evidence indicates that provision of such support is highly variable

Support for current PM systems

Our research found that:

- PM systems were generally valued for contributing positively towards organisational performance, noted across survey responses and workshops and illustrated by the pen portraits – a majority of all survey respondents (57%) determined that their PM systems currently work well, with only 4% stating that their existing arrangements do not, suggesting a general level of (moderate) support for the status quo

- 60% of respondents judged that their PM system was a ‘good way to improve performance’ albeit 9% reported that it actually had a negative effect in this regard

- while 59% felt that employees were ‘strongly motivated’ or ‘somewhat motivated’ by the PM system, almost a third deemed that it had no effect on motivation whatsoever (31%) and 11% called it ‘demotivating’, suggesting a very mixed picture around the role of PM systems in engaging and motivating staff

- many event participants pointed to a lack of consideration for training during the design phase of the PM system and noted that this had led to poor outcomes at the point of implementation – furthermore, using PM systems to improve employee motivation was not prioritised in the survey data, suggesting a possible misalignment between managers’ efforts to enhance workplace effectiveness and their conception of the kind of arrangements that lead to high-performing staff

Reviewing and updating PM Systems

Half of respondents (52%) reported that their PM systems had been reviewed in the last 1-3 years. Of these, 50% were actually changed as a result: 35% of these were simplified, 21% saw the introduction of training for line managers, and 27% involved the adoption of competencies for the PM system.

Organisational reviews of PM systems were most likely to be said to happen on an ‘as required’ basis (reported by 41% of participants), although 35% undertook an annual review to ensure that the PM system was still meeting its aims and goals.

In assessing how well PM systems are working, 36% of respondents reported collecting regular survey data on staff satisfaction with performance management and 38% reported that employees could report their concerns to HR. A similar proportion (41%) did so by checking overall performance of the organisation against targets. While it follows that that feedback is being collected on PM systems, it is possible that this information is being used to determine whether or not a more formal review is ‘required’.

Time spent using PM systems

The time spent using the PM system emerged as an area of shared concern for some managers: nearly a fifth of survey respondents (18%) reported that they spend too much time in this way, rising to a third among those using highly formalised systems (32%). This was illustrated by the small, public sector pen portrait, where performance meetings were said to be too frequent; so much so that they limited the time available for actually meeting targets and objectives.

Despite highly formal systems being perceived as more time consuming, these PM systems were celebrated for being procedurally fair, with consistent processes and controls that were valued by employees.

Furthermore, survey data indicates little appetite for fewer performance management meetings across the board, with only 6% of respondents stating any desire to have meetings less frequently.

This aligns with a view that was in evidence across the deliberative workshops, where individuals reported moving towards more frequent and flexible but less formal performance management meetings (rather than ‘stockpiling’ problems for annual consideration at yearly reviews).

However this shift was not exclusively viewed positively, and raised questions about work-life boundaries and the effectiveness of less formal reviews for improving performance.

Fairness, tailoring and working with employees

More than half (55%) of organisations in the sample had a recognised trade union or employee representative body (ERB); however in only 21% of cases were these groups said to have been involved in designing PM systems (49% reported no involvement, and the remainder were unsure).

Two-thirds of respondents (65%) had a written statement or policy document setting out what the PM system in the organisation is designed to achieve. Of this group, over three-fifths made the policy available to all employees (62%), with a further 21% making it available on request; 18% of organisations with a policy did not share it with their employees at all.

Attitudes towards adjusting and customising PM systems to accommodate different groups of employees varied significantly: half (50%) said that their system was customised for people with flexible work arrangements, such as part-time workers. But only a quarter of respondents (26%) were able to confirm that their PM systems included the option to customise for staff with special needs, disabilities and neurological conditions (the majority being unsure on this point).

Negative attitudes characterised several workshop groups; participants from small, private organisations using less formal systems felt strongly that customising PM systems for specific groups of staff was itself unfair for “everyone else”. Many large organisations, however, promoted the notion of fairness and personalisation of standards and objectives for individuals.

63% of survey respondents judged that their PM system was ‘a fair way of assessing performance regardless of employees' race, gender, age, and personal characteristics’, with only 4% disagreeing with this statement to any extent. The remaining 34% were ambivalent.

Future trends

Findings from both the workshops and survey point to the rapidly growing importance of digital PM systems, with a large proportion of respondents already using online-based systems. More streamlined administration processes, better storage of PM evidence for defending future legal disputes and younger workforces eager for integrated technological systems were all identified as driving the shift towards digital PM system design.

Our data suggests that use of specialised apps and remote digital tools that can be used on laptops, smartphones and tablets will help promote more continual, ‘soft touch’ monitoring of performance, in some measure negating future need for top-down annual performance appraisals.

This shift towards more ongoing, regular performance feedback aligns with an additional trend that was discussed, around the frequency and formality of performance management meetings. Workshop participants expressed eagerness about the prospect of line managers building better relationships with staff, facilitated through more informal management approaches punctuated by more regular, less formal meetings, rather than relying on annual appraisals as a mechanism for improving staff performance and motivation.

Conclusions

Our findings raise concerns that too many organisations give too little space within their PM systems for motivating and developing staff. Employee motivation and wellbeing are leading drivers of organisational development and there is a strong case for PM systems to be rethought and redesigned in order to have greater focus on these areas.

This study highlights some of the important performance management challenges that organisations currently face. Its findings draw attention to several areas of concern regarding the implementation and delivery of PM systems in British workplaces, such as the time-consuming nature of performance appraisals, the need for more and better PM systems training for managers, as well as the persistence of retrograde attitudes regarding the management of employees with additional needs, including disabled staff.

In order to support organisations in establishing effective PM systems that benefit both employees and organisations, more personalised support is needed to improve how performance management is delivered within British organisations. In addition to comprehensive training for managers and HR specialists, best practice advice in the form of straightforward reference materials should be made available to employers. This, alongside proper training, has strong potential to help modernise PM systems and increase their fairness and inclusivity.

1. Introduction

1.1 Research context, rationale and aims

Performance Management (PM) systems are the set of processes that aim to maintain and improve employee performance in line with organisational objectives. They provide a strategic as well as an operational function, aimed at ensuring alignment between employee work plans and the goals and direction of the organisation. There are a variety of different approaches to PM systems in the public, private and voluntary sectors. Systems vary by formality and are often adapted to match organisations’ size or operational focus.

NatCen was commissioned by Acas to carry out research into PM systems, in the context of recent changes to how these systems are being used by employers. Current debates on PM systems have focused on growing uncertainty about their relevance and value, with attention drawn to prominent examples in the private sector of large companies moving away from appraisals and performance ratings – 2 of the defining features of traditional, formalised PM systems – in favour of a variety of different processes (see 'The Performance Management Revolution', Harvard Business Review 2016).

