Executive summary

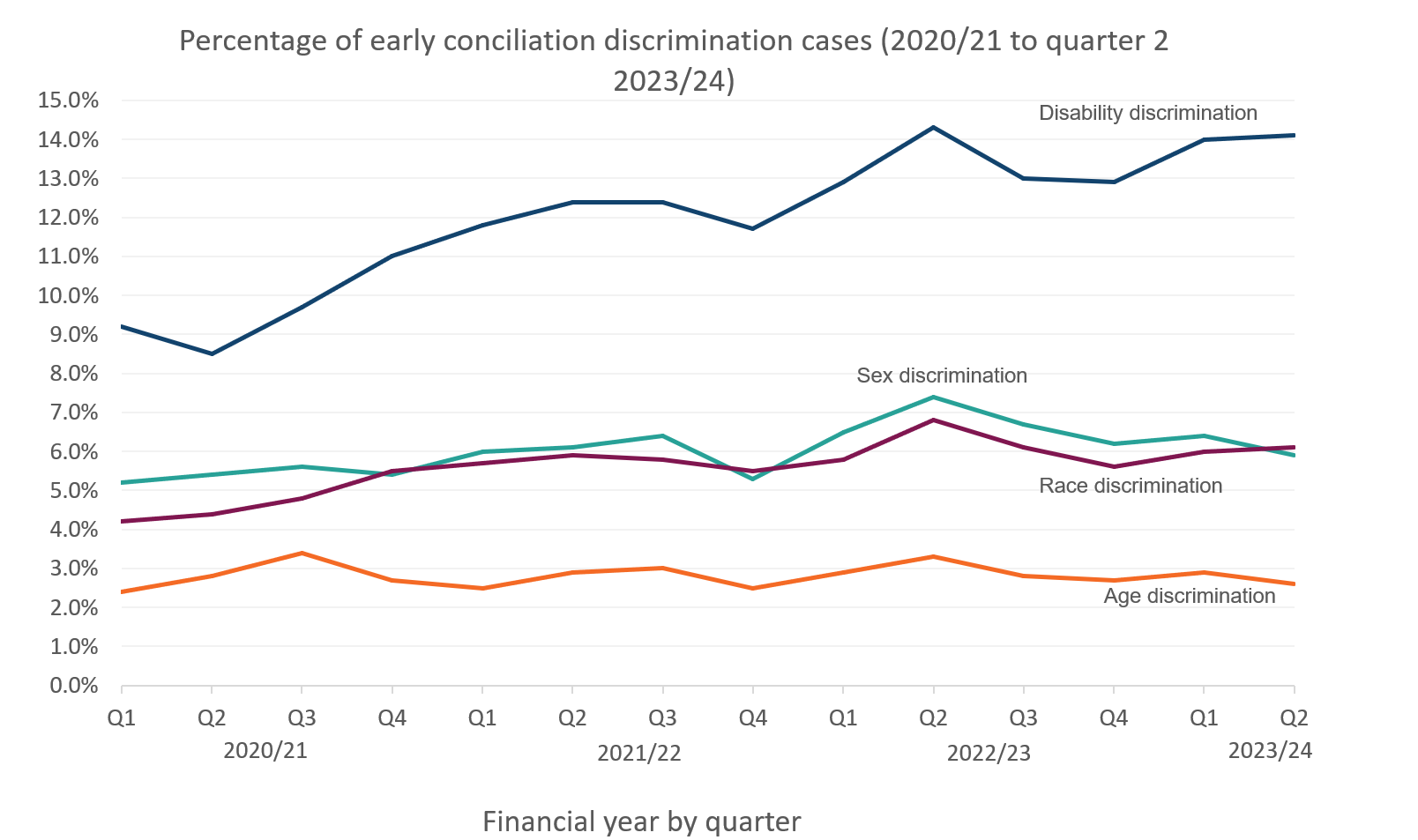

In recent years there has been an increase in the number of disability discrimination claims brought before employment tribunals. This report presents the findings from qualitative research exploring the characteristics and drivers of disability discrimination claims, to understand what might be driving this trend and why some of these claims are not being settled through Acas conciliation. As part of its duty to try to bring about a settlement in employment disputes, Acas offers 2 stages of conciliation: early conciliation, which takes place before the tribunal claim has started, and conciliation in any subsequent tribunal application, that is after the claim has been submitted but before the case has gone before the tribunal hearing.

The research consisted of 33 in-depth interviews: 21 with claimants and 12 with employers who had been party to a disability discrimination claim that was closed between July and December 2023. Participants were selected based on whether they had settled at tribunal conciliation (number=20) or gone to a full tribunal hearing (number=13). All the participants had progressed at least to the point of a tribunal claim being submitted; and they either did not take part in early conciliation, or else participated but reached an impasse at early conciliation. No interviews were carried out with employers and claimants from the same case, and all participants had represented themselves in the claim they were party to.

What are the circumstances giving rise to disability discrimination claims?

There were a range of health conditions and disabilities represented in the sample, and some participants had multiple health conditions. There were 4 main types:

- physical health conditions or impairments, such as visual or mobility impairments or chronic health conditions

- mental health conditions, such as anxiety or depression

- cognitive impairments, relating to processing information

- forms of neurodivergence such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and dyspraxia

It was not always possible from the interviews to determine the legally defined type of discrimination claimants alleged they had experienced, but examples occurred at all stages of the employment journey. This included reported discrimination at the point of recruitment, during employment, or at the end of the employment, for example during dismissal.

Across the sample, there were examples of disability discrimination claims being brought as the sole jurisdiction and under multiple jurisdictions, such as unfair dismissal alongside disability discrimination. In the latter case, some employers perceived that disability discrimination had been added on to the original claim to strengthen it. This perception could then shape how the employer responded.

How do employers handle disability discrimination complaints?

Attempts at internal resolution of disputes between the employer and employee failed where:

- there was a mismatch between the employer and claimant view of the underlying issues to the dispute, with the employer believing that poor performance or persistent absence was the issue, while the claimant felt the dispute related to their disability

- there were disputes about whether suitable reasonable adjustments had been put in place

- the employment relationship had completely broken down and the claimant lacked confidence in the employer's procedures for handling the matter internally

Overall, larger employers that were able to draw on experienced HR or legal departments felt more confident handling disability discrimination claims, especially where they had experienced them before. Smaller employers found it harder to stay on top of best practice, particularly with respect to managing disability issues in the workplace. Overall, claimants had relatively less knowledge about what constituted disability discrimination and were less able to assess the strength of the claim, and so would sometimes seek outside advice and support, for example from third sector advice or support organisations.

What are the drivers that lead to disability discrimination claims reaching an employment tribunal hearing?

