Disclaimer

This is an independent, evidence-based research paper produced by Richard Saundry (University of Sheffield), Virginia Fisher (University of West England) and Sue Kinsey (University of Plymouth).

The views in this research paper are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the authors alone.

For any further information on this study, or other aspects of the Acas research programme, email research@acas.org.uk.

Executive summary

Over the past decade, Acas has developed a comprehensive programme of research into the management of workplace conflict. This work has identified the emergence of a ‘resolution gap’ as informal processes of resolution have been eroded. Moreover, it has suggested that changes in the nature of the HR function may have been a contributory factor. However, to date, there has been no specific research that primarily focuses on this important issue.

This research considers academic and practitioner literature on the evolving nature of the human resource (HR) function and its implications for workplace conflict. It draws on 31 in-depth semistructured interviews with HR practitioners, to assist in the understanding of how different models of HR management (HRM) relate to the way in which conflict is managed and to assess the place of employment relations within current HR practice.

The evolution of the HR function

Our findings paint a relatively clear picture of how HR structures evolve as organisations develop and grow. This begins with generalist approaches to HRM in smaller organisations which locate the management of conflict as a core HR activity. Even among HR practitioners in these settings there is a clear ambition to be more ‘strategic’. This is inextricably linked to the devolution of people management responsibilities to line managers.

In the HR functions of most large organisations there is a clear separation between specialist services, operational HR advisers and ‘strategic’ HR business partners. The location of employment relations advice varies: in multi-site organisations it tends to be remote and centralised while elsewhere, it is largely the responsibility of HR advisers.

The nature of HR work

While generalist HR practitioners in smaller organisations tended to play down their work as ‘day-to-day’, some operated at a strategic level across the full range of HR activity, working in close partnership with senior operational managers, providing advice over resourcing and relations issues.

In larger organisations HR business partners were directly linked to, and in some cases embedded within, an area of the organisation. Moreover, they claimed that their focus was ‘strategic’ rather than ‘operational’ – working with senior leaders around planning, resource and talent management. In terms of Dave Ulrich’s fourfold typology, there was little sign that most HR business partners saw themselves as ‘administrative experts’ or ‘employee champions’.

Conflict management was a consequence, but not part of, strategic considerations. It was therefore secondary to the overarching role of the business partner. Work related to employment relations and the handling of conflict was seen as operational, ‘day to day’ and transactional. This view of employment relations as adding less value was reflected in the status and influence of employment relations advisers.

Our research found this stereotype is too simplistic. In addition to basic administrative elements such as arrangements for investigations and hearings, note taking and compliance checking, employment relations specialists provide guidance over issues with complex legal implications, were vital in building managerial competence and played a mediating role between employees, managers and trade unions.

Practitioner perspectives

Expertise in conflict management and employment relations was not seen as a path to career success for most HR practitioners. Instead progression was associated with leaving such work behind. In short employment relations has become counter aspirational. This raises the possibility that the marginalisation of employment relations could lead to a shrinking body of skills and expertise.

For many respondents, consistency was a vital element in ensuring fairness and therefore organisational justice. Moreover, this was seen as a fundamental part of the role and identity of HR practitioners. In this way it could be argued that HR had an opportunity to go beyond being the keeper of procedures and instead be relied upon as ‘advocates’ for doing things in a fair and proportionate way.

Implications for conflict management

There was general support for the idea that high trust relationships between key stakeholders underpinned effective conflict resolution. However, the marginalisation of employment relations was reflected in more centralised and remote systems of advice and guidance. Respondents felt that this resulted in more compliance focussed advice and encouraged cultures of avoidance among line managers.

The separation between HR business partners and practitioners specialising in employment relations made early resolution of conflict less likely. Conflict management was a second order activity whereby HR business partners would ‘commission’ employment relations advice if conflict occurred. Therefore, responses to conflict were inevitably reactive, late and focused on the management of risk.

The success of HR business partner models ultimately depends on managers having the confidence, capability and the time to manage people and resolve conflict. This research lent further weight to previous studies that have identified the lack of confidence of line managers in handling conflict and the priority given to production imperatives over people-related issues. Managers were prone to either avoid difficult issues or fall back on process. This meant that often HR was forced to adopt more reactive positions to conflict.

This lack of confidence and capability meant that many HR practitioners were not able to ‘let go’. In most organisations, there was evidence of informal processes being formalised and the widespread use of management tools – such as checklists, flowcharts, and templates. While most HR practitioners rejected their role in ‘handholding’, this has been replaced by longer ‘reins’.

A number of respondents also argued that real devolution was unrealistic given the expectations and pressures placed on some line managers. There was a view from some respondents that, while upskilling and empowering line managers was important, HR should maintain an active role in managing employment relations issues.

A new vision for employment relations within the HR function

The current debate over good work offers the potential to reassert the significance of employment relations and in foregrounding fairness at work taps in to a fundamental motivation for many practitioners. Fairness needs to be a core consideration of HR practitioners working at the highest level. This, in turn, requires a return to more ‘generalist’ approaches to HR and business partnering challenging the false dichotomy between what is considered either ‘strategic’ or ‘operational’.

HR practitioners at all levels need to see building the competence of line and operational managers as a principal goal. Fairness underpins trust which is an essential pillar of productive workplaces. This makes complex demands on managers that go beyond procedural adherence. Instead managers need to develop the skills to build positive relationships with staff and resolve difficult issues when they arise.

Proximity between HR and the line is vital. High trust relationships provide a foundation for more informal and nuanced solutions to workplace problems. Our research has also shown that the coaching role of HR practitioners is essential in building the confidence of line managers to address the difficult issues that they will inevitably face.

1. Introduction

According to the 2011 Workplace Employment Relations Survey, more human resource (HR) practitioners spend time dealing with discipline and grievance than any other issue including recruitment and learning and development (Van Wanrooy and others, 2013).

Therefore the management of workplace conflict remains a core element of human resource practice. However, there is arguably a tension between this reality and the ambition of the HR profession to adopt a more strategic role. This ambition is reflected in the widespread adoption of business partner models of human resource management (HRM). Although this has been operationalised in various ways, an essential component is the separation between what are perceived as strategic and transactional activities.

Acas research has emphasised the key role played by HR practitioners in the management of conflict. In particular, it suggests that where they are able to develop high levels of trust with line managers and employee representatives, informal and creative solutions to workplace problems are more likely (Jones and Saundry, 2012; Saundry and Wibberley, 2014).

However, the most recent study in this area (Saundry and others, 2016) found tentative evidence of a number of barriers to HR practitioners contributing to effective conflict resolution in this way.

Barriers were:

- in some organisations, employment relations advice has become remote from the workplace, with fewer onsite HR practitioners

- in-house HR practitioners increasingly find themselves at odds with external providers of HR advice

- employment relations in general, and conflict management in particular, is seldom seen as a strategic priority

It went on to argue that these factors could encourage an emphasis on procedural and legal compliance as opposed to a focus on the promotion of positive relationships inside the workplace.

This report draws on data from 31 in-depth interviews with HR practitioners to explore their attitudes to workplace conflict, the role they play in handling difficult employment relations issues and how different HR structures influence organisational approaches to conflict management. More specifically, the report:

- examines the evolution of HR organisation and structure and the role of HR business partners

- assesses the status of employment relations and conflict management within different HR structures

- explores the extent of devolution of responsibility for conflict management to line and operational management

- examines the implications of the development of the HR function for employment relations and the effective management of conflict

- explores the potential for creating a renewed role for employment relations within the HR profession

2. Background and context

2.1 The development of the HR function

In much of the academic and practitioner literature relating to people management, HR functions in 21st-century organisations are represented as having evolved through a series of relatively discrete incarnations, each with a particular orientation, each offering an improvement on previous practice in the management of employees.

According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), the professional body for HR and people development in the UK, the development of the function has its origins in the emergence of a welfare remit in the early 20th century, primarily focused on social and occupational health issues and with working conditions in factory environments.

A concern for formalising record keeping and more hands-on management of the workforce then gave rise to the Institute of Labour Management, ‘to assist in the management of recruitment, discipline, dismissal and industrial relations at plant level amongst unionised male workers’ (CIPD, 2017).

The middle of the 20th century heralded the arrival of personnel management which was chiefly concerned with obtaining, organising and motivating the required human resources (Armstrong, 1977) and with the maintenance of good industrial relations.