There has been a change in expectations about what kind of PM systems work well, but also a discussion around the impact of the different systems on employees and workplace relations, and their capacity for aligning individual with organisational objectives. The relevance of PM systems in particular, is called into question in the context of changing business models, workplace structures, technological developments, the rise in conflict associated with PM systems, and our increased understanding of the needs of a diverse workforce (including but not restricted to workforces that are neurodiverse) - see 'Neurodiversity at work', National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

Furthermore, this context of change extends beyond the private sector, with four government departments (HMRC, the Department for Work and Pensions, the Ministry of Defence, and the Home Office) having announced changes to the way they manage employee performance. The withdrawal of forced ranking across the senior Civil Service has been a key driver for departments to also remove their guided distribution systems. A fresh emphasis has been placed on PM systems that operate as a developmental, two-way process – rather than top-down, pay-focused approaches – as part of a wider move towards granting more flexibility for departments to (re)design their own PM systems. These changes draw attention to the need for a discussion of the role of performance management in the public as well as the private sector.

Research in this context is necessary given the dearth of cross-sector information on how organisations approach performance management, and their interests and approaches towards PM system re-design. While there has been a broad discussion about the growing shift towards using more ‘informal’ PM systems, questions remain about what this will mean in practice and how this affects other areas of employment relations.

Employers and employees need clarity on how different PM systems work in reality, and what some of the practical considerations for each type of system would be. For example, as new online PM systems are developed which can record employee engagement electronically and monitor performance patterns across an organisation, there is a need to understand what effect this might have on HR and people management. This particular research is not concerned with wider HR policies and focuses specifically on the role of PM systems.

The findings from this research will not only help Acas to evaluate these new systems and inform its new guidance in this area – and future good practice service delivery – for employers, but also guide Acas in terms of redesign of its own PM system.

1.2 Research questions

The aims of our research were to address the following questions:

- what types of formal and informal performance management processes are commonly used across different sectors, industries and organisation sizes, and what are their merits and limitations?

- is it viable to identify a series of principles or values that apply to all PM systems, in the knowledge that no one-size will fit all, which should take priority – best practice or ‘best fit’?

- what should an employer consider when choosing which process best suits the needs of their organisation?

- what is the best approach to implementing a new performance management process within an organisation – both where there is no existing scheme, and where a transition is required?

- what questions should employers ask when routinely reviewing their current PM systems?

1.3 Methods

In order to answer these research questions, the study involved mixed methods research methods:

- A quantitative survey of HR and General Managers to gather information on different approaches to performance management being used in the UK, using an online panel. Questions focused on the types of PM systems that organisations are using and their views on these systems.

- A deliberative qualitative research event with employers from the public, private and voluntary sector to discuss their own PM systems, what informs them, what some of the key elements involve and what the issues are around designing and implementing such systems.

Data from the survey was used to identify patterns and prevalence of PM systems across the UK, while the event itself was held to probe employers’ underlying motivations and beliefs. Using these 2 methods for the study has provided us with a range of insights into these 2 areas of interest.

1.3.1 Survey

The survey had a 10-minute completion time and featured 30 questions. Respondents were pre-profiled panellists who were identified as working in HR or as a manager or higher in their company, working across a variety of sectors, industries and size of organisation. Analysis of survey data has been largely descriptive, focusing on analysis by key characteristics such as organisation size and broad industrial sector.

1.3.2 One-day deliberative event

A one-day deliberative event with 48 employers from the public, private and voluntary sectors was held in February 2018. A deliberative event is comprised of a series of focus groups on similar topics or issues, allowing participants to discuss and develop their ideas over the course of the day. The event was held in Birmingham as it has the biggest economy outside of London, and was recently reported as the fastest growing economy outside of London.

The primary sample criteria included size, sector and type of PM system used. Quotas were agreed for each characteristic to ensure the structure of the sample achieves the required coverage. Seven NatCen researchers attended the event with one facilitator per group. Each facilitator, with permission from participants, used an encrypted digital recorder to record group discussions, as well as taking detailed notes.

The focus groups used a topic guide to facilitate discussion in 3 separate workshops, the content of which are displayed below.

Deliberative event workshops

Workshop 1

The purpose and need for PM systems: the reasons behind PM systems.

What do PM systems look like? Identifying the key principles and components of the employer PM systems, the steps, the approaches and the channels used in each component. Do they work?

Workshop 2

Exploring main issues and challenges in relation to PM systems. This includes identifying what works well and less (including possible solutions) in designing and implementing PM systems.

Views on Acas’s draft guidance: Consider 2 or 3 straw man elements – reaction and critique

Workshop 3

Future directions for PM systems. Revisiting the purpose of PM systems with a view to identifying future trends in the design and implementation of PM systems, including what motivates, is perceived as valuable and concerns participants.

Exploring how Acas can best support organisations. Here the focus is on how Acas can present its guidance and promote it in a way that helps. What other support could Acas provide?

Qualitative data from the deliberative event was analysed using NatCen’s framework approach, which facilitates robust qualitative data management and analysis by case and theme within an overall matrix. Matrices were developed through familiarisation with the data and identification of emerging issues. The team then established the range of circumstances, views and experiences, identifying similarities and differences and interrogating the data to seek to explain emergent patterns and findings. This was also triangulated with flipchart notes that researchers took during the event.

1.4 Report structure

This report will discuss the findings from the 3 elements of research in turn.

Section 2 covers the survey findings, presenting a descriptive overview of the results, together with bivariate analysis that explores differences between 'formal' and 'informal' performance management systems and considers associations between certain organisational characteristics (size, industrial sector) and how systems are used.

Section 3 addresses the findings from the deliberative event workshops by considering employers' views on the theoretical foundations of PM systems, the practical challenges for designing and implementing PM systems and finally looking at future trends. This section concludes with a discussion of Acas’s role in supporting good PM system design.

Section 4 reviews 2 pen portraits used as case studies for small, public organisations and small, voluntary sector organisations, recruited from participants who attended the deliberative event and presented here to illustrate in greater detail some of the themes from the event.

Finally, section 5 concludes with a synthesised summary of the findings, considering implications for policy and practice and making some observations about the future.

2. Survey findings

An online panel survey of UK organisations was conducted in March 2018. The data from this survey are reported in this chapter. The full survey data tables are presented at Appendix 33. The survey sought to determine the prevalence of the types of PM systems that organisations use across the UK and enumerate employer views and experiences of using these systems. To this end, 1,003 panellists were selected by Research Now, an online market research agency. These were pre-profiled panellists who were identified as working in HR or as a manager or higher in their company.

2.1 Survey methods

Weighting of the sample

The sample was weighted by organisational size and sector to be representative of the proportion of organisations in operation across the United Kingdom using the ONS data on UK business; activity, size and location (2017). This ensured the data was adjusted to overcome the over-representation of the public sector and large sized companies and the under-representation of private, small organisations.