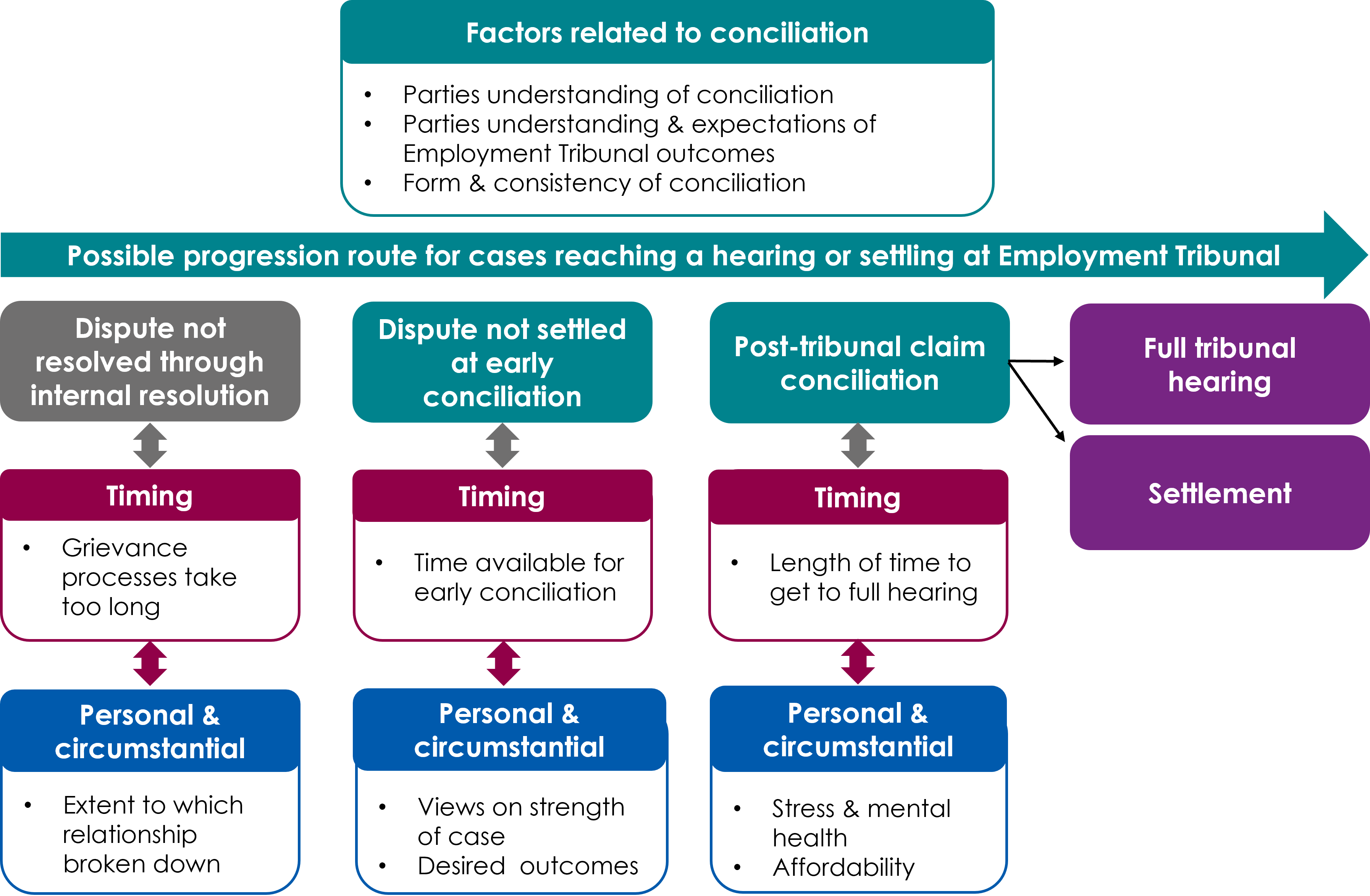

There were several factors that could either drive a claim forward towards a tribunal hearing, or else lead to compromise or settlement. These factors operated at both early conciliation and the subsequent post-claim conciliation stages but came into play in different ways. These are illustrated in figure 2.

Some of these factors are outside of Acas's direct control, while others relate to the conciliation offer and are ones that Acas could shape. Factors that are outside Acas's control included:

- Timing issues: the strict time limits for making a tribunal claim (3 months minus 1 day in most cases) could act as a driver to proceed to a hearing, notwithstanding the provisions for early conciliation to 'stop the clock' on this deadline. Some claimants and employers felt that the 6-week maximum period for early conciliation was not long enough for meaningful engagement, particularly where a claimant's health fluctuated or deteriorated at the time of the claim, suggesting there would be more opportunity to settle were it longer. In contrast, the lengthy period between the submission of the tribunal claim and its eventual hearing could lead people to settle where new information emerged in this interval, their personal circumstances changed or where they simply wanted to get the process over with.

- Personal and circumstantial factors could also come into play, either in driving the case forward or in pushing towards settlement. For example, a decline in health or effects of ongoing stress could lead to claimants settling. In contrast, a strong sense of injustice could drive people towards a full hearing. For employers, the risk of financial and reputational costs could act as a factor supporting compromise and settlement.

In contrast, there are several factors related to the conciliation process that Acas may be able to influence:

- Parties' knowledge and understanding of conciliation and tribunal processes. The findings showed that some claimants and employers had limited understanding of what conciliation was and what it could achieve, meaning they were less likely to engage with it. Information was sometimes provided to claimants in formats that did not account for their disability and which they struggled to engage with. This included written information that was difficult for dyslexic people to engage with, or conversations that people with autism or ADHD found difficult without advance knowledge of topics of discussion.

- Parties' understanding of disability discrimination and expectations of the likely case outcome. Similarly, some claimants had unrealistic expectations of what the outcome of a full hearing might be (for example, in terms of the amount of compensation or ability to be reinstated in their role), or an unrealistic understanding of the strength of their claim and therefore an expectation they would win at tribunal. This was further reinforced where they could not find information to help them assess these issues, either on the Acas website or elsewhere. Claimants and employers said they found information dispersed across different websites, and sometimes fragmented, making it harder to use.

- Nature and consistency of conciliation. While there were examples of conciliators taking a proactive approach to resolving the case, some participants felt that the conciliation service had not supported them to come to an earlier resolution. This was because they felt communication had been too slow; the conciliation process did not help parties understand each other's positions; or the service did not offer enough signposting or advice (for example, on what constitutes disability discrimination, the nature of reasonable adjustments, and to aid assessment of the strength of a claim). Some claimants said they had found contact with Acas conciliators to be frustrating, because it did not give them the help and support they needed. However, service users sometimes had expectations beyond what the conciliation service can offer.

How can Acas improve handling of disability discrimination cases?

Based on these factors, participants made suggestions for how Acas could improve conciliation to support faster resolution of disability discrimination cases.

Improved communication to support understanding of the conciliation offer, including more tailored communication with disabled people and those experiencing ill-health. Some claimants described receiving written or oral information that was inaccessible to them due to their disability, and it was a clear that some participants lacked a clear understanding of what conciliation meant.

More regular and proactive contact with customers. At both early and later stages of conciliation, employers and claimants wanted conciliators to be more proactive in persuading both parties about the benefits of taking part in conciliation and bringing their positions closer together. For claimants who may be struggling with their mental health, having conciliators be more proactive and take responsibility for maintaining contact would have helped.

Improvements in the signposting of information, especially signposting to information that would allow customers to assess the strength of their case, suitable levels of compensation, and evidence of the benefits of earlier settlement would support earlier resolution. Without this kind of signposting, claimants could not see how Acas added value in helping them decide whether to settle or proceed to a hearing.

What else could Acas do to support faster resolution of disability discrimination cases?

Better direction to written advisory content for employers, employees and claimants is highlighted as an area where Acas could add value. In particular, information about reasonable adjustments, best practice in managing disability and performance, and summaries of relevant case law would all support better handling of disability discrimination cases. The fact that Acas already provides a wide range of written advice on many of these and other topics highlights the importance of when and how this type of advice is shared and the form this takes.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of qualitative research to understand the reasons behind the increasing number of disability discrimination claims proceeding to employment tribunal (see separate Appendices, section A). Data from both Acas and the employment tribunal show that there has been a recent rise in the number of cases of disability discrimination reaching tribunal. In this context, Acas commissioned the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) to undertake research to understand why this rise in disability discrimination cases has occurred, and what they can do to try to resolve disability discrimination cases earlier, more quickly and more cost-effectively through conciliation.