Each of these ‘incarnations’ suggests a relatively operational and ‘hands-on’ orientation for the function, embedded in people management practice and with a central role for the management of workplace conflict. However, the advent of human resource management (HRM) signalled a unitarist orientation for the function. This was accompanied by, and arguably linked to, the decline in collective regulation of labour in the UK and created a dominant ‘new orthodoxy’ for people management focussed on business performance and strategy (Guest, 1991).

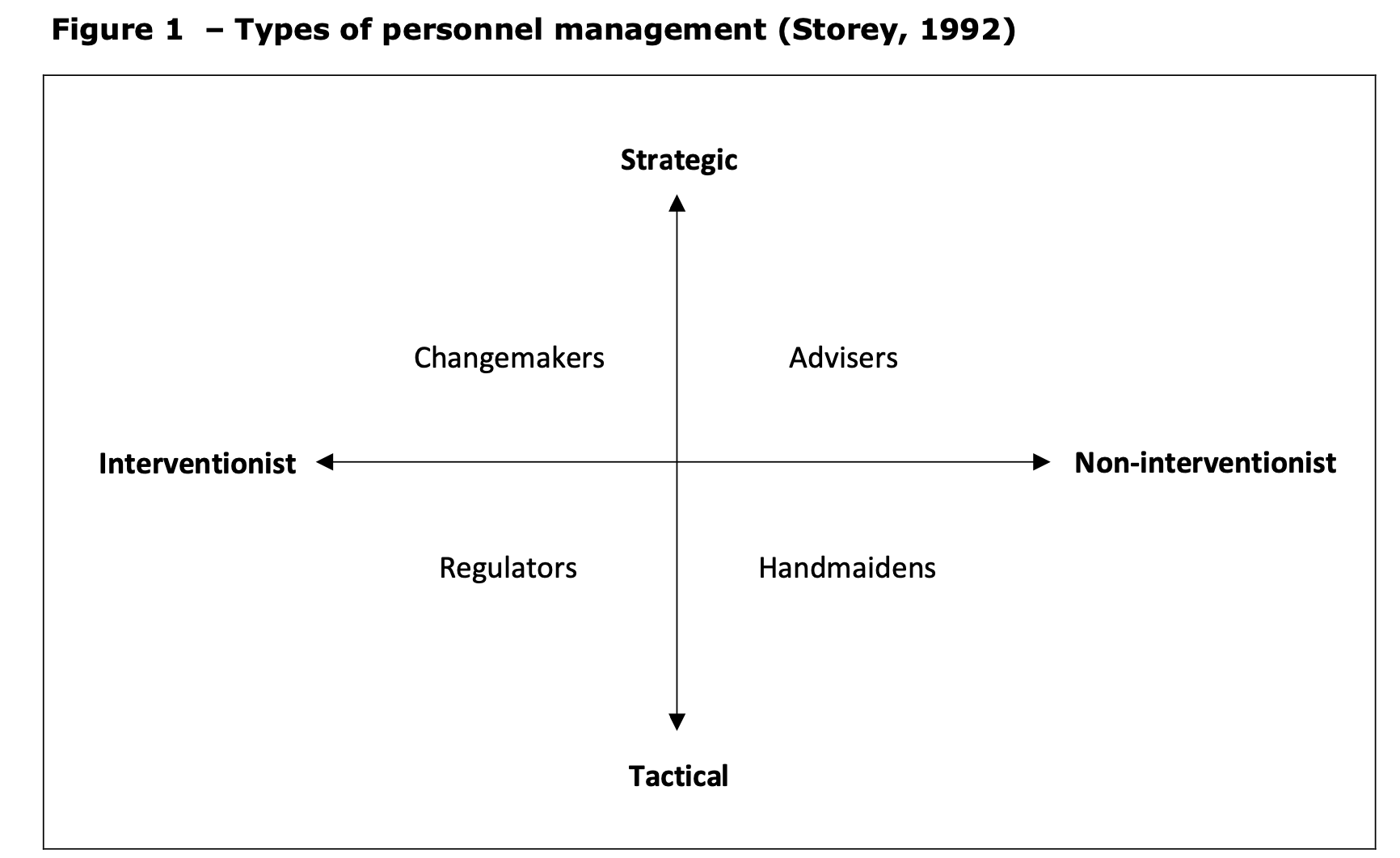

In the late 1980s, John Storey began to chart the transformation of the management of human resources through detailed empirical research (Storey, 1992). He identified 4 main types of ‘personnel specialists’ distinguished by the strategic nature of the role and the extent of their intervention in the management of people.

In simple terms, traditional personnel management centred on an interventionist, regulatory role and revolved extensively around the management of workplace conflict. For Storey, ‘regulators’ were “managers of discontent, seeking order through temporary, tactical truces with organized labour” (Storey, 1992). A key aspect of this role was the development, application and enforcement of rules ranging from policy and procedure to collective agreements.

However, Storey was beginning to see changes in the personnel function in response to the growing influence of HRM. Perhaps foremost of these was the devolution of responsibility for employment relations to line managers, hastened by moves in large organisations to decentralise accounting and bargaining arrangements.

In this context, Storey noted a typical shift in the role of personnel from an “up-front contracts manager to whom line managers were expected to defer on labour-relations matters… to a state of affairs whereby personnel stepped back and adopted a customer-led approach”.

In some cases, the personnel manager acted as what Storey termed a ‘handmaiden’, reacting to the demands of managers and working under an implicit contract of service. This noninterventionist role could become more strategic as personnel managers acted as expert ‘advisers’ and internal consultants.

However, some personnel managers were going further in their strategic ambitions, “seeking to put relations with employees on a new footing”, one aligned with needs and focussing on employee engagement as opposed to labour regulation.

These ‘changemakers’ were not only the closest fit with HRM principles but also represented a shift away from labour regulation and conflict management. As Storey argues they were the ‘antithesis’ of “bargaining, ad-hocery and humble advice”.

Furthermore their focus was on 'resourcing, planning, appraising, rewarding and developing'. Although this typology inevitably underplayed the complexity and overlapping nature of personnel or HR roles (Caldwell, 2003), it reflected a very significant shift in the orientation of the developing HR profession away from proceduralism and pluralism, and the birth of the idea of HR as ‘business partner’.