Where sub-group analysis is reported, it should be noted that due to weighting, the effective base sizes are relatively small, resulting in large confidence intervals. Where differences are reported between one sub-group and others, unless otherwise stated, the finding is statistically significant (p<0.05 meaning we can be 95% certain that the finding is an accurate estimate of the population). Further details are given at Appendix 3.

Types of PM systems used by survey respondents

The initial results of the survey were used to derive new variables, which served to differentiate those panellists with highly formalised PM systems from those with less formal PM systems – a key analytical break for this study. Simply put, this was done by separating respondents according to whether or not they use performance ratings and objectives-based appraisals (2 defining features of a ‘formal’ PM system, as traditionally conceived).

More specifically, respondents who confirmed that their organisation used a PM system were asked whether it 'includes a process for giving employees performance ratings' [CQ3], with 3 possible response options:

- no

- yes, with forced/guided distribution among the different performance categories

- yes, but without any forced/guided distribution among the different performance categories

Those answering ‘no’ to this question were classified as having a ‘less formal’ system. Respondents answering ‘yes’ (either with or without distribution) were routed to a further question (CQ4) which asked them to specify which activities and processes were used as part of their PM system. Only respondents who indicated that their PM system used all 3 of the following processes were coded as having ‘highly formalised’ PM systems:

- Assessment against personal objectives [CQ4_1]

- End of year performance appraisals/reviews [CQ4_3]

- Performance Development Plans (PDPs) [CQ4_5]

Anyone whose organisation used just 1 or 2 of these features was classified as having a 'less formal' PM system (alongside those panellists who had previously indicated that their PM system did not give ratings at all). Only significant findings were included in the report unless otherwise stated. Where differences are reported on in the text between one sub-group and others, unless otherwise stated, the finding is statistically significant (p<0.05; meaning we can be 95% certain that the finding is an accurate estimate of the population). Where sub-group analysis is reported, it should be noted that due to weighting, the effective base sizes are relatively small, resulting in large confidence intervals.

2.2 Characteristics of survey respondents

Respondents’ personal characteristics were examined to show their age, gender, job role and proximity to HR. There was a fairly even spread of genders, job roles and ages, although most respondents did not work in HR directly.

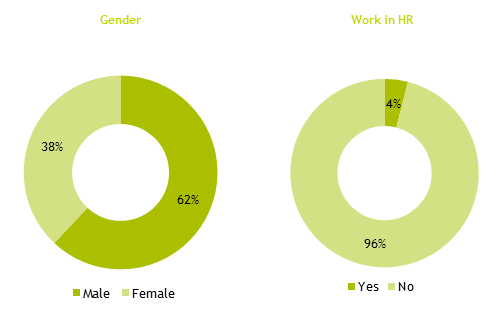

There were 1003 respondents to the survey, 62% of whom were male and 38% female (Figure 2, Table AQ1). A variety of ages were represented; ONS data from 20185 determined that 75% of the labour market is aged 16-64, whereas 87% of survey respondents were aged 18-64 (Figure 2, Table AQ2). The use of an online survey platform may have resulted in the underrepresentation of over 65 year olds in the survey (13%) compared to these national estimates (25%). Managerial roles were highly overrepresented in the survey compared to national levels (Office for National Statistics. 2017. EMP04: Employment by occupation) however this is due to the inclusion of managerial roles as sampling frame criteria. The most commonly held job role for survey respondents was ‘Director’ and ‘Managing Director’ (45% combined), with ‘Senior Manager’ and ‘Manager’ accounting collectively for 17% (Figure 2, Table AQ3). Notably, only 4% of respondents themselves worked directly in an ‘HR’ role. It is important to note that the smallest organisations may not have a separate HR function, which may explain the low proportion of respondents working in designated HR roles (Figure 2, Table AQ6).

Weighted base: 1003

2.3 The structure and components of performance management systems

An initial series of questions asked respondents about whether they used a PM system at all and, where they did, how it was designed, what functions or aspects it gave priority to – and in support of what overall purpose.

2.3.1 The spread of PM systems

All survey respondents were asked at the outset whether their organisation used any performance management systems, with results being split markedly between those that did not have a PM system (84%) and those that did (16%); 13% having just one system for all staff members while 3% had multiple PM systems for different groups of staff (Table CQ1).

Perhaps not surprisingly, smaller businesses were especially likely to lack any formal PM system: 88% of micro sized businesses did not have a PM system in comparison to 44% of small, 39% of medium and 28% of large sized organisations (Table CQ1.a). In addition, 69% of the public sector and 86% of the private did not have a PM system (Table CQ1.b).

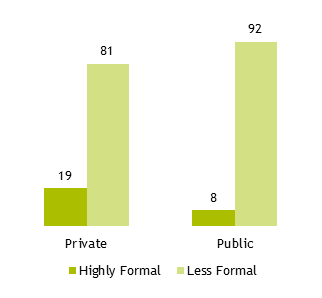

Using the ‘highly formal or less formal’ variable described in 2.1 (above), just 15% of those operating PM arrangements emerge as using what we class as a ‘highly formalised’ PM system, compared to 85% whose organisations use a ‘less formal’ system (Table CQ3.a).

The relative preponderance of ‘less formal’ systems over ‘highly formal’ systems was found to extend across all the industrial sectors and organisation size bands. For instance, more than three-quarters of private sector organisations used ‘less formal’ systems (81%), as did 92% of public sector panellists (Figure 3, Table CQ3.b). Overall, what we class as ‘highly formal’ systems were somewhat less used in the public and voluntary sectors than in the private sector.

However it should be re-stated here that our ‘highly formal’ classification is artificially strict, resting as it does on 4 discrete sub-components (such as performance ratings, personal objectives, annual appraisals and PDPs). Moreover we are reporting respondents’ perceptions of the structures of their PM systems, which may in some cases be inexact.

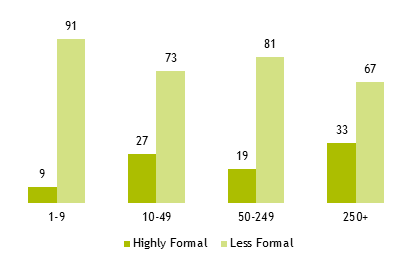

As might be expected, when a comparison against the size of the organisation was made (Figure 4, Table CQ3.c), it emerges that ‘highly formal’ PM systems were more commonly used in large organisations (of over 250 employees), 33% of which used such systems, compared with 9% of micro sized (1 to 9 employees) organisations. Nevertheless, as with industrial sector, less formal systems were preferred across the size bands.

All respondents whose organisations do not use a PM system (Table CQ1) were asked whether this was something that should be introduced: over three-quarters (76%) said that they did not think they needed one, while just 6% said that it would be a good practice to have one (Table DQ14).