1.1 The stages of conciliation

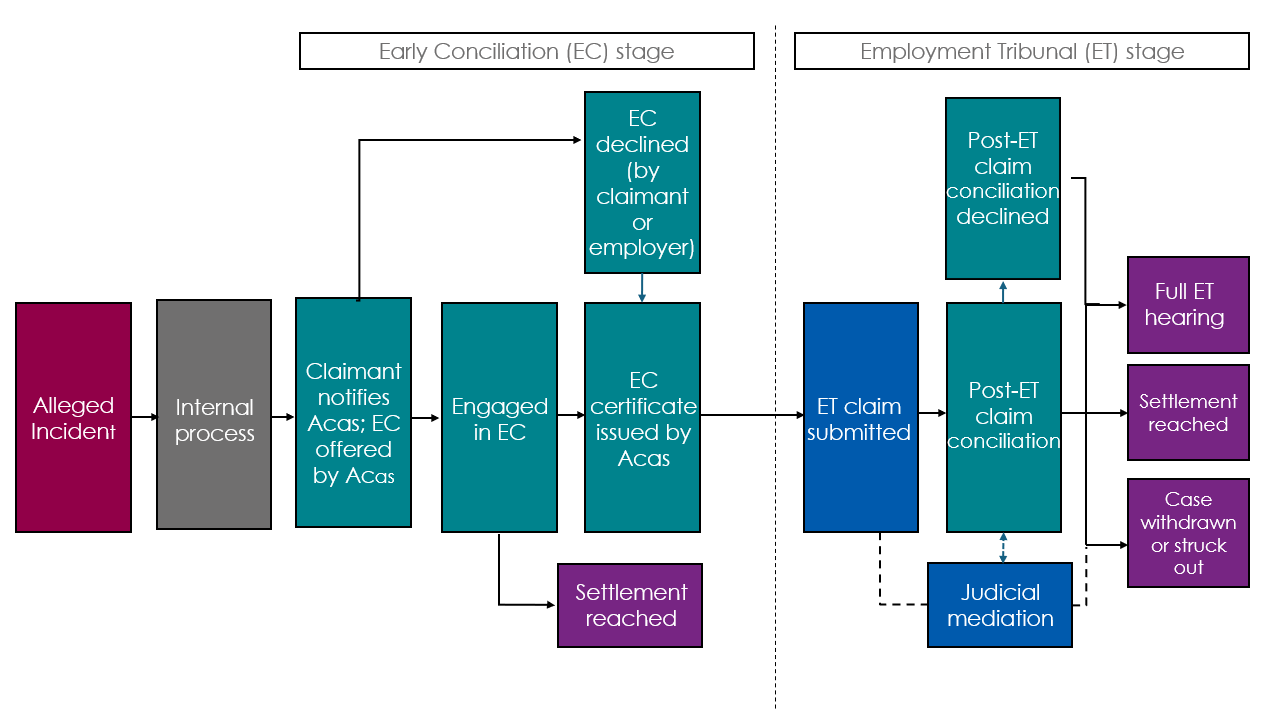

Acas has a duty to promote a settlement between the 2 parties who are subject to an employment dispute. It provides individual conciliation services that aim to resolve claims and prevent them from reaching tribunal. They do this by facilitating discussions between claimants and employers (or respondents ) to explore whether a resolution can be reached. These include early conciliation, and following submission of the tribunal claim, post-tribunal claim conciliation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows the stages in handling a disability discrimination claim. This has 3 stages:

- Internal process

- The early conciliation stage

- The employment tribunal stage

The internal process stage contains 2 steps:

- The alleged incident

- The internal process

The early conciliation stage contains 3 steps:

- Claimant notifies Acas and is offered early conciliation, employee or employer can decline

- If both parties agree, they engage in early conciliation

- Settlement or early conciliation certificate issued by Acas

If settlement is not reached the dispute will progress to the employment tribunal stage. At this stage the tribunal claim is submitted and post-tribunal conciliation is offered to both parties. This can result in:

- Post-tribunal conciliation being declined

- Settlement being reached

Judicial mediation may be offered during the employment tribunal stage.

If no settlement is reached or conciliation is declined, there may be a full hearing or the case is withdrawn or struck out.

It is mandatory for employees wishing to lodge a disability discrimination tribunal claim to notify Acas first in most cases. This prompts Acas to offer early conciliation – a process whereby conciliated talks between employees and employers seek to resolve the dispute instead of it progressing to an employment tribunal. These talks take place for up to 6 weeks, during which time the deadline for submission of the tribunal claim is paused. Early conciliation is offered first to the claimant, who can accept or decline. If accepted, the employer can choose whether to engage or not. Where either party declines to take part in early conciliation, or if the talks reach an impasse, the claimant is issued with an early conciliation certificate, which allows them to proceed to make a claim to an employment tribunal, in most cases within 1 month.

Conciliation is offered again by Acas after the tribunal claim has been lodged by the claimant. As at early conciliation, conciliation here involves facilitating messaging between parties and helping write-up any ensuing settlement agreements. Post-tribunal claim conciliation can take place at any point up to the tribunal hearing, the wait time for which can be many months. As at early conciliation, participation remains voluntary. If a settlement is not reached, the case proceeds to the tribunal hearing, where the outcome is decided by the tribunal panel of employment judges.

1.2 Research questions

The research aims to explore the characteristics and drivers of the disability discrimination caseload, including how Acas might improve its conciliation services and advisory content to help resolve claims earlier. The research aims and sub questions were:

Aim 1: To better understand the reasons why disability discrimination claims that go to an employment tribunal are not resolved at the earlier early conciliation or tribunal conciliation stages.

- What are the circumstances giving rise to disability discrimination claims?

- How do employers handle disability discrimination claims, and does this differ compared to other forms of alleged discrimination? How knowledgeable are employers about disability discrimination and their legal responsibilities?

- What are the drivers that lead to disability discrimination claims reaching a tribunal hearing?

Aim 2: To explore how Acas can positively influence the incidence and outcome of tribunal claims, through advice and conciliation.

- How can Acas improve conciliation handling of disability discrimination claims?

- What else could Acas do to support faster and earlier resolution of disability discrimination claims?

1.3 Methodology

This research consisted of 33 in-depth telephone or online interviews, including 21 with claimants and 12 with employers who were party to a disability discrimination claim that was closed between July and December 2023. The sample was drawn from Acas's management system, with Acas running an opt-out process. The sample only included unrepresented claimants and employers who had not settled during early conciliation, either because they did take part in early conciliation, or they reached an impasse.

The research used a purposive sampling approach, selecting participants based on whether they settled during post-tribunal claim conciliation (20) or proceeded to a full tribunal hearing (13). No interviews were carried out with employers and claimants party to the same claim. Other secondary criteria were also monitored to achieve diversity across the sample, including size and sector of employer; and whether the case involved single or multiple case jurisdictions. Further details about recruitment and the achieved sample are shown in the separate Appendices, section B.

Interviews lasted between 45 to 60 minutes and were conducted using a topic guide agreed with Acas (see separate appendices, section C). The interviews covered participants' journeys from the time an alleged incident of disability discrimination first arose, through their experiences of Acas conciliation, and their decisions about whether to try to resolve a claim at different stages in the process. In some cases, interviews were challenging because the topic was still very emotive for participants. Interviews were also rescheduled and adapted to reflect participants' health conditions.

All interviews were audio recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim. They were analysed using NatCen Framework approach, which uses case and theme-based analysis, while also ensuring findings are grounded fully in the data.

This report does not provide numerical findings, since qualitative research does not support statistical analysis. Instead, purposive sampling seeks to show range and diversity of experiences among research participants. Qualitative findings, therefore, provide in-depth insights into the range of views and experiences in the study. Verbatim quotes or case illustrations are used throughout the report to illustrate these views and experiences where pertinent.

1.4 Structure of the report

The report is divided into the following sections:

- Chapter 2 addresses research questions 1 and 2, describing the characteristics and natures of disability discrimination claims and exploring how employers respond

- Chapter 3 addresses research question 3, and centres on understanding the journeys of disability discrimination claims

- Chapter 4 addresses research questions 4 and 5, exploring participants' views on how Acas's conciliation services could be improved in the future, with a view to prevent more cases escalating to an employment tribunal

2. The nature of workplace disability discrimination cases, and how are they being handled by employers

This chapter explores the characteristics and nature of disability discrimination claims. This includes the types of health conditions included in the sample and the types of issues giving rise to claims. The interaction of disability discrimination with other jurisdictions, such as unfair dismissal or breach of contract is also discussed. This chapter also discusses how employers handled claims and tried to resolve them internally and why these attempts were not successful.

2.1 What are the nature and characteristics of disability discrimination claims?

2.1.1. What is the range of disability and health conditions at issue in disability discrimination claims?

The disabilities and health conditions discussed by participants in interviews fell into 4 categories:

- Physical disabilities and health conditions, such as speech impairments, visual impairments, mobility issues, and having a colostomy bag or stoma. Specific disabilities and health conditions included cerebral palsy, chronic fatigue syndrome, epilepsy, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), sickle cell anaemia, skin allergies and conditions, and spina bifida

- Mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and psychosis

- Cognitive impairments, related to issues processing information

- Forms of neurodivergence, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, dyslexia, and dyspraxia

Some of the participants had multiple disabilities and health conditions, which interacted making their experiences of disability discrimination more complex, for example, a participant whose condition affected their movement and mobility, who was also dyslexic.