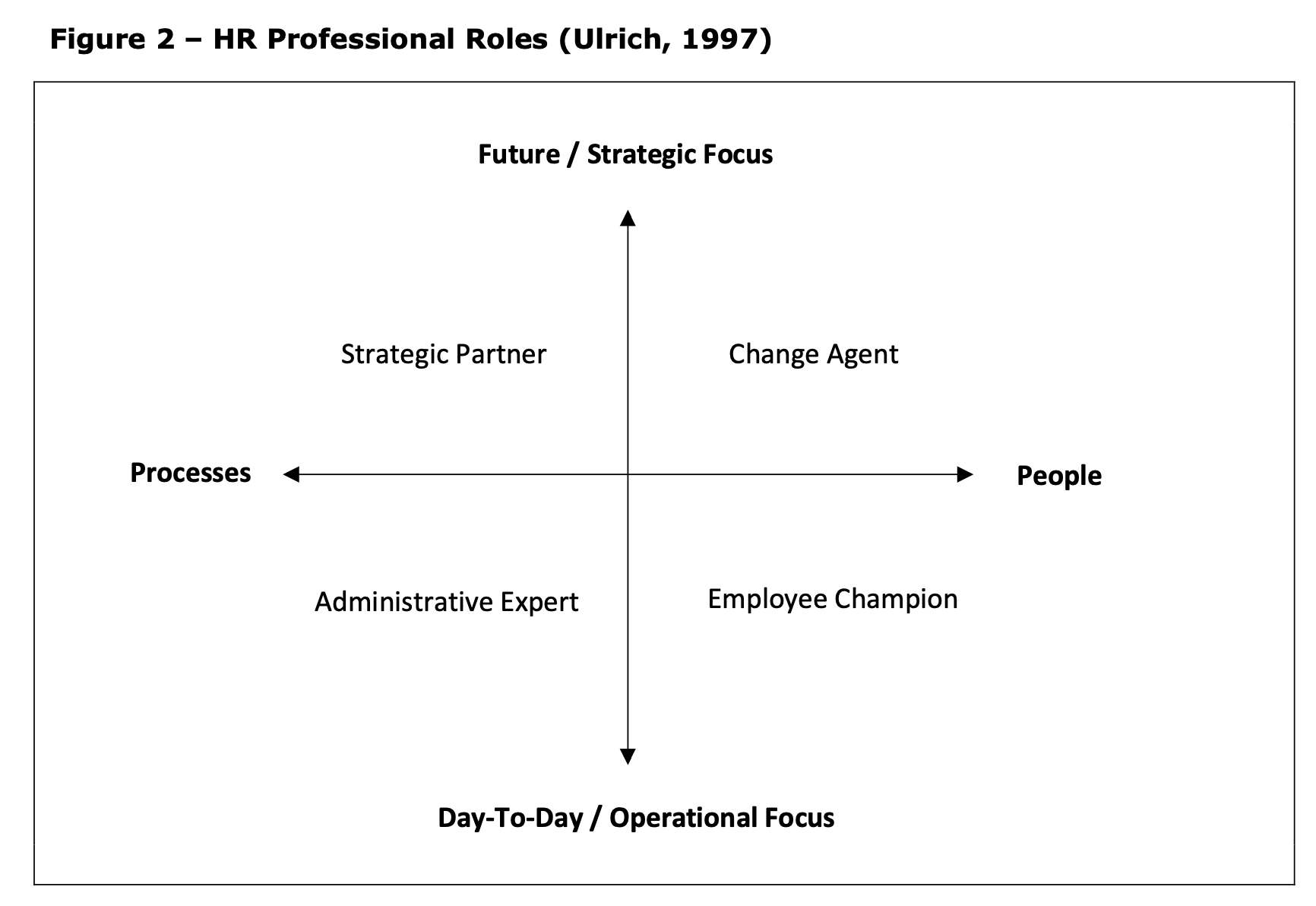

Despite closer alignment with business objectives, there was evidence of a progressive decline in the representation of senior HR professionals on the boards of UK companies (Cranet, 2006; Kersley and others, 2006; Caldwell, 2011). It might be argued that the erosion of collective regulation left personnel and HR searching for a new role and renewed legitimacy. Into this gap Ulrich’s prescriptive framework of HR roles aimed to provide a ‘mandate’ for HR professionals focussed on organisational excellence and competitive advantage (Ulrich, 1998).

He set out 4 ways in which HR professionals could help to achieve this (see figure 2).

Firstly, at an operational or day-to-day level, HR professionals should be administrative experts. However, in contrast with Storey’s ‘regulators’, their main concern should be the efficiency of processes, not acting as custodians of procedure.

Second, Ulrich argued that HR should act as employee champions tasked with maximising employee engagement but also being ‘an advocate for employees’ representing them and being their ‘voice in management discussions’.

Third, in terms of their strategic role, like Storey, Ulrich emphasised the importance of HR professionals acting as agents of change.

Fourth, and perhaps most importantly, he argued that they should become partners in strategy execution.

Importantly for this report, Ulrich suggested that strategic business partners should be concerned with defining a developing organisational architecture including culture, competence, reward, capacity to change and leadership.

Ulrich’s mandate for the HR profession also involved jettisoning what are perceived to be transactional activities, which can instead be outsourced, automated or standardised (Ulrich and Beatty, 2001; Ulrich and Brockbank 2005a; Ulrich and Brockbank 2005b).

While there is no explicit mention of conflict management, activities classed as ‘administrative’ include policy setting, union negotiation, and the negotiation and management of terms and conditions. This has been translated into what has become known as the ‘3-legged stool’ model, consisting of: HR business partners working closely with managers in developing and executing strategy, often embedded in business units; centres of expertise with specialist HR knowledge in specific areas; and shared services which provide more routine transactional services.

There is little doubt that the idea of the strategic business partner has become central to the contemporary identity of HR professionals (Wright, 2008; Pritchard, 2010; Keegan and Francis, 2010). Importantly, some authors have suggested that this has been at the expense of the employee champion or advocate and change agent roles also advocated by Ulrich (Hope-Hailey and others, 2005; Francis and Keegan, 2006; Harris, 2007).

Although, it could be argued that this is based on an oversimplification of Ulrich’s proposition (Reilly and others, 2007) it nonetheless represents a realignment from the more traditional role played by HR professionals in balancing the employment relationship towards one predominantly focused on business performance (Francis and Keegan, 2006).

This appeals to HR professionals on 2 levels: first it offers a degree of parity and integration with managers. The idea of partnership suggests that HR are working with, rather than simply providing a service to, managers. Second a strategic identity that ties people management to business imperatives arguably gives HR greater potential legitimacy (Caldwell, 2001; Brown, 2004; Kulik and Perry, 2008).

Whether the prominence of the ‘Ulrich model’ in debate and discourse is reflected ‘on the ground’ is unclear. In fact there is limited evidence of HR functions embracing entirely strategic roles and abandoning previous ‘traditional’ HR activities. Roche and Teague (2012), for example, conclude that in times of recession, where organisational survival and business viability are the primary concern, a strategic role for the HR function may involve engaging in hands-on employee relations roles and activities, including the design and implementation of pay and headcount management policies, restructuring, and even union negotiation.

Thus, whatever HR’s aspirations may be, their role is likely to be shaped by local, contextual factors and demands (Roche and Teague, 2012; McCracken and others 2017; Wylie and others, 2014). This suggests that HR practitioners are capable of juggling multiple, complex, hybrid roles and of adapting readily to new circumstances and demands. HR practitioners are engaging in daily negotiations about what their priorities should be and how they should engage with the business and line management, rather than cleaving to an overarching set of prescriptions about their role (Pritchard 2010; Pritchard and Symon, 2011).

2.2 Devolution and the management of conflict

The ability of HR practitioners to focus on what are perceived as strategic issues inevitably depends on the ability to devolve operational aspects of people management to line managers (Kulik and Perry, 2008; McCracken and others, 2017).

However, there is evidence to suggest they are still undertaking many of the roles and activities associated with more traditional and interventionist models of personnel management (Truss and others, 2002; Truss, 2003; Teo and Crawford, 2005).

For example, handling disciplinary cases and employee grievances remains a core activity for many HR practitioners. According to the Workplace Employment Relations Survey 2011, 92% of workplace HR managers spent time dealing with these issues (Van Wanrooy and others, 2013).

Furthermore, their place as procedural specialists and legal experts has, if anything, been accentuated due to increased concerns over litigation and juridification of employment relations (Heery, 2010).

One explanation for this, according to research evidence, is that HR practitioners have a fairly negative view of the abilities of line managers to handle and resolve conflict. In 2007, a CIPD survey of its members found that around two-thirds felt that line managers were either average or poor at resolving disputes informally (CIPD, 2007:12).

More recently, a survey conducted by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) of HR practitioners found that 83% of respondents claimed that ‘senior leaders’ were ‘very’ or ‘somewhat effective’ in demonstrating technical skills, this fell to 50% in respect of ‘managing difficult conversations’ and only 38% in respect of ‘conflict management’ – the lowest score of 15 competencies that the survey covered (CIPD, 2016).

This is particularly problematic when the contemporary emphasis on more robust approaches to the management of absence and performance (Hales, 2005; 2006/7; Dunn and Wilkinson, 2002; Newsome and others, 2013) making it more likely that managers will be faced with having ‘difficult conversations’, and finding themselves in conflict, with their subordinates.

It might be suggested that this forms the basis for a somewhat antagonistic relationship between HR practitioners and operational managers. HR’s goal of compliance and pursuit of consistency comes into conflict with the desire of line managers for flexibility and informality, and also an aversion to the time and bureaucracy associated with process and procedure (Jones and Saundry, 2012).

That said, Cunningham and Hyman (1999) found that line managers welcome HR advice and guidance while other studies have suggested that managers welcome the ‘cover’ and certainty provided by procedure (Cooke, 2006; Cole, 2008).

It should also not be assumed that HR practitioners themselves have both the knowledge and confidence to manage conflict effectively. The range of skills and expertise needed to manage conflict should not be underestimated (Renwick and Gennard, 2001). It is perhaps not surprising therefore that the CIPD (2015:3) have argued that ‘many HR managers lack confidence in developing informal approaches to managing conflict and continue to be nervous about departing from grievance procedures’ (2015:3).

The consequence of these tensions is arguably that a relationship of dependency has developed between HR practitioners and line managers which contradicts the rhetoric of devolution. In the absence of adequate training, this is unlikely to be simply broken by the ‘withdrawal’ represented by attempts to move to a more strategic, business partner approach. Instead, it could be argued that rather than making managers more self-reliant, the increased distance between HR practitioners and line managers threatens to further embed risk averse approaches to the management of workplace conflict (Saundry and Jones, 2016; Whittaker and Marchington, 2003; Keegan and others, 2011).