These respondents are necessarily excluded from the statistics that follow, which are based on responses to a suite of questions about how people’s PM systems operate, and hence were only asked of individuals actually working in organisations which have some form of PM system.

2.3.2 The use and purpose of PM systems

Those respondents with a PM system were asked to classify its primary functions, meaning to say what it is mainly ‘used for’. This was a multiple choice question, with respondents able to choose more than one option.

There was a broad spread of responses, with 4 options each being selected by more than 10% of respondents: 16% judged that their PM system was used mainly to plan talent and career development for the future, while setting individual goals and targets, monitoring the performance of individuals against personal objectives, and improving the productivity of the organisation were each selected by 11% of respondents.

Conversely, few organisations use the PM system to determine financial awards, with just 8% and 1% respectively using it to govern the level of base pay awards and bonus payments (Table CQ14).

The fact that only 10% of respondents confirmed using their PM system for in-job training and development is particularly notable given that ‘future talent/career management’ was the most-selected option.

This may suggest that PM systems are more likely to be seen as a tool for developing specific individuals who are of particular value to the organisation (to generate business value), rather than to support organisation-wide learning and development in a more generalised way (to get the best out of the workforce by developing skills and capabilities more widely).

Moreover the spread of other responses indicates a tendency for PM systems to be used for improving organisational productivity and performance in a way that is divorced from, rather than supportive of, staff motivation and engagement (Figure 5, Table CQ14).

Notwithstanding the overall pattern of response illustrated above, when the data are stratified by sector, several key differences emerge.

For example, 20 of public sector respondents reported using their PM system to monitor the performance of individuals against personal objectives, a figure which drops to 9% among private sector respondents. Similarly – and not surprisingly – 10% of private sector respondents reported using their PM system to increase the financial performance of the organisation, compared to less than 1% of public sector respondents.

Even more pronounced sectoral differences are in evidence regarding use of PM systems for ‘planning future talent and career development’, selected by 36% of public sector respondents but only 11% of their private sector counterparts, who were similarly much less inclined to use PM systems for planning and monitoring training and development opportunities (6%, versus 25% public), suggesting a strong sectoral imbalance in terms of using PM systems for staff development.

Differences were also seen in using PM systems to set individual goals and targets (14% private versus 3% public) (all figures Table CQ14.a).

These results do not sit entirely neatly with responses to another question, positioned towards the end of the survey, that asked respondents to say how the data collected from their performance management systems are actually ‘used by management’ (Figure 6, Table DQ2).

Here, respondents were most likely to report that their PM system data was used to improve training plans (40%), with around a fifth of respondents using it for promotions (19%), equality and diversity work (19%), and making pay and bonus judgements (17%) (Figure 6, Table DQ2). There is something of a prima facie tension here with the earlier results, where low proportions of respondents had reported using their PM systems for determining pay awards and bonus payments.

It is possible that, for some organisations, although PM systems are primarily being used for non-pay based activity – such as monitoring employee performance against targets – the results of these activities are nevertheless used to inform secondary decisions regarding performance-related pay.

This notion is corroborated by findings from the deliberative event, reported in section 3.2, specifically in respect of large private sector organisations.

In addition to these questions about what specific functions PM systems are used for, respondents were also asked to reflect much more generally about how their performance management system is ‘mainly used’ (Figure 7, Table CQ2), with 3 broad options given:

- to rate past performance and results

- to support training and development

- a combination of both these approaches

Here, respondents were most likely to report that it was used for a combination of rating past performance and supporting training and development (47%) – with the remainder being split fairly evenly between those whose PM systems were used purely to rate past performance (25%) versus those whose PM systems were centred on supporting training and talent development (28%) (Figure 7, Table CQ2).

It is notable that such a large majority of respondents (75%) identified training and talent development as being a main use of their PM system – either in its own right or in combination with rating past performance (Figure 7, Table CQ2) – given that prior responses illustrated at Figure 5 showed this as being much less of a priority (particularly among private sector respondents). This may suggest a mismatch between what managers in an organisation think the PM system is or should be used for, and what the system is used for in practice.

In line with the above findings, in response to a related, subsequent question on the use of ratings specifically, three-fifths of respondents confirmed that their PM systems did include a process for giving employees performance ratings – a third awarding these based on forced or guided distribution among the different performance categories (34%), and a quarter awarding them without forced or guided distribution (24%). The remaining two-fifths (42%) of organisations did not give employees any form of performance rating (Table CQ3).

When the data were disaggregated, micro-sized organisations emerge as being more likely to have ratings-free PM systems than larger organisations (Figure 8), although this difference is not statistically significant. Organisations with ratings systems were more likely to operate a system with forced or guided distribution, regardless of organisational size (Table CQ3.d).

Going beyond the narrow issue of performance ratings, respondents were presented with a list of 7 more fundamental PM activities or processes and asked to say which were included in their own PM systems. Between a third and a half reported that their systems included end of year performance appraisals or reviews (46%); performance development plans (42%), and assessment against personal objectives (32%) (Figure 9, Table CQ4). It is striking that just 25% of organisations linked individual objectives to the organisation’s overall mission or strategy, despite this being a defining feature of PM systems as traditionally conceived.

Large organisations were far more likely to use PM systems that link an individual’s objectives to the organisation’s overall mission, reported by 47% – compared to 20% of micro, 33% of small and 42% of medium-sized organisations (Figure 10), indicating a trend whereby the larger the organisation, the more likely it is to link staff objectives to its overall mission (Table CQ4.b).

Elsewhere, industrial sector was correlated with linking the PM system to financial rewards, such as performance related pay or bonuses. A quarter (26%) of respondents from private sector firms did this, compared to 18% of their public and sector peers (Figure 11). This echoes findings from the deliberative workshops in section 3.1.2, where a focus on performance related-pay being the norm was suggested in private sector groups (Table CQ4.a).

This same pattern of response was reflected in the results to a subsequent question, where respondents were presented with 8 possible measures of performance – different dimensions of meeting targets or assessments of staff performance and behaviours – and were asked to say which ones their own PM system prioritised. 45% said that their PM system prioritised meeting individual targets, with employee self-assessment of performance (43%) and manager feedback on performance (35%) also featuring heavily (Figure 12, Table CQ7).

Targets were prioritised by more organisations than were behaviours, with around one-third reporting that manager feedback on behaviours was a priority (30%) and slightly fewer reporting employee self-assessment on behaviours as a priority (24%). Peer-to-peer feedback was seen as a lower priority in performance management, both in terms of feedback on performance (21%) and feedback on behaviours (17%) (Table CQ7), which tallies with findings from the deliberative workshop reported at section 3.1.1.

2.4 Components of the performance management system

A short series of follow-up questions asked respondents to comment on 2 specific components of their PM systems –their use of online platforms, and the frequency of meetings currently being undertaken as part of existing arrangements.