2.1.2. How do disability discrimination claims interact with other jurisdictions?

While some participants gave accounts of disability discrimination as the sole jurisdiction of their tribunal claim, others described claims they had brought under multiple jurisdictions – that is, involving other matters of employment law in addition to disability discrimination. These other jurisdictions included unfair dismissal, failure to allow statutory rest breaks, denial of flexible working requests, breach of contract, unpaid wages, and being victimised for trade union membership. Disability discrimination therefore interacted with these other jurisdictions in a range of ways, from being the primary reason for the claim, to being perceived as being added to one or more other jurisdictions.

3 patterns of claims were found:

- Disability discrimination as the sole jurisdiction. In these cases, disability discrimination was clearly the focus of the claim. For example, having a job offer withdrawn after disclosing a disability.

- Disability discrimination was not the initial focus of the claim but arose from the handling of the original claim. Sometimes poor handling by the employer or line manager of an initial claim that was not directly related to disability – for example, a request for flexible working to manage fluctuating mental health led to other conditions (anxiety and stress) being triggered or exacerbated by not being able to sometimes work from home, with other aspects of the claimant's health becoming part of the claim.

- Disability discrimination was added to other jurisdiction(s) at the outset of the claim. Here disability was presented by the claimant alongside one or more other issues, such as unfair dismissal – employers perceived such cases as having involved issues such as poor performance, excessive sickness absence, bad behaviour, poor discipline, or breach of contract. In some of these cases, employers suspected that a disability or health condition was only raised as a supplementary part of the claim at the point of the employee being dismissed, disciplined, or resigning. Some claimants said they were told a by a solicitor or support organisation to add disability discrimination to other jurisdictions. This was because the solicitor believed there may be a case of disability discrimination for the employer to answer, and that doing so would strengthen the claimant's case.

Notably, we did not find significant interaction between disability discrimination and other protected characteristics. However, some participants mentioned pregnancy, race, sex, and sexual orientation as another, unrelated part of their claim.

2.1.3. What types of issues are giving rise to disability discrimination claims?

Although it was not possible to tell from the interviews how each case may have been categorised under the Equality Act (2010), there were instances that were likely to be considered direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, harassment, and victimisation. Issues tended to be linked to disagreements over what constituted reasonable adjustments; the management of sickness absences related to disability; and subsequent complaints, resignations, or dismissals.

The alleged incidents arose at different stages in employment. They occurred at the point of recruitment, during employment, and during investigations of alleged discrimination before or after dismissal:

During or after recruitment. Claimants cited examples where recruiters or employers failed to make reasonable adjustments to allow them to complete job applications verbally or carry out a job interview in an accessible way, such as through typing.

In one case, a claimant said an employer had withdrawn a job offer after finding out they were a wheelchair user. This was on the grounds that the employer determined they would not be able to do the job in a wheelchair.

During employment. Here, claimants reported that disability discrimination issues had arisen due to disagreements about reasonable adjustments, or where they felt harassed into returning to work too quickly after a period of sickness absence.

In some cases, claimants said their employer had refused to make reasonable adjustments because they did not see them as 'reasonable' or sufficiently connected to their job. For example, a claimant with ADHD explained that their employer did not agree that they needed more time to adjust to a new call handling system to prevent them making mistakes. Where reasonable adjustments were agreed, claimants felt employers were sometimes slow to implement them, or needed to be constantly reminded that they were not yet in place.

Change of management could also lead to disability discrimination claims during employment. Claimants described how differing attitudes of employers or line managers to existing reasonable adjustments meant that a change of manager could lead to previously agreement adjustments being withdrawn. For example, in one instance a change in manager meant that previously agreed hybrid working arrangements were removed.

Some claimants said that they were harassed by employers when they were signed off work by a doctor on grounds of stress or poor mental health (with this sometimes arising from what claimants saw as a failure to make reasonable adjustments in the first place).

This could also lead to a feeling the claimant was being targeted or victimised with the aim of constructively dismissing them.

In handling a complaint, grievance, and dismissal. Claimants described situations in which the employer had not followed correct procedures in terms of managing absence due to sickness or reasonable adjustments. There were examples of people having been dismissed whilst they were suspended from work due to health concerns or being dismissed without the employer having first responded to a grievance they had submitted.

While some employers did make reasonable adjustments or allowed employees to change their role to remove or reduce any issues related to their disability, there were cases where analysis of the interviews suggested that employers probably moved too quickly to dismissal. This emerged in cases where claimants said employers reacted quickly over what their employers saw as too many sickness absences, or a perceived inability of the claimant to perform their role. Some employers simply did not extend a probationary period or did not renewing a short-term contract. By comparison other employers only took this approach after discussing possible reasons for poorer performance, carrying out an occupational health assessment or attempts at redeployment.

2.2 Do employers handle complaints about disability discrimination differently from other types of complaints?

There may be many opportunities for employers and employees to try to resolve a workplace dispute internally – informally, or else following a formal disciplinary and grievance process – before it even reaches the point of an employee notifying Acas about making a claim to an employment tribunal. This section explores how employers handled complaints of disability discrimination internally, whether they understood their responsibilities about making reasonable adjustments, and the impact of the lack of employer and employee knowledge about possible reasonable adjustments.

2.2.1. How knowledgeable are employers and claimants about disability discrimination?

Employers and claimants showed varying levels of knowledge about disability discrimination and good practice on disability in the workplace.

For employers, knowledge about the law on disability discrimination came from previous experience of responding to such claims personally. This included participants who worked in HR departments, organisations' legal representatives, or legal consultants they regularly used. Consequently, their experience and qualifications meant they were more confident in dealing with disability discrimination complaints than were claimants. In some cases, employers described that they had subsequently introduced training for staff on management of disability discrimination following the claim.

The exception to this pattern was smaller organisations without a dedicated HR department or outsourced HR support, who found it harder to keep up with legislation and good practice. This was because they had to juggle the management of the organisation with personnel matters. Where there was a lack of experience, employers relied on following existing procedures, if available, or external advice including from legal consultants or solicitors.

There was also evidence from employers and claimants that knowledge of disability discrimination among HR staff was not being cascaded to line managers. The ensuing lack of knowledge at line managerial level led to disability discrimination cases being mishandled, staff possibly moving too quickly to formal disciplinary action or even dismissal, and making procedural errors in the handling of cases.

Claimants were less likely than employers to have knowledge of disability discrimination from a professional or legal standpoint, and so often sought advice on how to proceed with their case once they felt they had experienced disability discrimination. Sometimes claimants had legal knowledge from previous experiences of disability discrimination, and if they had been to the employment tribunal before and represented themselves. This gave them more confidence in making a claim.

Where claimants did not have much knowledge, they sought advice from trade unions, charitable or voluntary sector organisations, online, and from Acas's helpline. All the claimants in the study represented themselves – this decision was either due to the cost because they were not a trade union member, or when they felt their union was not helpful or unconvinced about the strength of the claim.

Organisations from which claimants sought advice included the Equality Advisory Support Service, Citizens Advice, Pregnant Then Screwed and Valla, an online legal platform designed to offer low cost legal support for people taking out a grievance against their employer or going to an employment tribunal.

Advice from previous claimants was particularly valued, as they had been in the same position. Claimants discussed using online forums, and YouTube channels where they found advice. They praised these organisations and forums for giving them confidence when they were going through the process of questioning their treatment by an employer, and deciding whether they had a strong enough case.Claimants in the study all represented themselves – where they had sought legal advice, it was usually through friends and family who had experience in the legal sector; although there were some instances where claimants paid for advice from a solicitor themselves. Employers thought that solicitors were sometimes the driving force behind claimants' decision to proceed to a full tribunal hearing, even in cases that the employer perceived to be weak, and that the claimant was therefore unlikely to win.

2.2.2. Why are disability discrimination complaints not resolved internally?

There were varying degrees to which employers tried to manage and resolve issues before they reached the stage of the claimant formalising their intention to make an employment tribunal claim. However, disability discrimination claims arose when they could no longer be managed internally. There were several reasons for this, as follows.

There was a disagreement over an employee's capability to perform their role. While claimants alleged disability discrimination, employers sometimes considered that an employee was simply under performing or incapable of doing their job. Both claimants and employers reflected that, as a result, things sometimes moved too quickly to formal processes without exploring informal means to resolve disputes.