3. Research design

The research has 2 main parts. The first comprised of in-depth semistructured interviews with HR practitioners. The sample was designed to reflect a range of organisational contexts but also different HR roles and levels of seniority.

A description of the sample is provided in Table 1.

| Number | Sector | Organisation size | HR structure or operating model* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Tourism and Hospitality |

150 to 250 |

Traditional Personnel |

| 2 |

Private services |

150 to 250 |

Traditional Personnel |

| 3 |

Private services |

Over 1,000 |

Hybrid HR – moving to Remote HR |

| 4 | Private services | Over 1,000 |

Classic HR |

| 5 |

Public sector |

Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 6 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 7 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 8 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 9 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 10 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 11 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 12 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 13 | Private services | 100 to 150 | Traditional Personnel |

| 14 | Retail | Over 1,000 | Remote HR |

| 15 | Private services | 100 to 150 | Traditional Personnel |

| 16 | Tourism & hospitality | 500 to 1000 | Traditional Personnel |

| 17 | Manufacturing | Over 1,000 |

Hybrid HR – moving to remote HR |

| 18 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 19 | Public sector | Over 1,000 |

Generalist Progressive |

| 20 | Not for profit | 250 to 500 |

Generalist Progressive |

| 21 | Private sector | 250 to 500 | Generalist Progressive |

| 22 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 23 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 24 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 25 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 26 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 27 | Public sector | Over 1,000 |

Traditional Personnel |

| 28 | Retail | Over 1,000 |

Hybrid HR – moving to Remote HR |

| 29 | Manufacturing | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 30 | Manufacturing | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

| 31 | Public sector | Over 1,000 | Classic HR |

* For descriptions of structure/operating model see Figure 3

In some organisations further interviews were undertaken with a wider range of HR practitioners and where possible line managers to provide a more detailed analysis of particular ‘case-study’ contexts. Furthermore, in one organisation, one of the researchers attended a line manager ‘conflict management’ training day. In broad terms these organisations were selected based on potential access but also to represent the range of different HR structures.

Thirty-one interviews were conducted, which provided around 35 hours of data. The majority of these were carried out face to face and 5 by telephone. A generic topic guide and semi-structured approach was used focusing on building a detailed picture of the attitudes and experiences of respondents. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Anonymised transcripts were then sent to respondents for their approval.

In the second part of the research, a draft coding schema was created by the 3 researchers based on their initial perceptions of the interviews, with key themes identified.

This was then used to analyse the data with new categories introduced, with a range of sub themes identified, examined and refined.

The study explores theories on the structures and changing nature of HR, considering impacts on conflict handling at work using data from the qualitative research.

4. Findings

4.1 The evolution of the HR function

The interviews revealed a number of different models of HR management. These are set out in Figure 3. While these categorisations inevitably mask a degree of overlap, they also reflect the conceptual developments in HRM and the evolution of the HR function as organisations grow in size and complexity.

In very small organisations, HR duties are typically an aspect of another job, often related to finance, due to the importance of payroll. The ‘HR stuff’ is essentially transactional and carried out by relatively junior staff, in administrative rather than managerial roles. This was described as follows by one respondent:

"...it was almost a rite of passage type role. You can imagine the scenario, worked on reception, worked with customers, someone needed to look after payroll and tips, and then some other responsibilities emerged. So it was an evolution of an administration role, really."

If more complex employment relations issues arise, external advice will often be sought from consultants and/or employment lawyers.

As organisations grow, a number of different routes can be taken. In some cases, the person who has initially taken on the HR duties becomes an HR specialist, often developing through education and studying for CIPD-accredited qualifications. These functions take a ‘traditional personnel’ approach focussed on the application of policy and procedure, playing very much a servicing role with limited organisational influence.

Other small and medium-sized organisations develop what we have termed a ‘generalist progressive’ HR function characterised by significant investment in HR capacity in the form of an experienced practitioner from outside the organisation. In our sample, this appeared to be driven by the fact that owners find themselves drawn into increasingly complex people management issues as the workforce expands. This was explained by an HR practitioner who had moved from a large public sector organisation to work in a rapidly expanding and ambitious SME:

"A lead HR role was then appointed because they anticipated one, growth, and two, the fact that we would need some shoring up. Because there were some ... if I can call it casual indisciplines around things like pay awards and individuals fighting their own causes, and that going direct to the owners of the company without any intermediary to manage that in a more organised way."

The commitment to a specialist HR function represented an acknowledgement of the need for HR expertise and some increase in the prominence and influence of HR. It was notable that in SMEs that had invested in recruiting an HR specialist from the external labour market, HR was more likely to be represented within senior leadership teams.

Nonetheless, a generalist approach was usually in evidence with HR practitioners engaged in a wide variety of HR activities. Initially, the development of the HR function results in a process of formalisation as new policies are introduced and line managers seek out expert advice. This can jar against the personal and informal employment relations that tend to exist in smaller organisations, as a junior HR practitioner working for an SME who had moved from a large private sector firm explained:

"...it’s a lot more informal and a lot more flexible, whereas in the bigger organisations I’ve been used to things that are quite structured, quite process driven. And although we have those processes in place, they tend to be flexed quite a lot more, which I think is good on the one hand, but then when you’re trying to bring that formality in, you can’t give too much flexibility. That’s the challenge I’m having."

Importantly employment relations issues tend to be at the heart of HR work in such organisations but once policies and procedures are in place there is space and time to concentrate on issues such as managerial competence and employee engagement. However, while interviews pointed to clear benefits from a more holistic approach which linked employee resourcing, employment relations and learning and development, the ‘nose to tail’ nature of a small organisation HR function was not necessarily seen as a positive by HR practitioners. Even in more ‘progressive’ small organisations, further growth of the HR function was closely attached with an ambition to be more ‘strategic’:

"It’s just a very general function, whereas I know our vision is to have [Name] as more of a top level, strategic function...And we have visions that the HR department is going to grow as well."

A key element of this was a goal of greater devolution of responsibility for people management issues to line and operational managers, allowing HR practitioners the time and space to plan for the future:

"...so we are definitely more progressive HR than old school. [For] 10 years we were that tissues and issues department. We’re now around the strategic people plan."

In all the larger organisations in our sample, the ambition to be more ‘strategic’ was intertwined with greater functional specialism and the development of business partner roles. The majority of organisations followed what we have characterised as a ‘classic’ HR model. This was generally found in single centre organisations, such as NHS Trusts, schools, universities, local authorities and regionally embedded private sector organisations. Employment relations was normally provided ‘on site’ or in relatively close proximity to line managers involving some face-to-face interaction. However, there was a clear separation between this and HR business partners who carried out what were seen as more ‘strategic’ activities:

"If [a senior manager has] got a staff conflict issue they might just say to the HR business partner, actually I’ve got this problem and the HR business partner would say that the best person to speak to is me and I’ll allocate it to one of my team and they’ll get in touch to give advice. So the HR business partners don’t get involved in advising on individual conflict issues. We respect each other’s expertise, it’s quite healthy and works well."

The interviews revealed a number of different models of HR management. These are outlined in figure 3:

Figure 3 - Typical HR structures

Traditional Personnel

HR function composed of generalist HR practitioners who provide both employment relations and other advice. Focus on policy and procedure, playing a servicing role to management. Limited organisational influence.

Generalist Progressive

HR practitioners have a generalist role but greater responsibility devolved to line managers, with HR providing arms' length advice. Again found in smaller organisations.

Classic HR

HR function with a clear functional separation between employment relations advice and 'strategic' activities carried out by business partners. However employment relations is provided onsite or in relatively close proximity to line managers. Commonly found within 'single centre' organisations, such as NHS Trusts, educational establishments and local authorities and regionally embedded private sector organisations.

'Hybrid' HR

HR function with a centralised strategic core but HR business partners, whose responsibilities include employment relations, embedded within departments. As above but much less common.

'Remote' HR

Where employment relations advice is outsourced and/or provided by centralised and geographically remote advisers. Typical of multi-site organisations in the public and private sector - for example, large retail enterprises, civil service and multinational corporations.

Crucially, in most cases, employment relations work was the responsibility of HR advisers who tended to be lower in the hierarchy than their HR business partner colleagues. In some organisations advisers were led by an employment relations manager who would also deal with collective issues in unionised workplaces.