First, respondents were asked to say how often managers at their organisation have one to ones with staff as part of their PM system (Figure 13, Table CQ5) – varying frequencies were reported, with almost all respondents (99%) reporting that meetings were held at least once per year.

A third (33%) of respondents reported that these meetings were held annually; for a similar proportion (32%) they were twice-yearly events, with monthly one to ones being reported by nearly a quarter of respondents (22%). Fortnightly, weekly and daily meetings were far less common – reported by 3 percent, 3% and 6% respectively (Table CQ5).

Almost half the respondents were happy with the regularity of meetings, with 53% stating that performance meetings and discussions should continue “with the same frequency”. There was little call for fewer meetings, with only 6% of respondents wishing to have meetings less frequently (Figure 14, Table CQ6).

When the current frequency of respondents’ one to one meetings is cross-tabulated with respondents’ assessment of how often these meetings should happen, the spread of data is would be expected (Figure 15, Table CQ6.a) insofar as those most likely to call for more frequent one to ones were the respondents who currently have them least (71% of those who never have them and 55% of those who have them annually).

The fact that nearly three-fifths of those who already have ‘daily’ performance discussions said the same may suggest that these respondents – few in number – were conceiving of one to ones as little more than informal conversations. More instructive is the fact that three-quarters of those who had monthly (76%), fortnightly (80%) or weekly (73%) meetings wanted this frequency to be maintained.

Next, respondents were asked a series of questions about their use of online PM systems. In the first place, 60% of respondents reported that their organisation’s PM system was at least partly online-based – 18% exclusively so (Table DQ5). Of these, over a third (36%) found that ‘online and offline PM systems are equally useful to the organisation’; 40% judged that online systems were ‘somewhat more useful to the organisation’ and 19% found them ‘much more useful’, suggesting that respondents are happy to use online-based PM system in the workplace – or at least, do not feel that they are detrimental to the PM system process (Table DQ6).

A final question asked respondents to comment on the relative effect of online-based systems on the stimulation of dialogue between employers or HR and the organisation’s employees: nearly half (47%) of respondents felt that an online-based system was more likely to stimulate a dialogue between employers and employers, with slightly smaller proportion (43%) reporting that online-based and offline PM systems had the same effect on the dialogue between employers and employees. Meanwhile, just 1% said that using an online-based system would be likely to actively prevent such a dialogue (Figure 16, Table DQ8).

2.5 Efficacy of current performance management systems

A further set of questions asked respondents to comment on how well they their PM systems were currently functioning overall, specifically with regard to motivating employees and actually improving their performance.

There was varied approval among respondents for the PM systems currently in place in their organisations. More than half of all respondents agreed (to varying degrees) that their PM system works well for the organisation (57%), while only 4% ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’, suggesting a general level of support for the status quo. However, 39% of respondents ‘neither agreed nor disagreed’ that their PM system worked well, and moreover where agreement was registered, this tended to be at the lesser level (‘agree’ rather than ‘strongly agree’), suggesting that the prevailing mood is one of ambivalence rather than active endorsement (Table CQ15).

There was a similar response pattern among respondents when asked if their PM system was a ‘good way to improve performance’: 60% agreed that it was, with 32% ‘neither’ agreeing nor disagreeing. The remaining 9% ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’ that their PM system was good tool for actually improving employee’s performance (Figure 17, Table CQ16; totals do not add to 100% due to rounding).

Conversely, in response to a subsequent question about the effect of PM systems on staff motivation, respondents were less positive: three-fifths (59%) felt that employees were ‘strongly motivated’ or ‘somewhat motivated’ by the PM system, while 31% deemed that it had no effect on motivation whatsoever (Figure 18, Table CQ20).

Moreover, it seems that where staff motivation is improved, this may be happening as a welcome but inadvertent by-product of a good PM system, rather than something more designed, given that only 7% of respondents had earlier identified ‘employee motivation’ as being a purpose of their PM system in the first place (Table CQ14).

A further indicator of the quality of performance management arrangements is the training of managers in how to use PM systems. Three-fifths of respondents confirmed that line managers receive formal training (a course or workshop organised by the employer) in how to use the PM system (58%), while a further 25% said that they did not know, meaning that this number may conceivably be higher (Table CQ12). In half of all cases where it did occur, training was compulsory (51%), although, again, there was a high proportion of respondents who did not know (24%) (Table CQ13).

2.6 Reviewing and updating performance management systems

The survey explored several aspects of the PM system review process, with respondents being asked to comment on the nature and frequency of such reviews and the changes effected by them and to say how time-consuming they found their organisation’s PM system.

Respondents were asked to say whether their PM system had been reviewed in the last 1-3 years: half (52%) answered in the affirmative (Table CQ8), with half of this group (50%) also reporting that their PM systems had actually “changed as a result of this review” (Table CQ9). Here, the most commonly reported changes were simplification of the system (35%), the introduction of training for line managers (21%), and the introduction of competencies (27%) (Table CQ10).

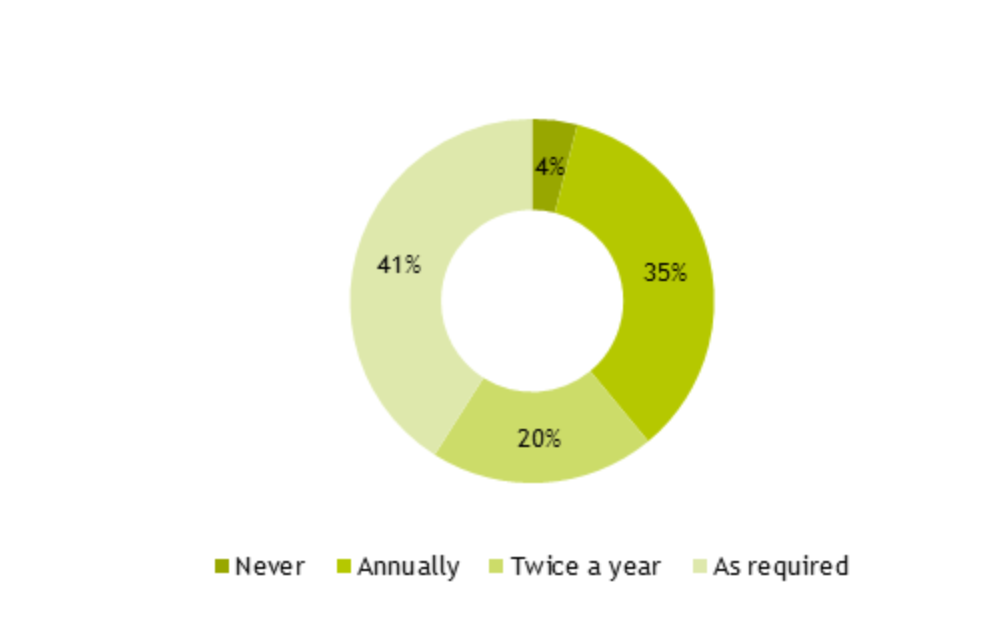

In terms of regularity, organisational reviews of PM systems were most likely to be said to happen on an “as required” basis (reported by 41% of participants), with 35% reporting that they undertook an annual review to ensure that the PM System was still meeting its aims and goals. Just 4% of respondents reported that reviews of the system “never” took place in their organisation (Figure 19, Table CQ11).