Claimants emphasised the way in which their disability or poor health made it harder for them to perform their job. They observed that they were struggling physically or mentally, and sometimes had to take time off sick due to stress, or employers not making reasonable adjustments.

By contrast employers noted examples of persistent sickness absences or poor performance. For example, an employer said:

"Their position is usually, 'I can't help it,' [but] after we've factored in the challenges you have … they've tried to work within those reasonable adjustments, but they just can't either get to work, or … they just can't do it" (Employer 4, private sector, over 250 staff).

Disagreements between employees and employers over the extent to which the latter were obligated to make reasonable adjustments could lead to an impasse. This was especially the case where some employers had tried to make reasonable adjustments, but they felt they had not worked.

There were disputes over whether suitable reasonable adjustments had been put in place. Clearly this can be an area for disputes since what is considered 'reasonable' is subjective and is not clearly defined in law. Claimants reported numerous issues in relation to reasonable adjustments. These included: asking for them but not being given them; employers saying they would discuss them but never doing so; and employers taking a long time to implement the adjustments, or not adhering to them consistently.

Changes in management also meant that reasonable adjustments were sometimes withdrawn, as discussed above. Similarly, a change in line management could also be distressing if a previous line manager had a good understanding of their disability or health condition, and the adjustments they needed, while a new manager did not.

Disagreements led to a breakdown in the employment relationship. Arguments and disagreements with managers over reasonable adjustments, perceived poor performance, or sickness absence, sometimes led to a complete breakdown of working relationships.

In some cases, claimants made a formal grievance against their employer, went off sick, or resigned over disagreements about their disability. They said they felt that their employer did not want to understand their disability and was simply trying to 'get rid of them'. This led to claimants expressing a sense of anger, personal injustice or upset, which resulted in the employer and employee not talking. Claimants did not always have confidence in the internal processes being fair.

These feelings of injustice were sometimes so strong that claimants felt the only way to 'get some closure' was to make a claim of disability discrimination and go to tribunal. This sense of injustice also contributed to claimants' decision-making in pursuing a tribunal claim all the way to full hearing (as discussed further in chapter 3). One claimant said:

"It just didn't sit right with me, what had happened, and I wanted to understand. Is this acceptable, that someone can be made to feel like that?" (Claimant 5, private sector, 50 to 249 staff)

Internal processes could also take so long that they had not concluded by the time the claimant needed to submit the claim. There was a perception among some claimants that they had hit a brick wall in terms of seeking a resolution internally.

By contrast employers thought they had already made enough adjustments to accommodate an employee's disability or ill-health, were tired of the situation, and so moved to disciplining or dismissing them. Since employers often felt the issue was one of poor performance rather than disability discrimination, they considered that they had 'done nothing wrong':

"Well, we can't settle a claim where we don't think we've done anything substantially wrong" (Employer 1, public sector, over 250 staff)

Other employers felt that they had simply exhausted all options of reasonable adjustments available to them. While some conceded that, with hindsight, they could have handled the situation better, they nevertheless felt that, overall, they had done all they could at the time.

Together these factors meant that either or both parties felt that the issues could not be resolved internally or without a third party being involved.

2.2.3. Are claims brought under a single jurisdiction handled differently?

The findings suggest that employers tended to be more comfortable dealing with claims of disability discrimination where they involved a single issue related to disability, and where relatively simple or well-known reasonable adjustments could be made. For example, installing specialist software on computers to support dyslexic employees or offering reduced hours or counselling for employees experiencing periods of poor mental health.

They were less comfortable dealing with more complex issues involving forms of neurodivergence, complex mental health conditions, and conditions leading to extended sickness absences and concerns about work performance. These cases tended to be less well understood and perceived as less clear cut in terms of whether disability discrimination had taken place. They were therefore more likely to result in complaints that required third party involvement.

In addition, employers were sometimes less sympathetic to disability discrimination claims involving other jurisdictions, where they believed disability discrimination had only been brought into the case at a later stage to try to shore up a less substantial claim against having been disciplined or dismissed. In one case, the claim began as disciplinary action for incompetence and the employee was very cooperative. However, once it was decided that the employee would be dismissed, they appealed and raised the issue of their anxiety and depression.

In summary, issues leading to disability discrimination claims tended to be linked to disagreements over what constituted reasonable adjustments; the management of sickness absences related to disability; and subsequent complaints, resignations, or dismissals. Although employers and claimants often tried to resolve these issues internally in the first instance, a lack of knowledge and experience, deteriorating relationships between employer and claimants, and a sense of no wrongdoing on the part of either party could lead to these claims escalating to the point of resolution requiring external input.

3. Factors that affect whether parties settle through conciliation or proceed to tribunal

This chapter covers the factors that led parties to settle claims of disability discrimination through Acas conciliation, or else proceed to a full employment tribunal hearing. It first sets out the different stages in the customer journey where there are opportunities for conciliation and gives an overview of the factors that influenced decisions on whether to proceed to the next stage. It then explores the experiences of unrepresented claimants and employers who went to tribunal, and their degree of satisfaction with the outcomes.

3.1 Where in the customer journey can Acas influence the factors driving disability discrimination claims?

There were numerous factors that either drove claimants or employers on to the next stage in the tribunal process, or that led them to decide to reach a settlement. They were divided into areas in which Acas may have opportunities to intervene, and those where Acas may have potential to influence but not directly control them. Figure 2 below sets out the different stages in the customer journey in making a claim and the key factors that could lead to a settlement or drive participants on to full hearing.

Those areas where Acas may have opportunities to intervene through more direct, proactive conciliation, or the creation of evidence-based, written advisory content, were to do with factors that related to the conciliation process, including:

- Parties' knowledge and understanding of the conciliation and tribunal process. Both claimants and employers did not always understand what conciliation was and what it could achieve, meaning they were less likely to engage with it. This also meant that there could be a mismatch between what claimants and employers expected of conciliation, and what Acas can provide within the current remit.

- Parties' understanding of disability discrimination and expectations of the likely outcome of the tribunal. Similarly, some claimants had unrealistic expectations of what the outcome of their case might be at a hearing, or an unrealistic understanding of the strength of their claim.

- Form and consistency of conciliation services. In some cases, claimants and employers felt that the conciliation service had not supported them to come to an earlier resolution. This was because communication was perceived as being too slow; the conciliation process did not help parties understand each other's positions; or the service did not offer enough signposting or advice to information that would have helped parties decide to settle (for example what kind of reasonable adjustments have been made by employers for types of disability, previous outcomes from tribunals for similar types of claims, how levels of compensation payments are calculated).

Figure 2 shows factors related to conciliation and the possible route for a dispute reaching a hearing or settlement at employment tribunal.

Factors related to conciliation include:

- parties understanding of conciliation

- parties understanding and expectation of employment tribunal outcomes

- form and consistency of conciliation

The route for a dispute reaching hearing or settlement has 3 stages:

- disputes not resolved internally

- disputes not resolved at early conciliation

- disputes at post-tribunal conciliation

The factors that influence a dispute not being resolved internally have been shown to be:

- the grievance procedure taking a long time

- the relationship has broken down

The factors that influence decisions for not resolving at early conciliation have been shown to be:

- time available for conciliation

- views on the strengths of the case

- desired outcomes

The factors influencing decisions for not resolving at post-tribunal claim conciliation have been shown to be:

- length of time to get to full hearing

- stress and mental health

- affordability

After post-tribunal conciliation, the parties can reach a settlement or go to a full tribunal hearing.

Factors where Acas may have less direct control, but some potential to influence, were:

- Timing issues – related to deadlines for making a claim to an employment tribunal (3 months minus 1 day for most claims); the 6-week maximum 'stop the clock' provisions for early conciliation; the length of time it took for cases to reach full a hearing following submission of the claim; and the belated availability of new information pertinent to the case. These issues also interacted with the parties' feelings about the case, their sense of continuing anger or injustice, and whether new information or changes in circumstances changed their minds about whether to proceed to tribunal.

- Personal and circumstantial issues – to do with the degree to which the parties felt legally, financially, and emotionally supported in their case, whether their physical and mental health was good enough to continue, the stress this placed on them and their families, and whether they could risk the financial or reputational costs of losing a case.

All these factors above were important, in one direction or the other, along the customer journey. These are explored in the sections that follow; both in terms of the factors relevant at each stage of conciliation, and the subtle ways in which they interacted to encourage settlement, or to drive parties towards a full hearing at an employment tribunal.