Therefore managing conflict in many organisations was associated with lower status and lower pay. Furthermore, employment relations were seen as getting in the way of HR business partners' more strategic duties. In one organisation, business partners and HR advisers had worked very closely together with both contributing to conflict management and resolution.

However, it was felt that business partners were being 'dragged into' operational issues and so the two were separated with business partners relocated to sit within operational units:

"For the HR advisers, we do all the day to day operational work... Under the previous structure, it was thought that the HR business partners were picking up quite a lot of the operational work... Under the new structure we're going to try to move away from that, so they're solely just dealing with the strategic [right] elements, and the HR advisers are dealing with all the day to day operational work and advising the managers on how to deal with any difficulties within their teams..."

In large multi-site organisations, the separation between different aspects of the HR function was even more acute with employment relations advice, and in one case, all HR activity, outsourced and/or provided by centralised and geographically remote advisers.

In some respects, this provided greater status for practitioners as the importance of legal expertise was recognised as a specialism, however this also meant that employment relations was completely disconnected from the management of HR on the ground.

A graphic illustration of this was a line manager working in part of the civil service who had never met her HR business partner:

"So there's not much of a human face to our Human Resources at all. There's nothing locally, you never see HR, don't really speak to them very much, they've shut off their phone lines; they discourage any phone contact at all. We have BPs for each department. I have spoken to ours on the telephone. He likes his emails, but I have never met him, I have no idea where he is based... There's no input to this business partner role at all, it's not a two way relationship. It's all top down, you don't get to feed much back to them."

Four larger organisations in the sample were operating a hybrid model in which HR business partners were embedded in business units but retained responsibility for providing employment relations advice at a local level. However, 3 of these were also in the process of centralising employment relations advice in 'remote' centres.

One HR business partner who had a generalist role at the time of the research explained this as the culmination of reductions in the size of the HR function:

"We've kind of shrunk and shrunk as the model's changed and we are going to shrink again, purely to go to a business partner model so... purely local business partners onsite and then there will be a service centre for all of the operational staff."

It is also important to note that, in a number of organisations, attempts to become more 'strategic' also reflected the relatively high costs associated with more traditional and interventionist models of people management:

"We were moving to that more progressive strategic HR... But... when I look back at the amount of people in the HR function then versus now we could have that luxury of being able to have long conversations with employees in rooms while they told us all their lives' problems... and they kind of liked that... but looking as to where we are now from how many members of the team we've got in the HR function, we just haven't got the time, so there was that kind of need and urgency to be as we got leaner we needed to find different ways of working."

Therefore it could be argued that the development of HR business partners and the devolution of people management to the line was, and is, driven by considerations of efficiency rather than effectiveness or concerns over strategy. Indeed, within our sample, the introduction of 'strategic' HR was not necessarily matched with greater HR influence within the organisation.

For example, in one large public sector organisation, HR, which previously had a 'seat at the top table' was now ultimately accountable to the finance department, which, according to one respondent, had 'no knowledge whatsoever of HR'.

4.2 The nature of HR work: focusing on the 'strategic stuff'

We saw in the previous section that the development of HR functions was often connected with a desire on the part of HR practitioners to be more 'strategic', epitomised in the emergence of the HR business partner role. However, our research painted a much more varied and complex picture. Practitioners in smaller organisations were generalists. This role was neatly summed up by a relatively inexperienced practitioner in a smaller organisation as "doing a bit of everything". Interestingly, generalist HR practitioners tended to play down the importance of their work.

Another, working in tourism and hospitality explained their very broad (and in many ways challenging) role as 'day to day':

"I'm more day to day, I do the payroll, the recruitment, disciplinary and grievances, the general welfare of the staff, support and guidance to heads of department, so it's much more generalist... it is really broad."

However, the senior (or sole) HR practitioner in small and medium sized organisations arguably operated at a strategic level across the full range of HR activity. Arguably these individuals were the closest that we found to the changemakers or change agents identified by Storey (1992) and Ulrich (1998).

In some respects this is not surprising as they were often brought into the organisation to deal with the HR consequences of rapid growth. They were certainly working in close partnership with senior operational managers, providing advice over resourcing and relations issues.

In almost all the large organisations in our sample, the role and significance of the business partner was extremely prominent in both discourse and practice. However, on closer inspection, this covered a wide variety of different approaches. While it is difficult to delineate between different business partner roles, these were influenced by location and organisational context to some extent (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: models of business partnering

'Generalist' business partners

In one smaller organisation the 'business partner' simply covered frontline delivery of HR support for the 'business'... this included employment relations issues. In others, generalist HR practitioners were dedicated to a specific department or area of the organisation.

'Classic' business partners

Here business partners worked onsite and were dedicated to a business area (or areas) and in some cases were embedded with the area rather than 'sitting' in HR. However, they generally did not deal with specialisms such as development or relations. Their focus was more 'strategic' in that they were concerned with providing an overview of HR issues. They would generally not get involved in operational employee relations issues, but in practice resourcing tended to dominate.

'Regional' business partners

A relatively common model was regional HR business partners covering a variety of sites and locations, usually backed up by remote specialist ER advice and in some cases on site operational HR advisers. These regional business partners would visit specific sites from time to time.

'Remote' business partners

In one case, business partners had responsibilities for particular departments but were based remotely in a shared service centre with all contact through either phone or email.

Within our sample, the HR business partner role had 2 main facets: first, HR business partners were directly linked to, and in some cases embedded within, an area of the organisation. Consequently, they were arguably in a good position to understand the business context within which HR advice and guidance is given. This should also help the development of close and trusting relationships with operational managers.

Second, most HR business partners claimed that their focus was 'strategic' rather than 'operational'. This appeared to mainly revolve around planning, resource and talent management... ensuring that the organisation had the right mix of people and skills to deliver business objectives.

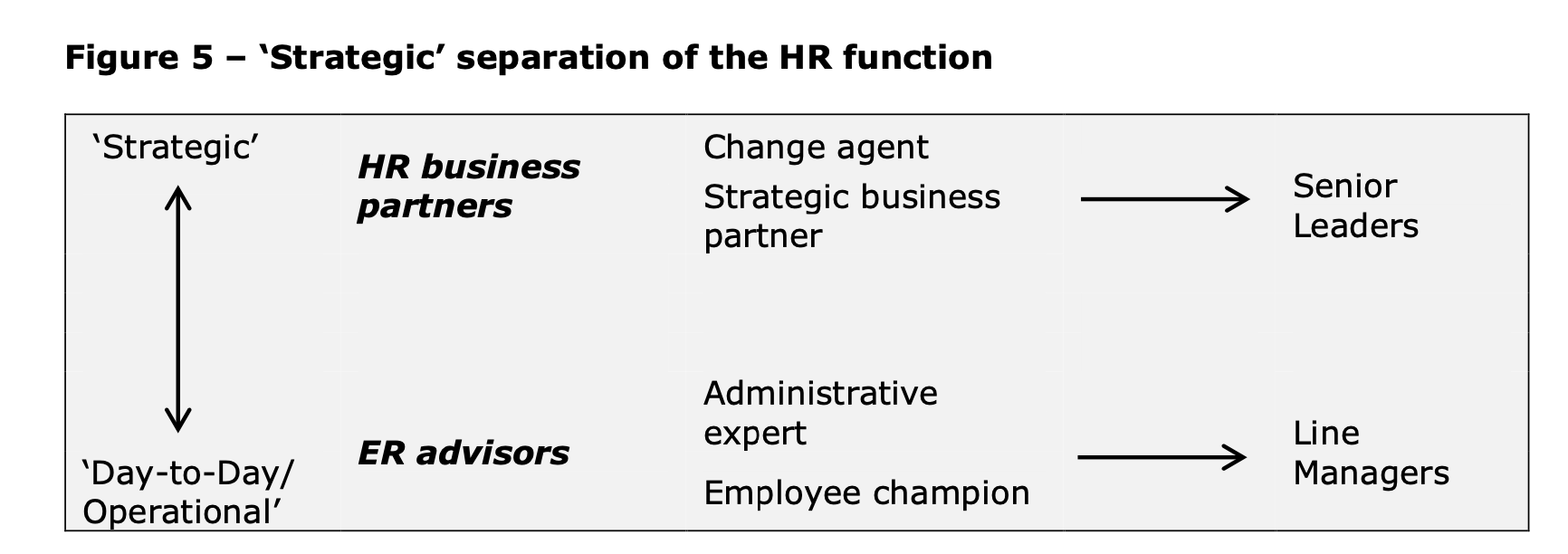

In terms of Ulrich's 4-fold typology, there was little sign that most HR business partners saw themselves as 'administrative experts' or 'employee champions' save for a concern with the systems and processes needed to engender and measure employee engagement. Furthermore, most HR business partners worked closely with senior leaders as opposed to line managers again reflecting the demarcation between 'strategic' and 'operational'.