When asked to say what evidence their organisation has on how well the PM system is working, 36% of respondents reported that they collected regular survey data on staff satisfaction with performance management, while 41% did so by checking overall performance of the organisation against targets (Table CQ17). While it follows that that feedback is being collected on PM systems, it is possible that this information is being used to determine whether or not a more formal review is ‘required’, as the aforesaid 41% of respondents reported was their practice (Table CQ11).

Respondents were also asked if they thought their PM systems should be changed or updated. A clear majority were open to this idea, although the degree of appetite for change varied: 26% said that their PM system ‘could benefit from changes or adjustment’ and more than 1 in 8 judged that it should be ‘changed significantly’ (13%). However, a large proportion of respondents did not mind whether or not adjustments were made (32%) (Figure 20, Table CQ21).

The 3 main changes that were supported by participants included: more personalisation for individual employees (40%); greater fairness (24%) and system simplification (18%) (Table CQ22). These calls for more personalisation and greater fairness align closely with the results for 2 further questions reported in section 2.8, where respondents were asked directly about the processes that govern the fair operation of their PM systems and the degree to which PM systems are adapted for individuals.

Respondents’ support for simplification of the PM system here is further reflected in their responses to a subsequent question that asked them to say how time-consuming they found their organisation’s PM system. Here, just under half (49%) reported that they spent the right amount of time on performance management, with the remainder being evenly split between those respondents who felt that they spent too much time on performance management (18%) and those who judged that they spent too little time (21%) in this regard (Table DQ1).

As might be expected, respondents using ‘highly formal’ PM systems were more likely to determine that they spent too much time on their system; 32% compared to 16% of respondents from organisations with a less formal system (although this is not a statistically significant difference). Similarly, 22% of those using less formal systems (but only 15% of highly formal system users) reported that they did not spend enough time on performance management, which may be a reflection of the kinds of less-structured systems highlighted in some of the deliberative workshop groups. (Figure 21, Table DQ1.a)

2.7 Fairness, tailoring and working with employees

Finally, respondents were asked about several aspects of how PM systems work for staff with reference to the involvement of employee representative bodies, the degree of customisation offered for different groups of employees and steps taken to ensure fair operation of the PM system.

Respondents were split fairly evenly between those whose organisation featured some form of employee representation – specifically the 55% who either recognised a trade union, employee representative body (ERB), or, in a minority of cases, both – and the 45% whose organisations did not, as shown in Figure 22 (Table CQ18).

Respondents working for organisations that recognised a trade union or ERB (55%, Table CQ18) were asked whether these groups had been involved in designing the PM system at its inception: 21% confirmed that these groups had been involved, while nearly half of those questioned (49%) reported that this had not happened. A third of respondents (22%) did not know either way, which may be due to the age of the PM system or indicative of the position of the respondent; further research is required to investigate the role of trade unions and ERBs in PM system design (Table CQ19).

Elsewhere, all respondents were asked whether their organisation had a written statement or policy document setting out what the PM system in the organisation is designed to achieve. Two-thirds of respondents confirmed that this was the case (65%, Table DQ3); of this group, over three-fifths made the policy available to all employees (62%), with a further 21% making it available on request. Just 18% of organisations with a policy did not share it with their employees at all (Table DQ4).

Three further questions asked respondents to say whether their PM systems were specifically customised for various different groups of staff – in the first instance, for different levels of seniority and types of staff (for example. white and blue collar). Here, the picture was very mixed and characterised by uncertainty: a third of respondents (33%) confirmed that people at different levels were assessed based on different criteria, while 39% reported that all employees were assessed using the same criteria; a further 27% did not know (Table DQ9).

The second dimension of PM system’s customisation that was explored concerned working arrangements: half of respondents (50%) said that their system was customised for people with flexible work arrangements, such as part-time workers, while a quarter (24%) said that this did not happen. Again, a quarter of respondents (25%) were uncertain either way (Table DQ11).

However, there was a positive association between the use of so-called ‘less formalised’ PM systems and the customisation of systems for people with flexible work arrangements: with 50% of those using ‘less formalised’ systems reported the option to customise in this regard. It is perhaps not surprising to infer that the most customisable systems are the less formal ones (Table DQ11.a).

The final dimension of PM system customisation that was explored was for people with special needs, disabilities or neurological conditions (for example autism, dyslexia). Only a quarter (26%) of respondents were able to confirm that their PM systems made this specific accommodation; a further third (33%) confirmed that this did not happen, with the largest group of respondents (41%) not knowing either way (Figure 23, Table DQ10).

Encouragingly, more than half of all respondents (63%) agreed that the PM system in their organisation was ‘a fair way of assessing performance regardless of employees' race, gender, age, and personal characteristics’ – 23% ‘strongly’ agreeing with this statement. However, a third of respondents (34%) ‘neither agreed nor disagreed’, with a residual 4% disagreeing to some degree (Table DQ12).

When these findings are disaggregated by organisation size, disagreement can be seen to disproportionately characterise responses from panellists based at medium and large-sized organisations, 7% and 12% of whom respectively disagreed that their PM systems were a fair way of assessing performance irrespective of personal characteristics (Figure 24, Table DQ12.a).

This compares to 4% of respondents from micro-sized organisations and just 2% of those from small organisations. Whether these differences indicate that smaller organisations have fairer PM systems, or simply that their managers are less prone to identify unfairness, cannot be determined.

However, data from the deliberative workshops arguably supports the latter explanation. It must similarly be noted that respondents’ perceptions may differ from the reality of how effectively PM systems are implemented in practice, and may not reflect the views of those employees who experience a greater rate of unfair treatment.

The picture regarding PM system fairness remained mixed when respondents were asked how the performance management process is governed to ensure fair operation. Here, only a quarter of respondents reported that this was done by using HR controls (25%); more than a third (34%) did so through moderations or consistency-checking meetings and an equivalent proportion (34%) said that they ensured fair operation of the PM system via ‘data monitoring processes’ (Table DQ13).

There was a significant association between having a ‘highly formalised’ PM system and using HR controls to ensure fair operation of the PM system; 61% of respondents from highly formalised organisations used HR controls (Table DQ13.a). Conversely, the remaining respondents used other processes such as data monitoring or moderation. It may be that by using centralised HR controls organisations negate to some degree the need to also use these other mechanisms.