3.2 Why are some claims not being settled at early conciliation?

This section examines the factors that affected whether claimants and employers took part in early conciliation, whether they actively engaged with it, and what shaped their decisions to proceed to the next stage.

3.2.1. What factors affect whether customers take part in early conciliation?

There were 3 main factors that affected whether customers took part in early conciliation:

- the extent to which the relationship between parties had broken down

- whether parties were fully aware of and understood the early conciliation offer

- the length of time in which early conciliation must take place.

These are discussed in turn below.

Summary of the factors shaping whether customers take part in early conciliation:

- Personal and circumstantial factors: the extent to which the relationship between parties had broken down

- Factors related to conciliation: whether parties were fully aware of and understood the early conciliation offer

- Timing issues: The 6-week period in which early conciliation can take place

Breakdown of relationship between the parties. As discussed in chapter 2, there were a variety of reasons why disputes arose between parties, resulting in one or both parties feeling angry and injured, and their relationship breaking down.

Claimants said they declined to use early conciliation where they felt they were not being listened to by the employer, the employer denied any liability in their case, or the parties were simply no longer talking to each other, amicably or at all.

Employers said that, even where they had been willing to take part in early conciliation, the claimant had failed to engage with or else withdrawn from the early conciliation process. However, employers also declined to take part where they felt that they had followed correct procedures or that they had 'done nothing wrong'.

A breakdown in communications could also be a reason for taking part in early conciliation. By taking part, the parties hoped that Acas would act as a 'go between', facilitating communications that might not otherwise have happened. As one claimant put it, Acas acted as an 'iron barrier', which helped reduce angry and emotional contacts. Others liked the fact that the conciliator had acted as a neutral agent when they had previously only encountered hostile communications from their employer and their representatives.

However, taking part in early conciliation for claimants could also be seen as a way of formalising or 'ramping up' communications with their employer thereby forcing their employer to take their claim more seriously.

Lack of awareness or understanding about early conciliation. Some potential users of early conciliation did not participate, either because they appeared to be unaware of having had the option to take part, or because they did not understand what using early conciliation offered them. The term 'conciliation' itself was confusing to some people due to unfamiliarity with it.

Additionally, some claimants and employers appeared to not have fully understood the early conciliation offer or appreciate that they had taken part in it. This possibly related to claimants not being able to engage in communications in certain forms or being unwell at the point of when contact with them was made.

Claimants also said that, when they were most unwell, they would have welcomed their Acas conciliator taking more of the responsibility for establishing and maintaining regular, meaningful contact, instead of it being incumbent upon them to initiate contact with the conciliator (see section 4.1). They therefore saw the conciliator as helping ensure contact and momentum between the parties was maintained, rather the simply passing on communications.

For their part, employers were also sometimes unaware that early conciliation existed and only found out that an employee had made a claim of discrimination against them when they received the tribunal form. This is because early conciliation is only offered to the employer where the claimant first agrees to participate. Some employers said they would have liked to take part in early conciliation if they had been given the option, but subsequently found out the claimant had already declined.

In this context, some employers and claimants thought early conciliation should be compulsory where the other party had declined to take part, or that parties should be more actively encouraged to participate, rather than it being seen as a 'stepping stone' to tribunal. This may include using research to show why claimants and employers sometimes wished they had settled earlier through conciliation rather than going to tribunal.

The length of time in which early conciliation must take place. There are strict time limits for making a claim to an employment tribunal (known as the 'limitation period'). In most cases, claimants have 3 months minus 1 day from the date the problem at work happened. Some claimants felt that this length of time had not been sufficient. Although the limitation period is paused for up to 6 weeks while early conciliation takes place, some claimants said that they nonetheless felt forced into submitting their ET1 tribunal claim form, because their employer had still not responded to an outstanding grievance before the time ran out for early conciliation.

In these cases, claimants sometimes suspected employers were deliberately delaying the process to test their determination to proceed to tribunal. This happened where the claimant had resigned, had been dismissed, or they were on a period of prolonged sickness absence. In contrast, some claimants said they let the period for early conciliation elapse without meaningfully participating because they did not want to disclose information to their employer that might ultimately be used against them at tribunal. This led some participants to argue that 6 weeks was not a long enough period for meaningful engagement and that in some cases only 'a handful' of emails had been exchanged during that time.

3.2.2. What factors shape decisions to proceed with disability discrimination claims?

Here discussion focused on:

- the perception that the other party had not really engaged in early conciliation

- whether employers thought they had a case to answer

- whether the correct policies and procedures had been followed in handling the case

- desired outcomes from the claim (especially desired level of payments)

These are discussed below.

One or other party did not meaningfully engage. Employers and claimants decided to press on to a full hearing when one or both believed that the other showed no willingness to compromise; to try to understand the other's perspective; or show remorse for the dispute having arisen. As one claimant experiencing symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder put it:

"The last place I wanted to go was an employment tribunal, but I had no option because they just wouldn't consider or talk or explain anything to me" (Claimant 15, public sector, over 250 staff).

This meant, that despite both parties agreeing to take part in early conciliation, they reached an impasse.

Employers with 'no case to answer'. A key reason employers decided to press on to full hearing was that they felt that, in terms of disability discrimination, they had 'done nothing wrong'. This view was voiced by employers who felt the dispute was really about something else such as poor performance, absence, or breach of contractual obligation, rather than disability discrimination (see section 2.1.2).

For instance, one employer discussed a case where a person with a visual impairment had been consistently rude and aggressive to other staff. Although there had been a delay in obtaining some specialist equipment to make their work easier as part of a reasonable adjustment, they nevertheless saw the issue as one of discipline, not disability.

While some employers saw such claims as vexatious, others felt it was simply a way for ex-employees to express their frustration and anger over being disciplined or dismissed.

A sense of injustice and 'righting a wrong' among claimants. Claimants, by comparison, tended to see their decision to press on to full hearing as a determination to right a wrong or to correct an injustice. This included alleged disability discrimination during recruitment and employment.

Regarding disability discrimination at recruitment, a claimant with a cognitive impairment said they felt discriminated against because they were told they could not give oral responses for an application form, instead of in writing. They felt confident it was disability discrimination because they researched possible reasonable adjustments during recruitment and had already won a similar case at tribunal before.

Regarding disability discrimination during employment, claimants also expressed a desire to make work better for them and others in the future. They talked about the importance of challenging 'old-fashioned' or 'toxic' working cultures for disabled people.

A sense of 'righting a wrong' could also drive cases where they involved another jurisdiction as well as disability discrimination (for example, failure to give statutory breaks, denial of reasonable flexible working requests). An example was a hotel worker who said they had medical conditions that meant they could not work long hours or multiple days in succession without suitable rest periods.

Whether internal procedures had been followed. Another factor that drove employers and claimants on towards a full hearing was whether they felt the case had been managed well internally.

Sometimes a willingness to take part in early conciliation for claimants was driven by the fact that they had been advised that their employer had not followed a full and fair procedure in line with good practice. In these cases, they had sought advice from third parties such as a solicitor or Citizens Advice, who suggested that their employer had made significant handling or procedural mistakes, for example not giving verbal or written warnings prior to dismissal.

By engaging in early conciliation, these claimants had hoped that the employer would admit to not having handled the process properly. Where this did not happen, it made the claimant more determined to proceed to the full tribunal hearing.

From the opposite perspective, employers could be equally confident that they had followed correct procedures, and therefore would not back down. This was especially the case where they had: (a) put in place reasonable adjustments but judged that employee performance had not improved; or (b) had conducted an occupational health assessment to assess whether the employee was still capable of their job or suitable for redeployment, but found the employee was not. Good management of issues related to disability in this respect usually involved skilled HR professionals, employers with their own solicitors, or advice from specialist legal consultants.

However, even in some cases where employers admitted procedural errors, they sometimes refused to settle because they thought the claimant's request for an apology or to be reinstated in their job was unreasonable, or that they were asking for an excessive payment.