At best, conflict management was a consequence, but not part of, strategic considerations. It therefore spun out of, and was secondary to, the overarching role of the business partner. The following quote explains the process in terms of business partners acting in a commissioning role:

"The HR business partners are the strategic commissioning individuals in HR. So let's say there was a major piece of restructure work required for the organisation. The HR business partners would get involved at the senior level, they'd understand what that restructure needs to look like and then they would commission work from our different specialist teams to carry out the restructure.

"They might commission some work from resourcing in terms of selection procedures for positions, they might commission some work from L&D in terms of retraining people for new roles and they might commission work from the ER team. So they act in that strategic space commissioning these operational services. Then there's the business as usual which we all just get along with in our specialist teams. So discipline cases, grievances, conflict, bullying and harassment and we'd deal with that as a matter of course as part of our day to day work..."

What is striking about this quote is that it echoes the language used by Ulrich in prescribing the 4 key roles of the contemporary HR practitioner. However, rather than seeing all 4 elements as equally important, a hierarchy has developed with an increasing gap between the business partner, working closely on strategic issues with senior leaders and the HR adviser providing support to line managers in carrying out their day-to-day operational duties (figure 5).

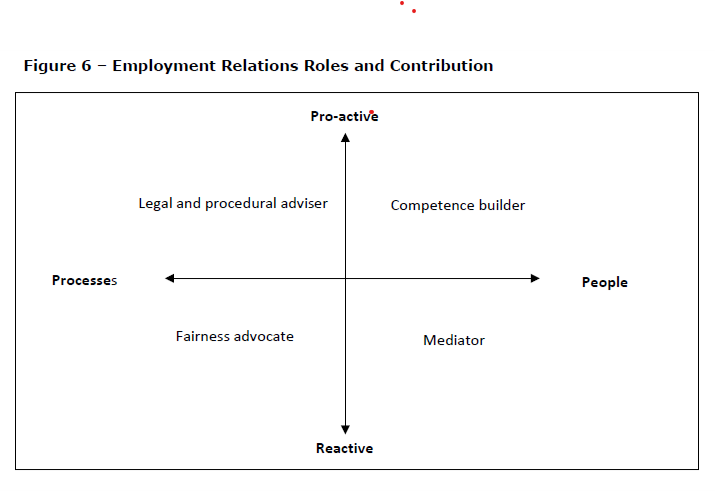

In contrast, employment relations specialists were concerned with 1 of 4 areas: informal conflict resolution; 'case work' involving discipline, grievance and dismissals; projects which had a particular employment relations focus such as TUPE transfers or restructuring; and/or collective relationships with trade unions.

The first of these areas was typically focused around policy development, procedural adherence and legal compliance. Therefore, a large component of the work of employment relations specialists was concerned with regulating line manager behaviour, as expressed in Storey's 'regulator' role 25 years ago:

"I think in some cases, ER had a profile certainly in the past of being a bit like the HR police, cleaning up after people and telling people they can't do things or telling people they should be doing things. So most stuff goes past ER, although some stuff alarmingly doesn't..."

For this respondent, 'day to day operational work' comprised of:

"Probation, performance management, grievances, if there's any grievances within the team [yeah], and also disciplinary, any disciplinary issues and the more day to day management..."

However, it is important to note that while some of these activities involved some basic transactional and administrative elements such as arrangements for investigations and hearings, note-taking and compliance-checking, they also included aspects that were proactive and which reflected both Storey and Ulrich's concepts of 'strategic'.

First, they acted as advisers providing guidance on the potential legal and employment relations implications of managerial decisions. This often (and increasingly) involved complex issues around dignity at work, health and well-being, and the application of equality legislation.

Second, employment relations specialists were vital in building managerial competences, a key element of Ulrich's idea of the strategic partner (1998:128). In some respects, this occurred through formal training in tandem with new policy development. However, and perhaps more importantly, managerial skills were also developed through informal coaching before and during the handling of difficult issues.

Third, they played a mediating role between employees, managers and, in some organisations, trade unions. This was crucial in facilitating the effective resolution of issues that might otherwise escalate with negative consequences for organisational performance.

Even in organisations whose line managers were seen as being relatively confident there was still an important role for HR to play:

"The line manager leads the conversation. We also say if you want to adjourn and just seek a bit of advice and talk it through or go I've got no idea what I'm doing then that's all alright but absolutely the line manager leads it. They make the decision. Again with coaching and conversation with us but it's absolutely line manager's decision..."

In some instances, the fact that managers wanted to check with HR was seen as a bonus as this enabled HRPs to encourage informal resolution and give managers the confidence to deal with these issues. In turn, this underpinned strong relationships and built trust with HR:

"But what's nice generally is there will be a seeking of guidance and just to double check, and then obviously at that stage some dialogue to say well, would you like support, are you happy to go ahead and do that? So therefore, it causes conversation... and we're quickly then able to encourage that nipping in the bud approach to say 'let's have the conversation, let's get it out there, let's do it in an appropriate way for our style, which is open, honest, collaborative, and improvement focused, rather than a big stick, if we can. And that seems to have manifested itself in some really strong relationships..."

Paradoxically, the handling of an employee grievance (often seen as a transactional activity) is a good illustration of the potential value-added by the work of employment relations' specialists and advisers. In a unionised organisation, an employee representative will typically contact HR to discuss the concerns of a member. The HR practitioner will explore the potential for an informal resolution, negotiating with the employee representative and in some cases playing a facilitative role and advising managers of the implications of a formal grievance.

If the issue escalates, the HR practitioner may be present at investigatory meetings and/or hearings. While nominally present to take notes, they will not only provide expert advice but also coach the manager (if necessary) through the process and review any learning after the grievance has been concluded. Of course, this is an 'ideal' scenario and dependent on the HR practitioner having the requisite skills and experience and, as we argue later in the report, it relies on close and connected relationships between HR and key stakeholders. Nonetheless, it highlights that the stereotype of employment relations activity as day-to-day, transactional and/or operational is much too simplistic.

Interestingly, despite its low organisational profile, a number of responses suggested that employment relations advice was the area of HR most valued by line managers:

"I think they see the employee relations people as their greatest source of support because they're the person who they're meeting with and coaching through these tricky, employee relations scenarios and conflict in the workplace, thinking about their own style and how they handle it and how they communicate..."

4.3 Practitioner perspectives: the importance of fairness

Despite evidence of the value of employment relations activities and particularly that related to managing conflict, the majority of respondents perceived this as transactional. Even some employment relations specialists saw their work as 'business as usual' and as a lower order of importance than that done by business partners. In this context, employment relations was less attractive to newer HR practitioners and managing conflict in particular was seen as counter-aspirational. In most organisations career progression was associated with moving from HR advice to become a business partner and from what most practitioners perceived to be from a transactional to a strategic role.

In some respects, this also reflected the way in which most HR practitioners conceptualised conflict, which was generally linked to manifest expressions of conflict such as disciplinary issues and grievances. In particular, the link between conflict and broader issues of performance and productivity was relatively opaque and circuitous. For example, an HR practitioner in a medium sized private organisation when asked whether managing conflict was a strategic issue replied:

"I suppose it is and it isn't. It's sort of a transactional day job kind of role. It's going to be there, it's part of our role, but it's not being translated into a strategic aim. I'm more strategic about our projects and how we're trying to add to the value. And I know of course that conflict is one of the key roles in HR. But we're looking at it in other ways as well if that makes any sense?"

Conflict was at best an aspect of wider projects around change and engagement rather than being a priority in itself. Even where people management was seen as key to organisational performance, this wasn't viewed as normal or obvious but as something of a departure.

Perhaps the most often mentioned link between the work of employment relations specialists and productivity was attendance, which was viewed as affecting performance at every level (team, department, and organisation) because it causes extra workload on colleagues, leading to stress, burnout and resentment:

"They can have sites or locations where they've got absence rates of 6% or more, which for a business in their game where margins are so tight, is very, very high. And the analysis... was that actually if managers did the returns to work properly and if they really tried to nip these things in the bud and they started talking to people... then actually absence rates might come down... the driver was on attendance and that became the link to productivity..."