A line can perhaps be traced between the findings reported in this section – which show only limited scope for customisation of PM systems for specific staff and variable use of processes to govern their fair operation – and those illustrated in section 2.6, where respondents voiced their desire for more personalised and fairer PM systems.

3. Deliberative workshop findings

During the 1-day deliberative workshop event held near Birmingham in spring 2018, participants were invited to discuss a variety of topics related to performance management (PM) systems. The first session focused on some of the theoretical elements of PM systems, including their purpose, the principles around which a PM system should be designed, and the key practical components of a successful PM system. The event looked extensively at what was driving these behaviours and experiences.

3.1 Key features of group composition

The deliberative event involved participants being divided into 7 groups, which they remained in throughout the day (approximately 3 to 6 participants in most groups). In order to balance the need to have diversity in each group with sufficient homogeneity, to encourage dialogue and facilitate comparisons across groups, participants were split across 3 primary sampling criteria:

- broad industrial sector (public, private, voluntary)

- organisation size (large organisations with 250 staff or more, or voluntary sector organisations with over £100,000 annual turnover; small and medium enterprises with fewer than 250 staff, or voluntary sector organisations with less than £100,00 annual turnover)

- ‘type’ of performance management system

For the last of these criteria, participants were recruited and assigned a sampling status of ‘formal or appraisal-based’ or 'less formal or non-appraisal based’ based on self-classification as follows.

Formal or appraisal-based

The organisation uses traditional end of year performance appraisals or performance reviews as a performance management tool, for presenting feedback to employees on how they are performing against a series of objectives for the year.

Less formal or non-appraisal based

The organisation does not currently use traditional end of year performance appraisals or performance reviews as a performance management tool for presenting feedback to employees on how they are performing against a series of objectives for the year.

However, it must be noted that some participants who associated with ‘less formal or non-appraisal based’ systems in the deliberative workshop groups nevertheless presented using systems that bore many formal features. A degree of formality seems to characterise even the ‘least formal’ systems, with participants acknowledging the use of some formalised processes in these ‘least formal’ systems. It is important to acknowledge that participants self-classified their performance management systems, and that these classifications are subjective and based on their own understanding of the differences between ‘formal’ and ‘less’ formal systems.

There were 7 focus groups in total, reported within the following 6 categories:

- large, private sector organisations, with a formal or appraised-based PM system

- large, private sector organisations with less formal or non-appraisal based PM systems

- small, private sector organisations with a formal or appraised-based PM system

- small, private sector organisations with less formal or non-appraised based PM systems

- large, public sector organisations with a formal or appraisal-based PM system

- small, public sector organisations, and voluntary sector organisations (no differentiation by type of PM system)

It is important to note that these focus group findings differ from the survey findings to varying degrees. This is due to the different research methodologies used and the purposive sampling of participants for the focus groups. Event participants, who tended to be senior HR staff responsible for setting up and implementing the PM systems in their organisations, were selected primarily on the characteristics of the organisations that they work for (size, sector, and type of PM systems used).

They were sampled in modest numbers and qualitative methods were used to gain an understanding of their underlying opinions and motivations. Conversely, survey participants were pre-profiled panellists who were identified as working in HR or as a manager or higher in their company.

They were sampled in far larger numbers, in order to produce numeric results to be generalised from and hence generate insight on the prevalence of attitudes and behaviours. It follows that participants in the focus groups, who were invited to deliberate on these issues in far greater detail and complexity, will have voiced different perspectives and experiences from the survey participants, and this difference in methodology may lead to some areas of divergence in findings.

3.2 The foundations of performance management systems

3.2.1 The purpose of a PM system

Individuals working in large, private sector organisations with formal or appraisal-based PM systems presented many different – but often related – purposes of a PM system, including:

- motivating employees and supporting them to understand their role within an organisation

- recognising success and sharing praise for employees through one to one meetings and coaching sessions between managers and staff

- identifying and monitoring employees’ goals and targets, including developing KPIs related to the individual’s role, and broader targets aligned with company values

- creating and recording an 'audit trail' of staff achievements or against these targets – these records could then feed into discussions of promotions if successful, or disciplinary processes if required at a later stage

Performance management systems were also identified as a method for differentiating between employees. While this was not a universally agreed purpose across participants, many organisations reported using information from the PM system to award performance-related pay such as bonuses. Interestingly, this was not commonly identified as being a primary purpose in the survey. Some survey respondents reported that performance-related pay was a secondary purpose of their PM system: for example, using the PM system to identify areas of success for the employee, which might then be used as examples to award performance-related pay.

In the workshop, using a formal PM system to determine performance-related pay was seen as beneficial for employees. Employees felt that this was fair. The system was also seen as protecting the company if grievances were raised by employees who were unhappy with their rewards, by offering evidence from the PM system as a rationale for the reward.

"So many grievances get back, raised, saying, 'Well, I didn't get this amount of money because the wording in this objective was X, Y and Z, and I did this but the wording was this.' So that […] documentation [in the PM system] becomes even more important with that." (Large, private, formal or appraisal-based PM system)

This was linked by participants to another purpose of using a formal PM system, which was to ensure that employees are measured in the same standardised way; this was of particular relevance when a business had multiple sites or offices, since it demonstrated to employees that rewards or ratings were based on an objective system, rather than individual manager opinion. The final purpose of a PM system was to identify any training or skills gaps across the work force, which was particularly relevant for employees who had been with the company for a long time.

Participants from large, private sector organisations with less formal or non-appraisal based PM systems shared many similar beliefs in the purpose of a PM system. For example, motivating and valuing staff was identified as a key purpose. A PM system should help staff to feel valued and engender positive wellbeing, which in turn would motivate employees to work harder for the organisation.

"It's about listening to the colleague and really sort of getting the most out of them. The manager's got their part to play in making the colleague feel, you know, valued . . . empowered to make decisions and do stuff." (Large, private, less formal or non-appraisal based PM system)

Here, too, PM systems were seen as a tool for awarding pay and other benefits, with high performers identified through the PM system and rewarded with financial incentives. Evidence from the PM system could also be used for national moderation, a process whereby all employees are rated against one another to ensure that ratings are fairly awarded.

The PM system could also be used to determine promotion or demotion within a company, whether this was vertical or horizontal progression. This differentiation was only possible through setting objectives and monitoring performance against them; this would be achieved through regular meetings with staff throughout the year. These meetings could reinforce both individual and business level objectives:

"People's minds wander […] unless you've got that relationship or regular catch up, you know, people can go off in a different direction perhaps and lose the focus of what the business want. You know, if there's objectives coming down from the top, and they're watered down then we'll point [it] out." (Large, private, less formal or non-appraisal based PM system)

Finally, this group felt that identifying skills gaps in the organisation was another key purpose of the PM system. Staff who wanted or need mentorship and coaching could be identified and supported through the PM system.