Level of compensation payments. A significant reason why the parties failed to settle at early conciliation was linked to the amount of money requested or offered for settlement. Claimants sometimes said that the amount of money offered was 'insulting' or 'derogatory', particularly where they were only offered outstanding pay at the point of resignation or dismissal, or where they felt that had a clear case of discrimination. Employers said claimants could have completely 'unrealistic expectations', sometimes asking for tens of thousands of pounds. This was especially problematic for smaller employers.

3.3 What factors shape whether participants settle at post-tribunal claim conciliation?

Factors that shaped whether claimants and employers settled at the post-tribunal claim conciliation stage included the conciliation experience, and whether this brought parties closer together. This interacted with the length of time it took to get to a full tribunal hearing, personal and circumstantial factors, and whether new information was identified that encouraged one, or both, parties to settle before the hearing.

Summary of the factors shaping decisions to settle at post tribunal claim conciliation.

Personal and circumstantial factors:

- Level of stress, impact on mental health

- Being able to afford the costs of tribunal

Timing issues:

- Length of time it took to get to full hearing

Factors related to conciliation:

- What type of conciliation contact parties experienced and whether they went through judicial mediation

- New information that led to compromise and settlement

3.3.1.What were participants' experiences of conciliation in employment tribunal applications?

There was a great deal of variation in what claimants and employers described as having happened at the post tribunal claim conciliation stage, and so experiences of conciliation varied at this point. In addition, some participants participated in judicial mediation as a step prior to a full tribunal hearing that, in some cases, had supported them to come to a settlement.

No or limited contact from Acas. Some claimants said they could not recall any contact or involvement with Acas at this stage. Here, it should be borne in mind that for Acas conciliation to happen, both parties must first agree to participate. Where they did recall Acas contact, some claimants said it was limited to discussion about processes or timings of the next steps towards tribunal. Participants also said that contact was limited to a few emails or phone calls.

Some claimants and employers were disappointed that the parties were not brought together, either again or for the first time, to try to resolve the issues at this point. There was a strong sense that claimants were unclear about what Acas's role was at this stage:

"I think maybe someone called me to say, 'Okay, you're going through conciliation. I'm the person overseeing it'. But I don't actually know what they did..." (Claimant 7, public sector, over 250 staff).

Acas relaying information to reach and write COT3 agreements. Those who did recall more contact described Acas's role as principally to 'relay information' between parties, and to write up COT3 agreements where they decided to settle. While some claimants and respondents welcomed the fact that they did not have to deal with the other party directly – thereby reducing the level of anger, hostility, or rashness in communications – others said Acas simply conveyed that the other party had refused to conciliate or move position. This served to reinforce feelings among these claimants that Acas was not adding value to the communications and added to feelings of frustration.

One of the most prominent frustrations expressed about contact with Acas at post-claim conciliation stage, was that it did not help the customer gain more clarity about the strength of their case based on good practice or points of law. Participants felt that there was too much emphasis on 'process' and 'timings', and not enough on their substantive case. In some instances, this made claimants feel pressured to settle a dispute when they felt unclear on whether they were more likely win or lose:

"I wanted to know what my position was … I wanted to know legally had I done everything right and was I legally being discriminated against... That's why I turned to Acas for information on that" (Claimant 7, public sector, over 250 staff).

"Acas should be able to give advice to claimants in regard to the potential success of their claim" (Employer 12, private sector, 10 to 49 staff).

While some claimants and employers realised that Acas is not supposed to give advice on the strength of a case, they nonetheless wanted direction to information that would allow them to judge this for themselves. It was when participants felt that they had not received this signposting that they were most critical of Acas and their conciliators. For some, this made contact with Acas conciliators feel more frustrating than helpful.

However, it was also true that when conciliators were perceived as giving advice, this could also lead to negative reactions (for example, a claimant who felt they had been incorrectly advised to drop a race discrimination element from their claim; an employer who said the advice given to them made them think the conciliator was siding with the claimant).

Nevertheless, claimants and some employers said that better signposting to information that would help them assess the strength of their claim, and whether it made sense to go to tribunal or settle, would have been helpful. Chapter 4 discusses the types of information customers wanted.

Employers were more likely to be positive about Acas's role and tended to have a better understanding of the limitations on the advice conciliators could offer. They were particularly positive where they thought that their conciliator had helped bring both parties together, thereby promoting better understanding of each other’s position. Where this led to a settlement, they also said that Acas had been helpful in pulling together the details of the ensuing COT3 agreement.

Judicial mediation. A sub-group of the study sample told us they had been through judicial mediation. Judicial mediation is provided by HM Courts and Tribunals Service and is not an Acas service. It involves bringing the parties together for a private preliminary hearing before a trained Employment Judge. Judicial mediation is suggested by the Judge in cases where the issues in dispute are deemed suitable and there is potential for settlement, and often where there is an on-going working relationship to preserve.

Judicial mediation was described in different ways by participants, but usually involved a Judge or Judicial Officer. There was no direct involvement by Acas in judicial mediation, although Acas were usually described as having been involved in writing up COT3 agreements where this process led to settlement.

While some claimants described finding judicial mediation formal, scary, or intimidating, others found it helpful in deciding whether to settle or to proceed to a full hearing. Among these participants were claimants and employers who said that the nature of judicial mediation had encouraged them to look more closely at the strength of their case, and to see where they might be prepared to compromise (for example, an employer agreed to make a payment to a claimant provided he dropped the idea that he should be reinstated in his job). In particular, they said that they liked 'getting around the table' which had the advantage of getting the issues resolved more quickly. For some, there was a benefit in the formality of having a Judge present; this made them decide they did not want to go to full hearing. For instance, one employer said the claimant contacted them shortly after judicial mediation to make what they considered to be a more acceptable offer to compromise.

3.3.2.What factors shape decisions to settle at conciliation in employment tribunal cases?

Decisions to settle were grouped around three sets of factors:

- length of time the employment tribunal process took

- personal and circumstantial issues

- new information that led to compromise

These are discussed in turn.

Length of time the tribunal process took. The amount of time it took to get to a full hearing could push participants to settle sooner. Employers sometimes just wanted the case 'resolved'. Claimants talked about the length of time the case was 'hanging over them'.

Sometimes the length of time it took for cases to reach tribunal also meant that circumstances changed, and claimants decided to reach a settlement on that basis. For instance, one claimant who had felt discriminated against during a recruitment process, said they decided to settle with a payment when they realised the job that they wanted was no longer available. In another case, a claimant settled their claim when a new manager took over who struck a more conciliatory tone in negotiations.

Personal and circumstantial issues. These issues fell into 2 broad areas:

- stress and poor mental health

- costs (financial, reputational or both)

The amount of time, effort and stress involved in preparing a case for tribunal, and its impact on people’s mental health, was one of the most prominent reasons discussed for deciding to settle a dispute. For some claimants, the fact that they experienced depression or anxiety in the first place made them fear breaking down or having a panic attack at the hearing. Other claimants emphasised that it was the continuation of the dispute itself which made them so unwell, and that therefore made them decide to settle.

Claimants also felt that it was unfair that they were required to prepare for a tribunal at a time when they were mentally so unwell, with problems of anxiety, depression, difficulties concentrating, and sometimes suicidal thoughts. For example, one claimant said:

"I was exhausted with the process. It was really upsetting and stressful… I just wanted it to be over" (Claimant 7, public sector, over 250 staff).

While it tended to be claimants that raised these issues, employers and human resources participants also wanted to avoid the stress of a full hearing, especially when they had been to tribunal before.

Another prominent factor influencing decisions to settle at this stage for both parties was costs. This included both court costs if a party lost the case, and the potential size of an award if the employer lost. It also included broader costs in terms of reputational damage to the organisation , or the costs to the claimant of seeking employment in future if they had no job reference. Because the research focussed on unrepresented parties only, the costs of professional representation were not discussed as a relevant factor.

New information leading to compromise. Here participants talked about new information becoming available that had not been ready at the time of early conciliation or prior to the deadline to submit the tribunal claim form. In some cases, this new information arose through judicial mediation because a Judge advised on the likelihood a claim would succeed. In other cases, it came to light because of preparations for hearings. In both instances this tended to clarify the strength of a claim and the likelihood of having a claim upheld if it went to full hearing. It was here that participants thought conciliation could have a greater role in highlighting new information that could help facilitate earlier compromise or settlement.