It was also a key performance indicator (KPI) which was clearly located as a responsibility of HR business partners and unlike more diffuse notions of conflict was relatively transparent and quantifiable. In contrast it was extremely difficult to measure the amount of time invested in, and the potential success of, measures to facilitate, early and informal resolution. In short, effective conflict management is invisible and therefore the value of HR investing time in this is hard to demonstrate. In an attempt to counter this, HR advisers in one large organisation had started to keep data on informal resolution to try to address this problem and demonstrate the value of more proactive approaches to conflict management.

Case study 1

This is a British multinational corporation, which employs nearly 60,000 people across a number of countries worldwide. It specialises in providing a broad range of support services, including the management of complex assets and infrastructure in safety contexts. Whilst it has some civil contracts, its main business is with public bodies.

The HR function in one large division of this organisation (employing c. 5500 employees) is undergoing significant changes, with a proposed move from a more traditional personnel management structure with generalist HR roles, to an Ulrich-type three legged model. This change is not yet complete, but there are already centres of HR expertise and some business partner roles in place. The creation of a large HR shared service centre to centralise 'transactional' HR support is in the planning stage.

Conflict is largely considered to be manifested through discipline and grievance cases, and these issues are dealt with by HR generalists or business partners. Although there are mnufacturing/industrial areas of the organisation where the employee relations climate is considered to be problematic, union negotiations and more significant 'strategic' ER issues such as these are separated from day-to-day HR management and what is considered to be the strategic people management agenda.

Instead they are 'owned' by a specific ER manager who works with relatively little integration into the wider HR team; other members of the HR team tend to consider this a very specialist function requiring a unique skill set. The activities and identities of those working in these HR 'silos' are demarcated by relatively impermeable boundaries.

Most respondents argued that the law and legal compliance more generally was not a significant consideration in their approach to conflict. Instead the law simply provided a degree of 'background noise'. However, wider considerations of 'risk' were important and in minimising risk:

"We have a few relatively new managers who will come in and it takes them a little while to understand the processes that we have in place. So they'll go about disciplinary in their own way not realising that they need to contact us first and follow a process. So it's really about achieving consistency in HR processes across the board really."

However, for many respondents, consistency was a vital element in ensuring fairness and therefore organisational justice. Moreover, this was seen as a fundamental part of the role and identity of HR practitioners.

"Well that's why you do HR, you care about people and you care about fairness and equality, you don't go into HR for any other reason"

"I know there is the legal and compliance side of it, but that almost comes second to me personally. Because I want to promote fairness for fairness, so that people feel that they are being treated equally. Because I don't want the unfair and unequal treatment to have a knock on effect for the rest of the team."

In this way it could be argued that HR had an opportunity to go beyond being the keeper of procedures and instead be relied upon as 'advocates' for doing things in a fair and proportionate way. The Head of HR in a medium-sized organisation who led a generalist HR team explained this as follows:

"They do look to me and us as the advocates for doing the right thing in the right way. We are acknowledged, I believe... as a group of people who can be flexible and come up with the right solutions in managing difficult situations and making sure that we don't always default to formality or procedure without really carefully exploring other opportunities first."

This suggests a less transactional and more creative role through which more relational and discursive approaches to resolving difficult issues are encouraged and facilitated by HR practitioners. Furthermore, as the following quote suggests, the way in which difficult issues are handled is not simply based on procedural compliance but shapes and reflects the culture of the organisation:

"You're there for checks and balances, for not just procedural stuff for the company, but actually to make sure that that individual was fairly treated as the, I guess, ambassador of the cultural standard of the company. So I think we've found a right balance where obviously that age old dilemma of where does HR really sit in terms of pro-organisational, pro-employee, I believe that we actually have a culture of legitimate objectivity and fairness, I think, and I feel very comfortable in challenging stuff that I don't think is right for our style."

4.4 Implications for conflict management

4.4.1 The marginalisation of employment relations

In the previous section (4.3 'Practitioner perspectives: the importance of fairness') we explained that employment relations was characterised by respondents as day to day, transactional and outside the remit of strategic HR. As a result, it appeared that it had become progressively marginalised and was not seen as an area in which many practitioners wanted to specialise, or even become involved.

Consequently, there was evidence of a shortage of HR professionals with employment relations expertise and experience:

"Actually getting somebody with really good, broad experience in dealing with these sorts of issues, they're rare people... People who deal with trade unions today are very rare."

This not only threatens to erode the skills base but by concentrating expertise in specific areas of the organisation, the ability to respond to conflict in an agile way is potentially eroded. For example, one respondent explained that a difficult grievance situation, 'would go to a regional manager, or it would go to a site manager, or it would come to a business partner' but this would then be quickly passed on to centralised ER staff:

"So the expertise was very much firmly within one location in [location], but consequently the rest of the HR community weren't developing that expertise. So the problem was the rest of the HR community rather than ER... Not because, I think they were passing the buck because HR haven't got the technical expertise in ER... my view was, was that increasingly ER was cleaning up HR's crap."

There was a particular problem finding HR practitioners with knowledge of trade unions and collective employment relations. Even in unionised organisations, where such expertise was seen as necessary, it still lay outside the mainstream concerns of strategic HR:

"We do have one individual who, can't remember what the job title is, but he liaises with the unions... we wouldn't have somebody who would liaise with the individuals or line managers in terms of employee relations... but at some point if there was a big restructure or something, we do have an employee relations person who will be helping liaise with the trade unions and that type of thing..."

Responses also suggested that gender was a complicating factor. This was compounded in some highly unionised environments by a dominance of (often older) male union representatives. This acted as a disincentive to new (mainly women) HR practitioners going into employment relations and also made the development of high-trust relationships extremely challenging. This in turn meant that the understanding of collective issues among HR practitioners was often limited:

"These guys have been union reps for like 20/30 years and they've seen [HR practitioners] come and go. They are quite sharp people and [HR practitioners] just don't manage them very well, really..."

This respondent argued that in his experience there was a frustration among younger HR practitioners that union representatives 'won't do as they're told', while union representatives saw HR practitioners as inexperienced and naive.

There were similar problems between women HR practitioners and older male line managers. A number of respondents referred to being stereotyped as a 'note-taker' and to managers being reluctant to take advice from employee relations advisors:

"Sometimes my female ER advisors will give advice to a senior male Manager and then [the Manager] will call either me to check that advice is okay or my Manager to check that advice is okay... it feels like they don't wish to take advice from junior female colleagues, yeah and so sometimes they will ignore that advice and do their own thing..."

Indeed, more than one respondent discussed experiences of sexual harassment from managers and inappropriate comments about appearance which undermined their confidence and made it difficult to establish good relationships.

4.4.2 Organisational distance and resolution

There was general support for the idea that where high trust relationships existed between HR practitioners and line managers (and where there were trade union representatives) informal resolution was more likely to take place. Furthermore, trust was critical in giving HR practitioners the confidence to allow managers more autonomy and accept a greater degree of risk.

In smaller organisations, HR practitioners felt that was less of a gap between them and line managers. They believed that they were approachable and less likely to be seen as the HR 'police'. At one level this was due to the personal nature of relations:

"We like to make sure everyone knows everyone, that we stick to our roots of being that kind of family, close knit organisation... If there are any issues it can be resolved informally first. There is no difficult conversation. If you've got a problem, raise it, whether that's to do with the working relationship, whether that's because you don't understand your job role, whether you want to be doing something else, you're not being fulfilled in your job role, absolutely anything. We want that open dialogue and we try and drill that in from day one... we know we're growing and there is an underlying feeling that this organisation is becoming more corporate, we're doing everything we can not to make it feel like that."

Therefore, respondents drew implicit links between the family nature of small firm relations and the potential for informal resolution. At the same time, it was acknowledged that this becomes more difficult as organisations grow. In larger organisations, and particularly those with multiple sites, HR advice is more remote, and these relationships are inevitably more frayed. Consequently, employment relations advice and intervention is focussed primarily on procedural and legal issues. The following response from a senior HR manager looking back on his time working in a large retail organisation with a remote ER advice service illustrates the potential problem of an over-emphasis on compliance and consistency:

"[The aim was to] get an outcome that you could justify, document... to demonstrate that you've followed a fair procedure... before even drawing your own conclusion you probably had to escalate your scenario to a group level role, and then they would advocate that you spoke to an in house helpline... everything was just kind of governed around process, justifications, methodology... but... if you get too geared up around process, methodology, formality and coming to a sound procedural conclusion, I think you lose something then in terms of taking the merits of the situation at face value and maintaining a sense of proportion that helps you make great decisions."