For participants from small, private sector organisations with a formal or appraisal-based PM system, one key purpose of the PM system was the development of training programmes and identification of skills gaps across the business. PM systems could support the creation and documentation of performance development plans, which would identify what employees could do to progress, including the creation of opportunities for shadowing, coaching and mentoring. These records could also be used to support moving staff into more suitable positions if they were unable to develop in their current role.

PM systems could also be used to engage staff with their own development. This group felt that development of employees was the responsibility of both managers and staff, and that a PM system could be used to encourage ‘buy-in’ from staff into this process.

"[It’s] gotta be a 2-way process, otherwise if they're been done to and they're not gonna take any ownership at all." (Small, private, formal or appraisal-based PM system)

However, this group also felt that a PM system should help employers to manage employee retention and dismissals. The PM system was identified as a tool which provided a record of employee performance through formal documentation, such as performance improvement plans. This helped these organisations to track performance over time and identify individuals who either need support or else may be ‘managed out’ of the organisation.

"It's about deadwood in your organisation, so people that have been there a long, long time and you will try to maybe manage them out of the business, so [having] a PM system properly in place and structured can help that." (Small, private, formal or appraisal-based PM system)

The PM system could identify individuals who were underperforming and who therefore could be made redundant, but also protect the business against claims of unfair dismissal in these instances, using the documents and records from a PM system as evidence of reasoning.

The PM system was therefore a tool of engagement and feedback, which could be used to encourage employees to take control of their development, whilst also being a mechanism for documenting processes among less engaged or low performing individuals leading to dismissal.

Individuals from small private sector organisations with less formal or non-appraisal based PM systems felt that a PM system should be used to develop relationships between staff and employers. For this group, the purpose of the PM system was to help staff learn more about – and support them in – their current role; eventually helping them to progress through the organisation.

This group was also concerned that individual staff circumstances, such as illness or caring responsibilities, could be accounted for within the PM system, ensuring that staff needs were heard by the employer. A PM system was present to boost staff morale, so staff felt that they had time to address issues – personal or work-related – with their managers. This benefited the company as well as the employee, as 'happy staff work better'.

"[In] my performance reviews, we go through personal issues, so things that they might not have to discuss in front of the team, they might discuss and that might be affecting their morale if they've got some other issues somewhere else." (Small, private, less formal or non-appraisal based PM system)

This group identified career development and talent management as a key purpose of the system. Individual staff can develop, and business productivity and profitability can be improved.

"Somebody could be actually sat in the wrong position that's not right for them […] and it's about identifying that […] the position is not right for them or their needs or development training." (Small, private, less formal or non-appraisal based PM system)

This group also highlighted also several benefits for the employer. For example, use of a PM system could strengthen discipline within the organisation, by providing a structure for disciplinary processes and ensuring that evidence of poor performance could be captured. A PM system was a reminder to employees of their duties and responsibilities throughout the course of the year.

"We find, as long as it's regular meetings, they know you're on the ball, you're watching and it's a polite, you know, this needs to be done." (Small, private, less formal or non-appraisal based PM system)

Finally, there was a focus on using the PM system as a structure to ensure compliance with company values and policies. This communicated expectations for employees internally, while signalling to external clients that adequate procedures and policies were in place to address relevant issues. Individuals from large, public sector organisations with formal or appraisal-based PM systems saw the purpose of a PM system as being a mechanism for promoting organisational unity in several areas: signalling company values; supporting staff development; and communicating overall business objectives to employees.

The PM system could monitor the behaviour of employees, as well as their achievements, by tracking both whether targets were met and the methods by which results were achieved. This focus on behaviours also promoted organisational values – such as diversity and inclusion – and therefore acted as a motivational tool for employees as well. Staff may have felt more included and supported by the organisation, and this support may be treated as an intangible benefit for employees in this sector.

"You might've achieved your target - a big tick, a pay rise but actually the […] collateral damage in that process has cost the business elsewhere. So […] the sort of way in which we behave as well as what we achieve is also really important." (Large, public, formal or appraisal-based PM system)

"[My organisation] might not be able to say, 'Well we, you know what, we're not gonna give you a 10% pay rise year on year,' so you stress the other aspects of what's on offer. Which, you know, flexible working [...] the culture […] of respecting difference, etc." (Large, public, formal or appraisal-based PM system)

Another purpose of the PM system as conceived here is to support staff development, considered an important benefit amongst public sector participants. A PM system could therefore be a benefit that supports recruitment and retention in this sector, ensuring that employees feel supported and developed in their workplace, and in touch with their organisation’s values. There were also further benefits to the organisation: by identifying staff skills, the organisation can make better use of their employees, while providing training to further develop staff in ways which benefit the organisation’s requirements.

Lastly, the purpose of a PM system for these organisations was to ensure that that employees are united in their shared understanding of how their work fits together to deliver the organisation’s objectives. The use of a centralised system to manage employees allows for a standardised and transparent measurement of performance to be established in the organisation.

This was identified as a priority by the group, since it allowed skills gaps to be identified at an overall organisation level (as well as communal strengths). Therefore, a formal / appraisal-based PM system promoted an integrated approach to performance management which the group felt ensured a sense of ‘working together’ and cohesion within an organisation.

"These teams might in isolation be working really well but are they actually integrated horizontally to make sure […] that one isn't conflicting with the other […] I think it's the role of the PM system to ensure that […] those links are there." (Large, public, formal or appraisal-based PM system)

The final group, consisting of participants representing small, third-sector organisations and small, public sector organisations, felt that one purpose of a PM system was to ensure that HR teams worked to organisational policies and practices, in order to minimise the occurrence and escalation of disputes initiated by employees raising grievances at work. A PM system supports employers with these difficulties in 2 ways: first, by ensuring that appropriate processes and policies are followed at work, therefore reducing the chance of problems occurring; and second, stipulating the correct next steps to take, if or when these complaints or grievances are reported:

"The performance management is important to stop disputes between employees and employers […if] there isn't a framework, then you know, the last process of that would be employment tribunal." (Small, third-sector and public sector)

There was also a focus on motivating staff using the PM system, by recognising and rewarding good performance, as well as monitoring bad performance. This helped staff to feel valued and supported, and could encourage ongoing shared learning.

"I try to make it a norm that […] we look at problems together, we share problems, and […] we'll take learning points from meetings, if this happened, how could we have done that better, and you know, so it's like a continuous learning thing." (Small, third-sector and public)

Here, PM systems were said to act as a tool to support dialogue between employers and employees, helping to identify areas for support as part of an ongoing process:

"It's not just about basically having a setting objectives and waiting 6 months and reviewing, it's an ongoing review process where that there needs to be dialogue with the employee and the employer on a regular basis […] so that obviously where things are not going [well] then training support and stuff can be put into place and changes can be made to help achieve the overall objective." (Small, third-sector and public)