An example of the type of new information that arose at this stage was where an occupational health assessment was conducted after the tribunal claim form was submitted. The assessment said that the claimant was not capable of returning to their job due to their disability and could not be re-deployed elsewhere in the organisation. The claimant therefore decided to settle for a compensation payment to leave the employer.

"In some cases [HR] will say, 'Right, yes, there's been mistakes made here, let's close this down'" (Employer 5, public sector, over 250 staff).

Significantly, the time pressures, stress, likely costs, and perceived strengths of claims, could also combine to make parties accept a partial resolution or compromise. An example was a claimant whose dispute involved discrimination based on both their dyslexia and their stated need as a wheelchair user to work in the office when they chose to due to procedures needed for fire evacuation. Eventually, after several months, their employer made reasonable adjustments for their dyslexia and they ultimately decided it was too much stress to follow-up the other part of the claim that related to their mobility impairment.

For employers and claimants, partial resolution or compromise involved moving closer to an agreed acceptable level of payment to the claimant, sometimes with the claimant accepting that they could not return to their job due to capability, unprofessional behaviour, or breach of contract.

For those who did not settle or did not engage in post-claim conciliation, the reasons reflected those discussed in section 3.2.2. These included:

- Having no case to answer, or 'doing nothing wrong' – as noted above, some employers believed that they had not discriminated against a claimant, either substantively or in their management of the case.

- Justice, fairness or 'righting a wrong' – the fact that some employers appeared not to want to engage with claimants at all, made some claimants feel that real changes in working practices for disabled employees would only come about through them going to a full tribunal hearing.

- In other cases, the desire to go to tribunal came from claimants' desire to 'clear their name', especially where future references or reputation were involved.

- Level of payments – the level of payment offered or requested was a key reason why the other party would not conciliate. For instance, one claimant said they were basically offered the pay that they were still owed to leave their job, which they felt did not recognise the discrimination they had experienced.

By comparison employers were less likely to engage with conciliation in tribunal claims where they thought the level of compensation being sought was totally inappropriate. One employer said that the claimant was seeking £30,000 from their small company. Their decision to go to a full hearing was because they said the requested amount would bankrupt their organisation.

3.4 What are the parties' experiences of tribunal hearings for disability discrimination claims?

Both claimants and employers found the experience of full hearings difficult, although it was described in starker terms by claimants. It should be noted here that all the interviewees in this study represented themselves at tribunal, which is relevant in explaining their strength of feeling.

Experiences of employment tribunal hearings. Claimants invariably described their experiences of going to full hearing as 'nerve wracking', 'horrific', or 'soul destroying', sometimes because claimants already experienced anxiety, panic attacks, depression, or physical illness. One participant described the experience as stressful, but 'exhilarating' because they felt they had learnt so much about their disability and the law. However, a recurring theme for claimants was that going to full hearing was an extremely 'painful' experience, especially where claimants were from smaller organisations previously had close working relationships with colleagues giving evidence against them.

Employers said they also found the experience of full hearings 'difficult' and 'stressful', but this was not to the same extent of the pain expressed by claimants.

Experiences of self-representation. The 'painful' experience of tribunal hearings for claimants was also exacerbated by the fact that they had all represented themselves in court. Reasons for self-representation were to do with legal costs that they could not afford or the fact that they were not trade union members, or else had not found their union to be helpful. Consequently, they often sought advice and support online or from family and friends who had legal expertise (see chapter 2, section 2.2.1).

At the tribunal hearing, claimants said they felt 'alone', 'inexperienced' and 'out of their depth'. As one claimant put it, their employer 'ran rings' around them.

By comparison, employers said they represented themselves with recourse to their organisation's own experienced HR professionals, internal legal departments, or by employing legal consultants who advised on the case. While some smaller employers who represented themselves said they had not been sure what to expect, they had nevertheless felt relatively confident in their position. This therefore indicates an imbalance in legal support for employers and claimants.

3.5 How satisfied are claimants with the outcome of their claim and what shapes satisfaction?

There were no claimants in the sample who had fully won their case. Among those included were claimants who won elements of their claim and received a smaller settlement than they wanted. Others completely lost their case. Even those who were most determined to go to full hearing, sometimes said that in retrospect it would probably have been better to settle earlier due to the impact on their health. This was because the effect on their health was disproportionate to the sense of justice or righting a wrong that they hoped for. Whether claimants partly won or lost their claim, they described feeling 'deflated' or 'disappointed'.

Those who found the judgement hard to accept said the experience was very detrimental to their on-going mental health. This group described tribunal judges as 'biased' or 'ignorant', often in very angry terms.

Employers in the sample tended to be far happier with the tribunal outcome, although some still expressed frustration where they lost in full or a part of a claim. Those who were most satisfied with the case outcome said they felt 'vindicated' that they had followed correct policies and procedures, and sometimes the disability element of the claim, which they felt was spurious, was thrown out. An example was a school that had dismissed a member of teaching staff over what they saw as an issue of incompetence. They felt the claimant only mentioned mental health issues when an internal disciplinary found against them, and the case went to appeal. Employers also said they found the employment tribunal panels 'reasonable' in their judgements.

4. How can Acas's handling of disability discrimination cases be best developed?

This chapter explores participants' views on how Acas could provide further guidance on the handling of disability discrimination in the workplace and develop its conciliation offer. It describes what customers wanted from conciliation, and their suggestions for improvements. It also discusses what advice and information Acas and other organisations could provide to help prevent disability discrimination occurring, or else to resolve claims earlier, with less cost and stress to both parties.

4.1 How can conciliation in disability discrimination cases be improved?

4.1.1. Parties' views on conciliation services

Larger employers, who had legal representatives or consultants or dedicated human resources staff, were most positive about the conciliation service, saying it was 'excellent' and 'invaluable', and describing conciliators they had worked with as 'knowledgeable'. Other employers and some claimants felt their Acas conciliator had done the best they could in difficult circumstances given the perceived intransigence of the other party. Claimants were more positive about it where they felt it had enabled them to get more information from their employer, helped understand the other party's position and had formalised the process of communication.

By comparison, another group of customers were highly critical of conciliation, both at the initial early conciliation and subsequent post-claim stage. This group consisted of both claimants and smaller employers who felt the service had not helped in any way. Underlying this perspective was their belief that:

- the purpose of conciliation was unclear

- there was too much emphasis on process and timings of tribunal stages, rather than the substance of the claim and actual 'conciliation'

- that the service did not offer enough advice or signposting (for example, on what constitutes disability discrimination, the nature of reasonable adjustments, and the likely strength of a claim)

Some claimants said they had found contact with Acas conciliators to be frustrating, an experience they described as being more a 'hindrance than a help'.

4.1.2. Suggested improvements to conciliation services

Suggested improvements to conciliation services advanced by interviewees focused on 3 issues:

Improving awareness of the conciliation offer, including communicating it and adapting it to the needs of disabled people. As outlined in section 3.2.1, some users (claimants and employers) did not fully understand what 'conciliation' meant or fully understand the service being offered. This meant some did not take part in early conciliation, or fully engage at this or the later stage.

There was some evidence that this resulted from Acas not communicating with claimants in ways suited to their disability (especially for people with dyslexia who preferred spoken communication, and others who were neurodivergent who liked written communications). They emphasised the need for communication in different formats and understanding that disabled people may have different communications needs:

"So, understanding that and not treating everybody the same is knowledge that I felt that was missing" (Claimant 12, third sector, over 250 staff).

Disabled claimants also emphasised that their disability or health condition made them more vulnerable relative to other types of claims (for example, alleged discrimination relating to a mental health issue compared to non-payment of wages). As one participant explained, they felt that people submitting disability discrimination claims needed to be taken care of more than most:

"When anybody rings Acas with a disability discrimination case (...) they really need to be looked after and given all the help and all the support that can possibly be given" (Claimant 14, public sector, over 250 staff).

Making conciliation more proactive. At both early and later stages of conciliation, employers and claimants wanted conciliators to be more proactive in persuading both parties of the benefits of taking part in conciliation. Employers said conciliators could take a greater role in repairing broken working relationships, bringing parties closer to understanding each other's positions, and exploring areas of compromise or reasonable compensation (for example, highlighting occupational health assessments, reference to case law). Claimants and employers said conciliation needed to be more than just 'relaying messages'. In describing what they would like from the service, both employers and claimants described wanting more of a mediation-type service.