Of course, consistency is much more difficult to achieve in larger organisations. However, it could also be argued that HR practitioners will be more successful in encouraging early and informal approaches to conflict resolution where there are close relationships with line managers and perhaps where they retain a pro-active role.

While there was general support among respondents for informal resolution, and this was routinely built into policy and procedures, the increasing distance between the line and employment relations advice meant that HR practitioners and employment relations specialists, in particular, tended to get involved if an issue was headed towards formal processes.

Essentially HR would often only become involved, and hear about a problem at a relatively late stage, after the problem had escalated. Therefore, opportunities for informal resolution were frequently missed. In a large private sector organisation, telephone calls came in to what was in effect a helpline, with issues escalated to employment relations specialists largely based on the potential legal risk:

"I guess there's probably 20 or 30 people working in employment relations. So you've got a core group of what they call people advisors, which are essentially a helpline. So loads of people from all over the country ring this helpline... So if a call comes into those people though, the advisors, they will either advise, or they will escalate. So there was a group of specialists... who had quite detailed knowledge of employment legislation and that type of thing. And that would be where an EC claim would go into an advisor and they would immediately escalate it to a specialist."

In addition, as pointed out above, where employment relations and HR are separated there is a degree of role conflict, whereby HR business partners are often involved at an early stage, but tend to focus on what they to perceive to be core strategic issues. Employment relations issues would then be referred downward so by the time the matter comes to the attention of an employment relations specialist, informal resolution is more difficult. Some respondents felt that more generalist HR business partners would be more effective in encouraging informal resolution at the earliest possible stage:

"I feel an HR all-rounder is much better. I think HR would be worth its weight in gold if it could work more closely with LMs about managing conflict every day. Often they don't want to be managers but a close relationship with HR can give them that confidence to just have the difficult conversation with their team. The amount of times I am sat with a manager asking them whether they have had that conversation yet?"

In one organisation, the number of HR practitioners (on site) was in the process of being reduced with employment relations advice being centralised in an off-site call centre. There was concern that the emphasis on having good conversations at an early point could be eroded. Furthermore it was argued that having a good knowledge of the workplace and the staff involved resulted in common-sense and more 'rounded' decision-making. One of the senior HR practitioners had previously provided HR advice to a geographically disparate group of workers.

She explained how this made it much more difficult to build high-trust relationships:

"You don't just get the passing in the corridor at the coffee machine kind of moments so it's doable and I really enjoyed it but I found it really hard work from my side making the time to make the connections, all of the time. You kind of had to schedule in I'll just ring so and so for a five minute whereas you would just get that naturally. Having flipped roles it's so much easier... just having those day to day interactions and you have lunch with somebody and they tell you about their new hedge trimmer that they've got and, you know, just really mundane stuff but it helps build that relationship which you have to force if you're remote... an old boss used to say to me, HR is a contact sport and it resonates all the time with me in terms of it's the relationships, the conversations, the trust, the can I just bounce some ideas around with you, which sometimes rescues a situation. You can kind of nip stuff in the bud..."

In another organisation, HR advisors, who dealt with most employment relations issues, were attached to specific units. This proximity to line managers was advantageous when dealing with difficult issues and in building the legitimacy of HR advice:

'We're based out in the schools and colleges, but we're managed centrally by HR... And I think probably the relationships I've built with the managers and senior staff, I think that's really helpful, because I do have really strong relationship with the line managers, and senior management, so I think that really helps as well, so, will actually listen to what I'm saying."

However, while face-to-face HR is important in relationship building these findings suggest that HR being 'on-site' is not necessarily enough... in one organisation, while there were local HR practitioners, they lacked power and influence, and dealt with low level issues.

There was very little local informal resolution, unless local managers happened to be pro-active.

In most complex situations, local HR managers deferred to business partners and/or centralised specialist employment relations staff.

4.4.3 Managerial competence and control?

The classic HR model that we found in most of the organisations in our sample implied a 3 phase process of conflict management: first, line managers have responsibility for identifying, addressing and resolving issues at an early point; second HR business partners take on a strategic planning role, focusing largely on resourcing issues and talent management; third, employment relations provides a 'back-office' function, acting as an expert of last resort, if and when, conflict escalates and providing advice commissioned by HR business partners. In one organisation, this was described as follows:

"Employees then go to their line manager over the people issues so the HR piece is around kind of creating long term people plans, around the capability of the business, around succession planning, talent management, manpower planning."

The success of such an approach ultimately depends on managers having the confidence, capability and, importantly, the time to manage people and resolve conflict. However, it was clear that the research lent further weight to previous studies that have identified the lack of confidence of line managers in handling conflict and the priority given to production imperatives over people-related issues:

"It's clear that some managers are not skilled enough to manage effectively and this causes a number of issues, including more conflict."

"I would say there were an awful lot of line managers within the organisation who are not used to line managing. Some of them won't see it as their role, and some of the line managers... quite a lot of the line managers will need quite a lot of hand holding to talk them through what they're meant to be doing in a certain situation."

Managers were prone to either avoid difficult issues or fall back on process. This meant that often HR was forced to adopt more reactive positions to conflict. Furthermore, there was a view in some organisations within the sample that line managers were reluctant to address performance related issues because they feared this would lead to resistance and recriminations:

"The adversarial nature of the kind of grievances we get makes LMs nervous of managing somebody's attendance, managing somebody's performance, managing somebody's conduct because what we have is, let's say we've got an employee in post who for ten years has been coming in at half ten in the morning and the old manager never did anything. We do a restructure, new line manager starts managing that person that person doesn't like it, they want to go back to how the old line manager did it, and they put a grievance in against the new line manager."

Case study 2

This is a post 1992 modern public university based predominantly in one city in England where the main campus is located, but the university has campuses and affiliated colleges all over a larger local region. It is a large university with approximately 3000 employees.

The primary decision-making body is a senior management (SMT) team led by the Vice Chancellor. Until a recent re-structure, the most senior HR professional (the Chief Talent Officer CTO) sat on the SMT with a significant amount of influence over university strategy. Now the re-named HR Director only attends for timed business and reports to the VC via one of the permanent 'line' (non-HR) members of the SMT.

The HR department is based on two legs of the Ulrich model, with a number of HR business partners who liaise closely with their linked departments or faculties and several HR specialists (covering employee relations, resourcing, OD, training and wellbeing).

All are based in a building on the main university campus, although HR business partners are co-located within specific departments. Conflict is seen largely as formal expressions of discipline and grievance issues, and line managers are expected to handle these problems at the early stages with support from the employee relations specialist team rather than business partners.

HR business partners work most closely with senior managers and focus on planning, resourcing and talent management. Line managers who need advice and support over potential workplace conflict are normally directed to the employee relations team. Line managers vary in their ability and confidence to handle conflict in their teams, and a degree of close 'hand-holding' is evident, with the ER specialists largely driving the resolution processes.

Issues around the management of performance and setting clear goals and expectations for employees highlighted some of the difficulties associated with line managers' attempts to manage conflict:

"Performance management's quite a big one... some people will have their own way of doing things and they'll eventually come to us and say oh, you know, I've spoken to this employee, they've done it multiple times, they're still not listening to me, can we get rid of them. And you just think well, hang on, I've just looked in their file and there's no paper trail... A lot of conflict does come from people who perhaps haven't been given the constructive feedback that they need or they haven't had the appraisals that they need to show what they need to develop on.

This lack of confidence and capability meant that in the majority of organisations in our sample, HR practitioners were not able to 'let go'. In a number of organisations, there was evidence of informal processes being formalised and the widespread use of management tools... such as checklists, flowcharts, and templates. In some respects, while HR practitioners and especially HR business partners have rejected their role in 'hand-holding' of line managers, this has been replaced by longer 'reins'. Ironically, as HR became more distant from the line, the reliance on formal process and procedure has become more and not less important.

Although it could be argued that the regulation of line manager activity is both disempowering and also limits the potential for more creative approaches to conflict resolution, a number of respondents also argued that real devolution was unrealistic given the expectations and pressures placed on some line managers. In particular, HR practitioners in the NHS argued that ward managers, staff nurses and others simply did not have enough time either to resolve issues informally or take full responsibility for the formal aspects of conflict management. Similarly, in another public sector organisation, managers in a highly pressurised area were expected to conduct fortnightly one to one chats with their team members to manage performance and prevent conflict developing.